It Takes One: Dale Skinner

I was raised on the Hearst Ranch in San Simeon where my Dad trained and bred horses. He was superb at his work and taught me to take on the trade with his same attitudes of care and patience. The place was wild and beautiful, and I spent all of my time outdoors. Even as a youngster, I knew this milieu was where I belonged; but I also realized that the landscape around me was changing. In my late teens, I began taking photographs that documented ranch life and our work with horses.

Later, I trained horses on my own and worked in rural areas of the Santa Ynez Valley and the Santa Monica Mountains. In 2008 I took over the planning, design, and maintenance of approximately 400 miles of trails in the Angeles District as Trails Coordinator for California Department of Parks and Recreation.

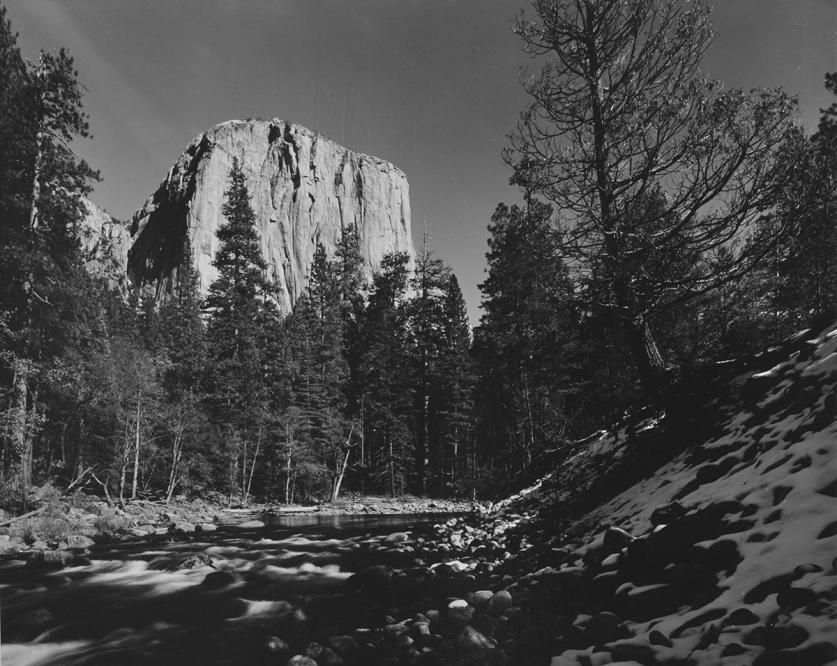

During those early years, I experimented extensively with black-and-white film and composition. The main purpose behind my photographs then was to record a disappearing landscape and way of life. As I matured, my documentarian focus remained undiminished, but I also found myself seeking ways to visually tell the not-immediately apparent stories that informed my subject choices.

How would you define a cultural landscape?

I see all landscape as cultural today. This is not just because most landscape is touched by some level of human visitation or intervention. It also has to do with how we employ technological and visual tools to understand our landscape. Cultural landscapes reveal to us stories of intention, circumstance, and serendipity with respect to the land. The stories behind these changes fascinate me.

How is your creative process influenced by the landscape?

I tend to be somewhat introspective, and my trail work in the natural areas of public parkland during this last decade has often been solitary. These factors prompt me to seek out the stories within our natural landscape as a way of understanding my personal values and the values of those around me. Because of my work, I now find that I also bring a perspective of protection to my photographic point of view. This perspective has been sharpened through my discovery and purchase of a large cache of vintage photographic equipment in 2011, including a Deardorff 8"x10" view camera, the same model used by Ansel Adams in many of his iconic Yosemite photographs. When acquired, much of this equipment was in disrepair and required the utmost patience and precision to repair. Over the several years it took to make these repairs, I found that the process itself informed my understanding of cultural landscapes; later, as my photography field-trips led me to some of the most scenic parts of California, I comprehended that the tools we use to understand the landscape are also part of the cultural landscape's story. And this sense is even sharper because of Adams' own perspective. I feel a kinship and sense of responsibility to honor his efforts, and to show respect for the landscape images of the past that were captured with these same vintage cameras and lenses.

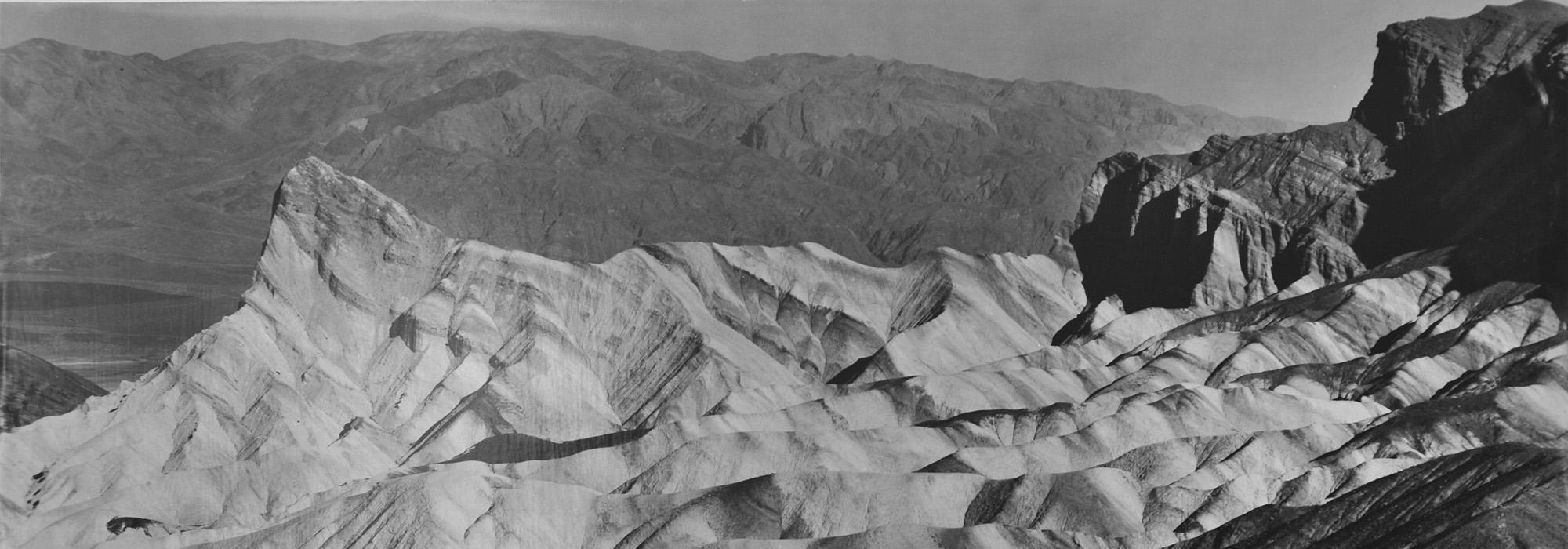

Can you tell us about your work in Death Valley?

Racetrack Playa at Death Valley National Park is populated with "sailing stones," rocks that mysteriously move along the occasionally wet mudflats, leaving trails as long as 1,500 feet. How did they get there? Why and how do they move? What are the puzzling indentations in the dried-out mudflats nearby? I had these questions and more, and subsequently learned that National Park Service scientists recently discovered that the rocks move when winter ice sheets, only a few millimeters thick, begin to thaw on sunny days. As the ice sheets break up, wind shoves the rocks along at up to five meters per minute. The fact that this phenomenon occurs naturally in an undisturbed environment tells us, first, that the site has been protected. But careful examination of my photographs of the area also reveals the presence of rogue footprints and missing stones, telltale evidence of human curiosity and greed. My photographs tell a story of nostalgia and juxtapose our reverence for the untouched landscape with an acknowledgment of the human impulse.

How did your understanding of the landscape at Death Valley change as a result of your work?

Significant natural landscapes are disappearing, and not just the great ones. It is becoming increasingly rare to see protected natural landscapes without, for example, phone lines or cell towers. Even a natural sky is hard to photograph; I sometimes wait hours for jet trails to disappear. In some respects, it is even more difficult to preserve cultural landscapes because they are subject to more development pressures, which, I think, is exacerbated by an inherent tolerance for change once a landscape has evolved to show use. People often have a hard time deciding just which changes are acceptable and which changes are not. In the end, photographs may be the only way to preserve the landscape as it evolves.