It Takes One: John T. Reddick

I was educated at Yale University’s School of Architecture and had two amazing and influential professors there, the architectural historian Vincent Scully and the historian of African and Afro-Atlantic art Robert Farris Thompson. They were both dynamic presenters of history and culture, and their imparted wisdom greatly influenced my thinking on architecture, open space, and the impact on human engagement. In New York City I initially worked at firms focused on architectural preservation and rehabilitation. Later I joined the design office of the Prospect Park Alliance, where I was drawn into the field of landscape architecture. I followed that by working for Harlem’s Abyssinian Development Corporation, a community-based organization that was then headed by Karen Phillips, FASLA, who introduced me to work on public projects. In recent years I’ve partnered with Melissa Potter Ix, ASLA, of the landscape firm StudioHIP, on projects that have included New York’s LGBT Memorial in Hudson River Park and collaborations on public-school playgrounds and recreational park designs for the Trust for Public Land.

What prompted you to devote so much time and energy to writing and thinking about Harlem’s cultural landscapes?

I always admired Harlem’s architectural beauty, its wide boulevards, its natural landscape with such variation from the heights to the plains. Looking at the area’s natural landscape immediately reveals its original allure to the human spirit and the desire to build there. Observing Harlem through that lens has also brought me to consider the area’s landscape in partnership with its architectural streetscape, its panoramic view of Manhattan’s towering skyline, and vistas along the Hudson River. I feel this inspires Harlem residents spiritually and serves as a touchstone to Harlem’s historic position in the orbit of New York City as a cultural mecca.

Can you give us some insight into the cross-influences of Harlem’s Black and Jewish populations?

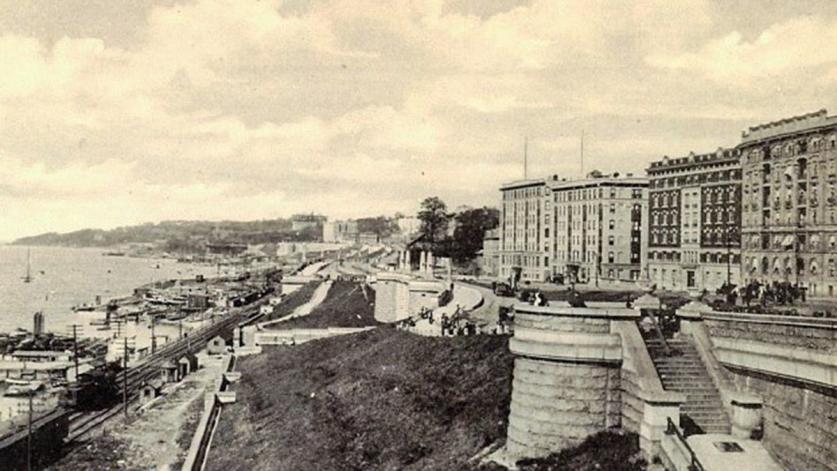

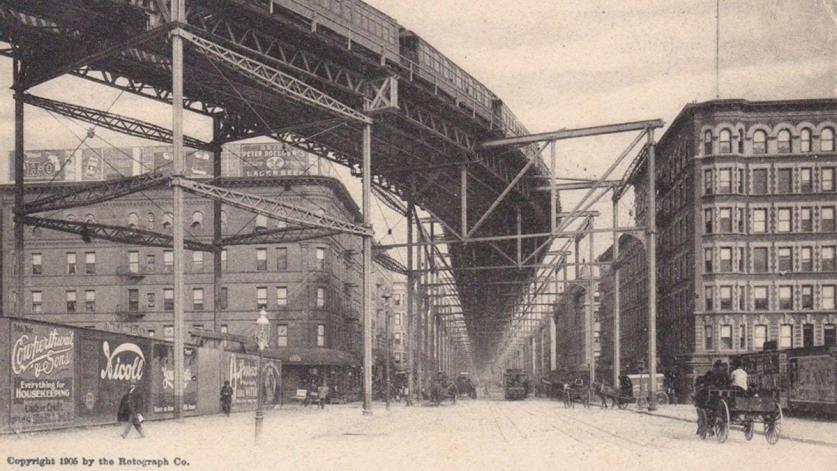

Sure. I’m working on a book that explores Harlem’s Black and Jewish music culture (1890-1930), having first stumbled on the topic while reading Jeffrey Gurock’s book When Harlem Was Jewish, in which he discusses how the Jewish tenement dwellers were being displaced by the building of the Williamsburg and Manhattan Bridges and the expanded roadway access they required. This was during the same period when African American tenement dwellers were being displaced by the building of Pennsylvania Station and its associated railway yards. Both groups followed their more well-heeled counterparts who’d already established homes and religious institutions in districts of Harlem, eventually gravitating to the poorer tenement areas along the elevated train lines of Eighth, Fourth (Park), and Third Avenues.

The young people of the tenement class and their well-to-do peers shared a love for the new music of the day—ragtime. That audience and their influence changed the direction of Harlem’s theater and musical entertainment. George Gershwin, Lorenz Hart, and Sophie Tucker would be drawn to the talents of Bert Williams, James Reese Europe, Fats Waller, and Bessie Smith. This was all happening in Harlem at the turn of the century and served as the underpinning of the Harlem Renaissance’s Jazz Age.

Given Harlem’s changing demographics, will its identity still be shaped, as in the past, by those who arrive as social outsiders?

I believe a real embrace and acknowledgment of Harlem’s changing demographics would offer the same creative possibilities that have derived from changes in the past. For that reason, I hate reading those often ballyhooed articles on Harlem’s “gentrification,” which are typically very coded and exclusionary. There’s never any mention of how Harlem embraced artists and musicians from New Orleans who made their homes here after fleeing Hurricane Katrina, or how a wave of West African immigrants was welcomed, who’ve infused the neighborhood’s fashion style, opened restaurants rich in African cuisine, and partnered to open pastry shops that rival the best in Paris.

When people write about gentrification in Harlem, they often have in mind Columbia University. How would you characterize the university’s relationship with Harlem?

I think Columbia University, in recognizing the African American identity of Harlem, spends an inordinate amount of time and effort trying to shake the connection rather than embrace it. Certainly, as an institution with substantial resources, there is lots that Columbia could bring to bear to benefit the community. Unlike New York’s Amazon headquarters fiasco, I think Columbia, with its long history in Harlem, was much more cognizant of neighborhood issues and more motivated to prod the City and advance a more broad-based community benefits plan. For example, adjacent to their expanded campus site is Harlem Piers, the result of a community-based effort to design a park along the Hudson River. Completed almost a decade ago, it is maintained through funds mandated in a community benefits agreement with Columbia University and was a harbinger of other collaborative projects. For example, Columbia also established a Community Scholars Program (I was one of the program’s first fellows), which offers residents of the adjacent Harlem neighborhood an opportunity to audit classes and access libraries and other resources, as well as to present their work to audiences on campus and in the community.

One way to manage change is through the stewardship of historic landscapes, which often includes landmarking and nominating sites to historic registers. But historical designations often depend on identifying architectural merit and integrity, while not everything worth saving is reflected in grand buildings—is that a problem that Harlem faces?

Indeed, one of the saddest aspects of landmarking in New York City is that common-place structures are not valued. Why save a tenement building if there are thousands of them? The same is often said for saving a movie theater, local restaurant, or bar-and-grill. But for African Americans, for whom such venues were often off limits or segregated, having access to equivalent places in their own communities was a significant achievement. For example, Harlem’s Theresa Hotel would rate in the Green Book as the equivalent of the Waldorf-Astoria. Many of Harlem’s synagogues and movie theater have survived today only because they became churches. Intimate venues, like Harlem’s Small’s Paradise or the Lenox Lounge, which offered a bar, dining, and music, once existed in abundance throughout the city. For Harlem’s literary giants like James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, and Maya Angelou, the vibe of the community could always be tapped at those spots. The Lenox Lounge, with its art modern edifice, illuminated nightly by distinctive neon signage, with a maroon and stainless-steel interior that could transport you back in time, to an imagined nod at Malcolm X or a drink at Billie Holiday’s table.

For many people, Harlem serves as a global sign-post, a signifier of the struggles, contributions, and successes the community has given to America. While recently rezoning 125th Street, Harlem’s main commercial corridor, a component of the rezoning exercise was to list potential landmark sites within the proposed zoning district. That list then goes to the Landmarks Commission, moving there at a snail’s pace, while the rezoning moves at a much faster clip. So, a property like the Lenox Lounge is now in an up-zoned area, making it an expedited target for demolition, especially if the owner wants to beat any landmark designation. For the City to make landmarking truly effective in areas targeted for rezoning, the review and approvals processes need to be on parallel timetables.

You sometimes speak of the “myths” of Harlem’s revitalization. What are a few of those myths?

In the truest sense, the really heavy lifting done to revitalize Harlem was largely community-based. Local faith-based and civic organizations established not-for-profit development arms and worked with all levels of government to develop, rehabilitate, and construct affordable housing and schools, and to foster commercial revitalization. Many people, like myself, were African Americans who came to Harlem with a love derived from family ties, the area’s cultural pull and mythic allure. We were fully engaged, laboring in earnest, and bringing to bare our professional skills to make Harlem, once again, a community equal to its revered place in our imaginations. Despite its tattered veneer, it offered us an affordable, welcoming, and nurturing place in the city to call home. Many of today’s leading New York developers cut their teeth partnering in these early efforts. But today these developers are circling like vultures, pressing not-for-profits for “fire-sale” deals on their undeveloped properties or sites, as the not-for-profits struggle to service their tenant base in what is currently an over-heated real estate market.

You’ve played a role in planning several public art projects in Harlem, including Frederick Douglass Circle and the Ralph Ellison Memorial. What are some tips you can share about achieving success on such projects?

A significant part of my career has involved organizing and advancing contemporary monuments and public-space enhancements in Harlem, to preserve African American history. The greatest asset in these projects is a clarity of vision, partnered with community engagement. The idea of collaboration as an exercise and education for all parties, inclusive of residents, designers, and city agencies, as well elected officials, need to be embraced. This way, we set priorities and learned to balance the trade-offs in a public way. For the Ralph Ellison Memorial, we collaborated with friends and neighbors of Mr. Ellison himself, our Councilman Stanley Michels (a Jazz-loving public official), and we established a partnership with the Riverside Park Fund, which served as our fiscal conduit.

For Frederick Douglass Circle, I benefitted from the earlier community outreach and planning by the Central Park Conservancy and the political muscle of then-Congressman Charles Rangel, who leveraged Federal Transportation Enhancement funds. The project’s design and implementation phases were supported by Cityscape Institute’s Betsy Barlow Rogers. Tagged the “Harlem Gateway Project,” our efforts brought significant enhancement not only to the Circle but also to the entire streetscape along Central Park’s northern edge and neighboring residences.