Here's What's Missing in the Debate Over Central Park's Horses and Carriages

Should the horses and carriages of New York's Central Park be banished? The proposal, initially floated by the city's new mayor, Bill de Blasio, as a campaign promise, has set off a firestorm. The mayor reiterated his position in a recent Associated Press article saying, "it's inhumane," adding, "Horses working on the streets of New York City ... it's not right. We should change it." According to the article, "People for Ethical Treatment of Animals launched an antihorse carriage campaign with celebrities ... including Alec Baldwin, Pink and Lea Michele." Mayor de Blasio's opponents, who argue the horses and carriages have been iconic park fixtures since at least the 1880s, include members of the City Council, actor Liam Neeson, the New York Daily News, which is promoting a "Save our Horses" campaign, and the New York Times editorial board, which wrote: "Let the carriages and the horses alone." The New Yorker also weighed in with a witty cart before the horses-themed cover.

The horses and carriages, state-of-the-art conveyances in the 19th century, today largely cater to tourists, and ending that trade would have consequences. According to the Wall Street Journal a ban in New York would impact 300 to 400 jobs, which has drawn the ire of some unions. And, this is not just a New York story, efforts are underway in other cities to curtail or eliminate horses and buggies, which would affect some 1,200 operators nationally.

However, since this has been positioned as tradition and nostalgia vs. animal welfare/rights, what about the horses? Holly Cheever, a veterinarian and vice president of the New York State Humane Society wrote in the New York Times: "I've examined New York City carriage horses, and reviewed the work of others, and I have found that the city's population, infrastructure, climate and vehicular traffic volume create inhumane conditions for these animals." Ms. Cheever cites an unpublished study conducted in 1985 and "photographs that show that New York City horses often lack the essential provisions for appropriate stabling ..." before concluding "the horses' welfare is endangered both at work and at rest, and this tourist attraction should cease."

By contrast, Dr. Mark Jordan, in the New York Daily News, was a bit more empirical and wrote: "As the head of an equine veterinary practice in Carmel, Putnam County, I have been examining and treating horses for more than 32 years. I felt it was my responsibility to investigate the horses' treatment from my own perspective as a veterinarian, horseman and advocate of animal rights." He added that prior to visiting the park and its stables he was "skeptical of the care that these horses were receiving." After examinations conducted during scheduled and unannounced visits, he stated, "Contrary to what many may believe about these horses and the environment that they live in, the horses are in good health and are living in an appropriate stable with excellent care." Moreover, "the horses were housed in comfortable, clean, spacious box stalls, which allowed them to lie down in comfortable dry bedding." He concluded, "These horses are being loved and cared for earnestly and deserve the right to continue on as a historic tradition of the city."

The presence of carriages is more than a nostalgic touch. In Seeing Central Park, author Sara Cedar Miller wrote, "Before Central Park was created, there were few opportunities in the city to ride through natural scenery either in a horse-drawn carriage or on horseback. The streets of New York were chaotic." A recent Wall Street Journal story quoted Thomas Kinney, "an associate professor of history at Bluefield College in Virginia who wrote a book about the horse-drawn carriage trade [as saying,] 'Central Park was created as a venue for the carriages ... It was a chance for people living in crowded urban areas to go for a drive in the country without leaving New York.'"

The park's famous landscape architects, Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. and Calvert Vaux, designed the park to be viewed from carriage and horseback, as well as on foot. And the scenery included the park's visitors - New York has always been great for people watching - which they accommodated by putting footpaths adjacent to carriageways. As they wrote in the Greensward Plan of 1858 (also known as the "Description of a Plan for the Improvement of Central Park"): "[I]t is hardly thought that any plan would be popular in New York, that would not allow a continuous promenade along the line of the drives, so that pedestrians have ample opportunity to look at the equipages and their inmates."

The curvilinear roadways are also deliberate, as noted in the Greensward Plan: "The popular idea of the park is a beautiful open space, in which quiet drives, rides and strolls may be had. This cannot be preserved if a race-course, or a road that can readily be used as a race-course, is made one of its leading attractions."

In addition, the carriages animate the landscape, something to which Olmsted paid great attention in the many projects he designed. For example, as recounted in Devil in the White City, by the end of 1891, in the design for the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the question of what kind of boats to allow on the fair's waterways had come to obsess Olmsted, "as if boats alone would determine the success of his quest for 'poetic mystery.'" In response to a proposal by a tugboat manufacturer, Olmsted complained that it "framed the boat question solely in terms of moving the greatest number of passengers between different points in the expedition as cheaply and quickly as possible." Olmsted's intent was that "mere transportation was never the goal" and "the whole point was to have boats enhance the landscape."

The authenticity of the park experience incorporates the material elements, including the careful orchestration of trees, rock outcroppings, bridges, meadows, paths, roadways, ponds, and other features; and the experiential, among them the sights and sounds (and smells) of the carriages. Their measured gait slows down traffic and also slows down our eye, allowing for a more leisurely viewing of the surrounding landscape. The horses' rhythmic "clip-clop" functions like a metronome in gently guiding this steady progression.

What Central Park does face, however, especially the southern portion is congestion. Cars, carriages, bicycles, pedestrians, skateboarders, in-line skaters and others compete for space.

And, in recent years there has been an onslaught of pedicabs, though they are now being regulated.

Just wait until we have to deal with personal drones.

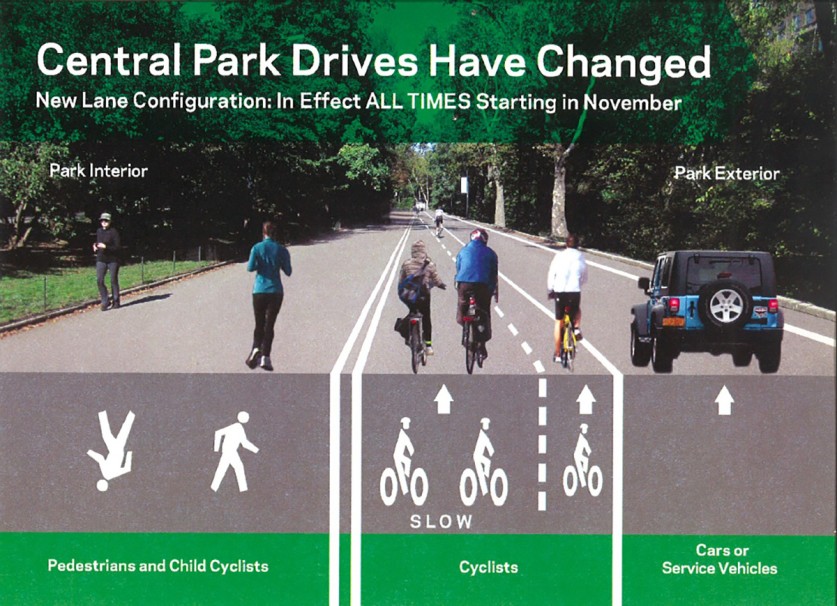

To deal with all this traffic, in October 2012, lanes for the various users were redrawn, to the benefit of bikers and pedestrians, but to the detriment of cars and carriages, which now have less room.

Management of the park, as I've previously written, is a challenging and expensive endeavor - and integral to that is material and experiential authenticity. Whether the horses and carriages stay or go, this increased congestion will have to be addressed - it's a matter of public safety and the park's authenticity.

This blog first appeared on the Huffington Post Web site on April 30, 2014.