It Takes One - Janice Ross

Janice Ross is an author and Professor Emerita in the Department of Theatre and Performance Studies at Stanford University. She writes on contemporary dance in relation to cultural politics. Her publications include, Like A Bomb Going Off: Leonid Yakobson and Ballet as Resistance in Soviet Russia (2015) and Anna Halprin: Experience as Dance (2007), a comprehensive biography about of the choreographer. Ross’ most recent publication, The Choreography of Environments: How the Anna and Lawrence Halprin Home Transformed Contemporary Dance and Urban Design, explores connections between dance and landscape architecture, and is available for purchase in both paperback and hardcover.

As The Choreography of Environments is about both Anna and Larry Halprin, can you describe how their creative and reciprocal relationship worked? Are there lessons learned that can translate to creative marriages today?

Let me begin my response by listing four words: Stairs. Decks. Chairs. Windows.

I am not dodging the question. These four objects for me seriously mark the starting point for discovering how Anna and Larry Halprins’ art and marriage cohabitated in a reciprocally beneficial way. Their relationship as artists and marriage partners was complex and filled with the rich productive tensions only two major artists living together for 70 years can survive and thrive in. Fundamentally, they were both artists whose work centered around the movement of bodies through space, and these four objects shaped those bodies in significant ways.

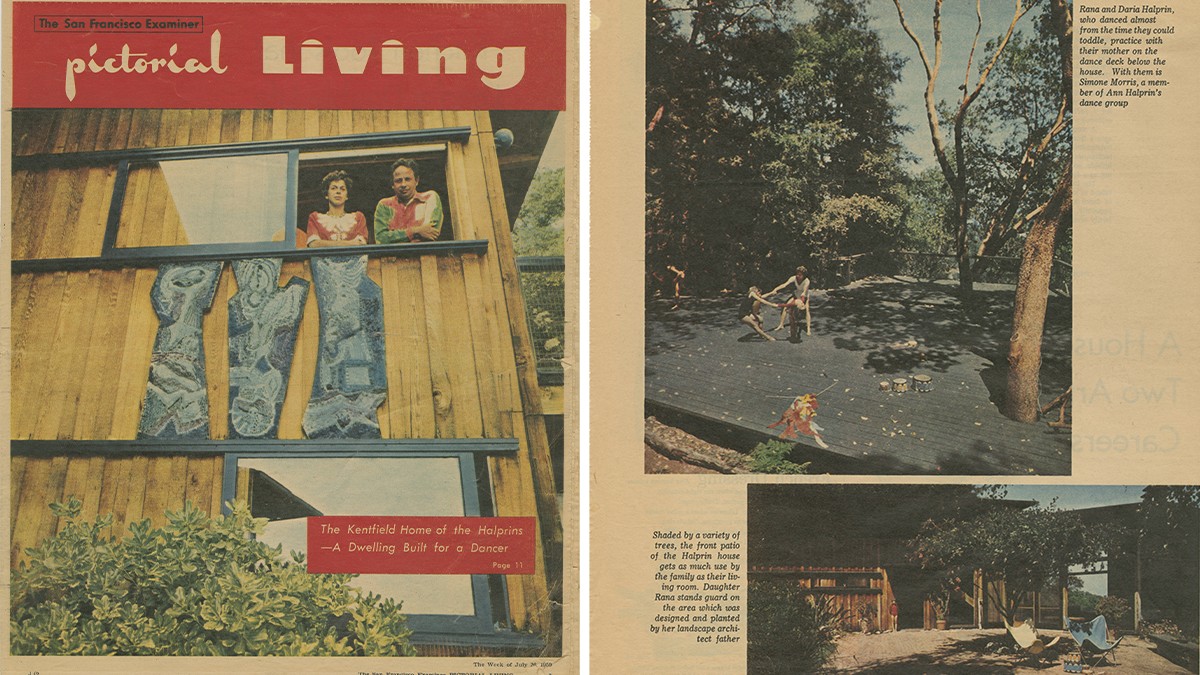

The Halprin property was always filled with the comings and goings of dancers – their bodies animated the spaces of the gardens – spaces Larry designed. Bodies trained in the aesthetics of occupying space and negotiating objects were always present on the Halprin property and often in the house, and Larry learned from watching them. Anna, in turn, absorbed lessons in the politics of Larry’s designed landscapes and how they brought her own and her dancers’ bodies into heightened awareness to how designed environments enact mini-choreographies on the bodies moving through them.

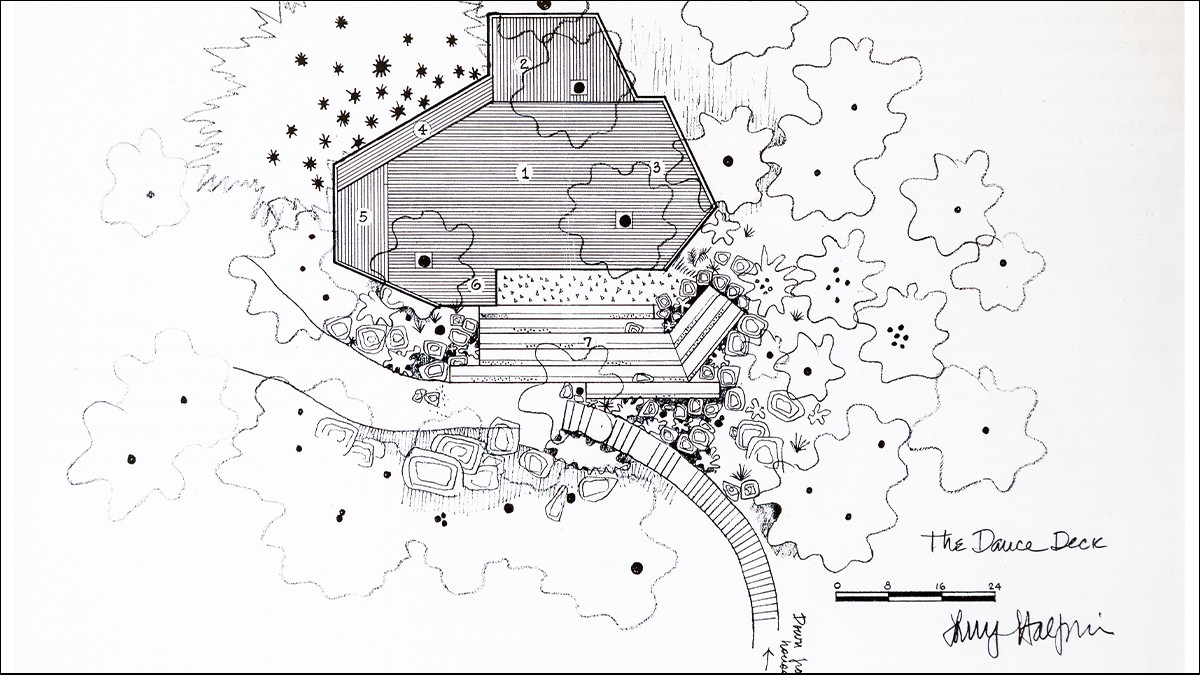

As Anna walked Larry’s stairs her body developed a certain rhythm of fall and recovery, and as Larry walked the gardens he saw dancers responding to the deck as an animate partner. This reinforced how environments impose choreography on people moving through them. Anna found how dancing on a studio in the midst of nature forced a new humility on the body and a new approach to it as an object.

I believe a significant part of their influence on each other flowed from the kinds of objects with which they surrounded themselves, the design choices they made in their daily lives as parents and marriage partners. With the exception of the groundbreaking "Experiments in the Environment" summer workshops they taught collaboratively in 1967 and 1968, they worked separately. But they each began and ended their day in the same house with its uncomfortable Modernist seating, huge walls of glass windows onto nature, and stairs and dance deck hovering just down the hill.

As for lessons for other creative marriages? Here my advice is more for those doing the looking at the marriage and art rather than living and making it. Every practical choice has the potential to be an aesthetic one. Leap and then look.

You have suggested that Larry Halprin’s observations of his wife teaching in the hillside studio and dance deck at their home in Kentfield, California, informed his notions of choreographed movement and urban design. Please explain, and if possible, cite an example or two.

Anna’s task performance approach to dance was the perfect analog to the Bauhaus embrace of craft and art as co-equal. One flowed from nature onto the deck and back out so the stage was everywhere – the approach down the stairs, the retreat to the stadium benches by its side – all designed space that both anticipated bodies and shaped their use of it. Environments are experiential as well as kinesthetic triggers – these are some of the lessons Larry absorbed from Anna and repurposed in his urban designs from Ghirardelli Square to Levi’s Plaza and the FDR Memorial and Yosemite Falls Approach. One enters these spaces with a practical objective and leaves with what the philosopher John Dewey would call “An Experience.” Almost imperceptibly they impose a choreography of the practical on one. No benches to sit on? Try this rock or granite block as you would if hiking in the woods and become part of the art rather than a passive spectator of it. Anna’s participatory theater of the 1960s where she eliminated seating for the audience and met them at the door with a choreographic score fed into how Larry viewed the implicit instructions of his urban designs. I think he also learned from Anna how sound sculpts movement, and his environments are masterful at using water acoustically.

Conversely, how did the dance deck’s setting, nestled into a grove of redwood trees, influence and/or inspire Anna’s understanding of dance as an integral part of environmental design and nature?

Anna liked to say that the deck taught her there was no center to the space, she was the center wherever she went. The deck taught her the natural harmony of differences – how dried leaves and branches littering the surface of her dance floor and the cawing of scrub jays watching from the redwoods all folded into the dance moment as elements not distractions. Working on the deck imparted to her a grounded reality of the body just being. Even in her most theatrical dances of the early 1960s, like the Three-legged Stool or Apartment Six, the dancers did not become fantastical characters, they were always on some level just abstractions of a quibbling married couple – good natured proxies perhaps for Larry and Anna.

For the Halprins what does fostering movement mean?

It’s interesting that the Germanic root of the word “foster” relates to food and means to nourish, and we can think of the Halprins each setting up the conditions of “nourishment” physically and emotionally to allow bodies to grow and flourish through an encounter with their works. In Anna’s dances it was usually a predetermined score that mandated activities with social objectives, providing guard rails around each performer. In Larry’s work the shaping of space through hardscape, landscape, the pre-designed environment of public spaces, fed the civic body, gently leading it into new ways of experiencing urban space while remembering the wildness of untamed nature.

Today we take the idea of hybrid live/work space hybrid for granted. What can we learn from the way that the Halprins made art at home, and the notion that art was part of everyday living and essential to sustaining oneself?

It’s interesting that the reason the Halprin home first became a live/work space was because of safety, but the resultant structure then morphed into a platform for aesthetic risk. One day when the two little Halprin girls were home with a babysitter and Anna was at the dance studio in San Francisco’s North Beach where she taught, she received an urgent call from a neighbor informing her that her caregiver had fallen asleep with a lit cigarette and started a fire. Soon after Larry and Anna decided the solution was to build a studio for Anna at home so she could teach, rehearse and parent. I think no one anticipated how this continual proximity of the deck to the house would change lives and art. People and ideas flowed from the house to the deck. Watching the easy play of her children became an inspiration for game-like structures Anna began to use to generate choreography. Routine household activities like bathing, eating, dressing and undressing, were revisited on the deck and rebranded as Postmodern dance. In Larry’s work the influences were more subtle, his largest works like the FDR Memorial contain “rooms,” “furniture,” and “windows,” where one moves through a succession of bounded spaces, encountering surfaces for sitting and portals for viewing the surrounding nature, just as in the Halprin home.

This last question may not be specifically addressed in the book: You note that the Kentfield home, designed by architect William Wurster with a landscape by Larry Halprin, was sold in 2022; how important is its survival as a nationally significant historic site with myriad areas of significance and influence?

Ah, this is the pivotal question! A couple of months after Anna’s death, shortly before her 101st birthday, I walked through the Halprin house and its surrounding property before it was to be listed for sale. I absorbed how the now unused furnishings and empty spaces suddenly seemed important maps, a hidden archive. This was the genesis of my book. I wish the home had been declared an historic site rather than being sold into private hands. Perhaps The Choreography of Environments can be thought of as its ghost catalogue and prompt its evolution into an important historic site.