It Takes One: Hazel White

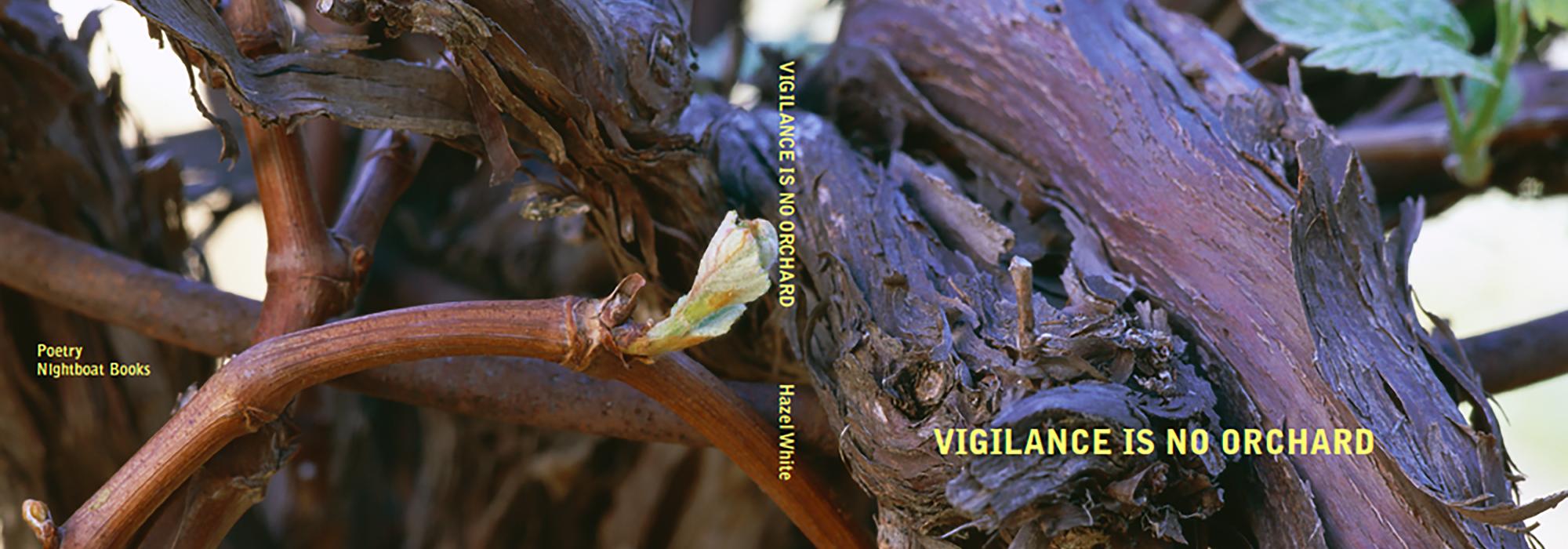

I am a writer. I grew up on farms in England. I have an undergraduate degree in philosophy and an MFA in writing. I have written books on garden design published by Chronicle Books and articles on landscape architecture projects for the London Sunday Telegraph Magazine and Hauser, etc. Now I am a poet, still writing about landscape, but the writing appears in different spaces—literary journals and books, museum exhibitions, interdisciplinary conference panels. I miss conversations with landscape practitioners and theorists and have enjoyed responding to the questions here about my most recent book, Vigilance Is No Orchard. I wrote it in response to a work of landscape architecture: the garden Isabelle Greene designed in 1982 for Carol Valentine, internationally known as the Valentine Garden. I hope very much that my time researching the experience of space and developing a dense and particular mode of expression (both of these necessary to my writing about Greene’s extraordinary garden) has enriched my understanding of landscape.

What does the Valentine Garden mean to you?

I think of the Valentine Garden now as a kind of superaddition to reality. The making of it was a formidable challenge for Greene. She could not bear that tall white walls separated the garden from the oak and bay woodland beyond it. And she had to work with the geometry of the walls. She hates geometry. Instead of complying with it, she eventually found her way to defy it. The terraces in the image I first saw, viewed from the house above, read like miles of California landscape viewed from a plane, the geometric forms of agriculture interrupted by the organic lines of creeks and foothills. She gently and purposefully blew the space open; there is absolutely no sense of containment within walls. Greene’s garden presented me with a similar career challenge. It wasn’t easily read. I was a freelance writer and although I wrote about the garden several times for magazines and a museum catalog, I wasn’t satisfied with my writing. I wanted to write something that would make the reader superalert, the way the garden had affected me. So, I learned how to write poetry. When I visit the garden now, I think of Carol Valentine, Isabelle, and myself, and our very active devotion to that place.

How has your understanding of landscapes, both the Valentine Garden and others, changed as a result of writing your book?

I turned to artists’ writings, philosophy books, and even a classic bodywork text to understand more about how humans experience the pleasures of space. I’m not so much interested in the objects of contemporary desire—native grasses, organic gardens, etc.—as in what animates us in landscape, what becomes open to us in certain spaces, what sets us into motion. And Isabelle’s work raised the question: What will we make if we can build space, or text, exactly the way we want it? I listen for expansive answers. A cultural landscape/experimental prose of possibility, becoming?

Have other people’s understanding changed as well? If so how?

I am absolutely sure from the reception of my work that people are fascinated by landscape and their relationship to it. I think my success as a poet is very bound up in my knowledge of landscape; people enter the work through their interest in what I am saying about it. Usually, it’s a new way of thinking for people. I believe landscape architecture could have a much larger role in public discourse.

In the book, you often speak about losing yourself one moment and then finding yourself again in another. The garden seems to be a collection of perspectives that offers its visitors choices. Upon revisiting the garden, have you found that your own opinions and perspectives have changed?

Yes, that’s right. For many years I was feverishly exploring one perspective or another. Then Carol Valentine passed away, and the property was sold, and for unknown reasons the garden was neglected. The last part of the book addresses loss. When I read from it, people become very attached to the garden, wanting to save it. If I were to write my way out of Vigilance Is No Orchard into a new work, it would concern loss. Rebecca Solnit’s statement “Landscape’s most crucial condition is considered to be space, but its deepest theme is time,” has always been on my mind. And Tacita Dean’s final pronouncement about place, after a long study of it with Jeremy Millar: Place “can only ever be personal . . . will always connect to somewhere in our autobiographies.”

Greene often manipulates scale and form in the garden to create different perspectives; there are tall wooden arbors, waist-high shrubs, and short flowers and groundcover on the descending earthen terraces. It’s like a city complete with noisy high-rises and suburbs surrounded by quiet-contemplative fields. Is the Valentine Garden a microcosm of the human experience of living in the modern world?

Lovely question. Or is the Valentine Garden a return to a primordial experience of habitat? Or a lively integration of both? Plus, a promise of a state of being—to be so alert and porous to beauty and nonhuman life? That quality of alertness is what Isabelle and I agreed one day was the experience of paradise. Myself, I would put the emphasis on the ground plane and how carefully it is worked, no volumes—only airy and soft-colored shrubs, only one arbor and that a very open one. A modern world made spacious, inviting, and brilliant in its conveyance of care and assurance that the maker has thought about you.

To give your readers moments of analysis and reorientation, you seem to have borrowed the tactic Greene used in the garden. She drew from the zigzagging filigree of desert plants to create areas of scrutiny and contemplation. Is your book the literary companion to the garden’s architectural plan?

It may be that, yes. I imagine as Isabelle drew by hand the plans for the Valentine Garden, pieces of which are reproduced in the book, that she was thinking, I want the path to go this way, and oh, that would be fun, to have the horizontal branching of the espaliered white bauhinia playing against the horizontal line of the top of the white wall. I imagine her laboring to make the design sound and throwing in some animating “clues” like the parallel white layers, which she explained to me that only some people would recognize but everyone would feel. Likewise, I built a foundation of sense—pieces of landscape theory, descriptions of place, sections named as refuge or view—and then in other places worked language into a vortex of experience. There are many quotes from Isabelle in the book. I’m remembering one about space-making that seems to relate to this matter of distinct moments: “Low where I want you to feel welcome, and then high to cradle you.”

What is the message that you would like to give our readers that may inspire them to make a difference?

Philosopher Alva Noë believes human consciousness does not reside in our heads but is something we do—in the present in response to the world, which shows up for it. Plato believed that nothing deserved to be called beautiful unless it compelled the viewer to care for it or others. What does a landscape look like that encourages a visitor to step out into the world, alert and superalive, and ready to care more about something?