It Takes One: Margarita Blanco

Margarita Blanco earned a B. Arch. from Cornell University and practiced architecture for more than 25 years. She was a founding partner of the architectural firm Ricardo Bofill -Taller de Arquitectura de Las Americas, in Bogotá, Colombia. After earning her M.L.A. from Florida International University in 2005, she refocused her career on landscape architecture and helped establish ArquitectonicaGEO. She has served as co-founder and director at GEO for the past fifteen years, where she oversees most of the firm's projects. She enrolled in a Ph.D. program in landscape architecture at the University of Florida while continuing to manage the expanding firm and is now in the process of completing her first book, Designing Paradise: Diego Suarez, America's First Hispanic Landscape Architect. The book, which explores the relatively unknown professional career of Colombian architect and landscape designer Diego Suarez, is based on her doctoral dissertation.

How did Diego Suarez and his work at the Villa Vizcaya Museum and Gardens come to be the subject of your doctoral dissertation?

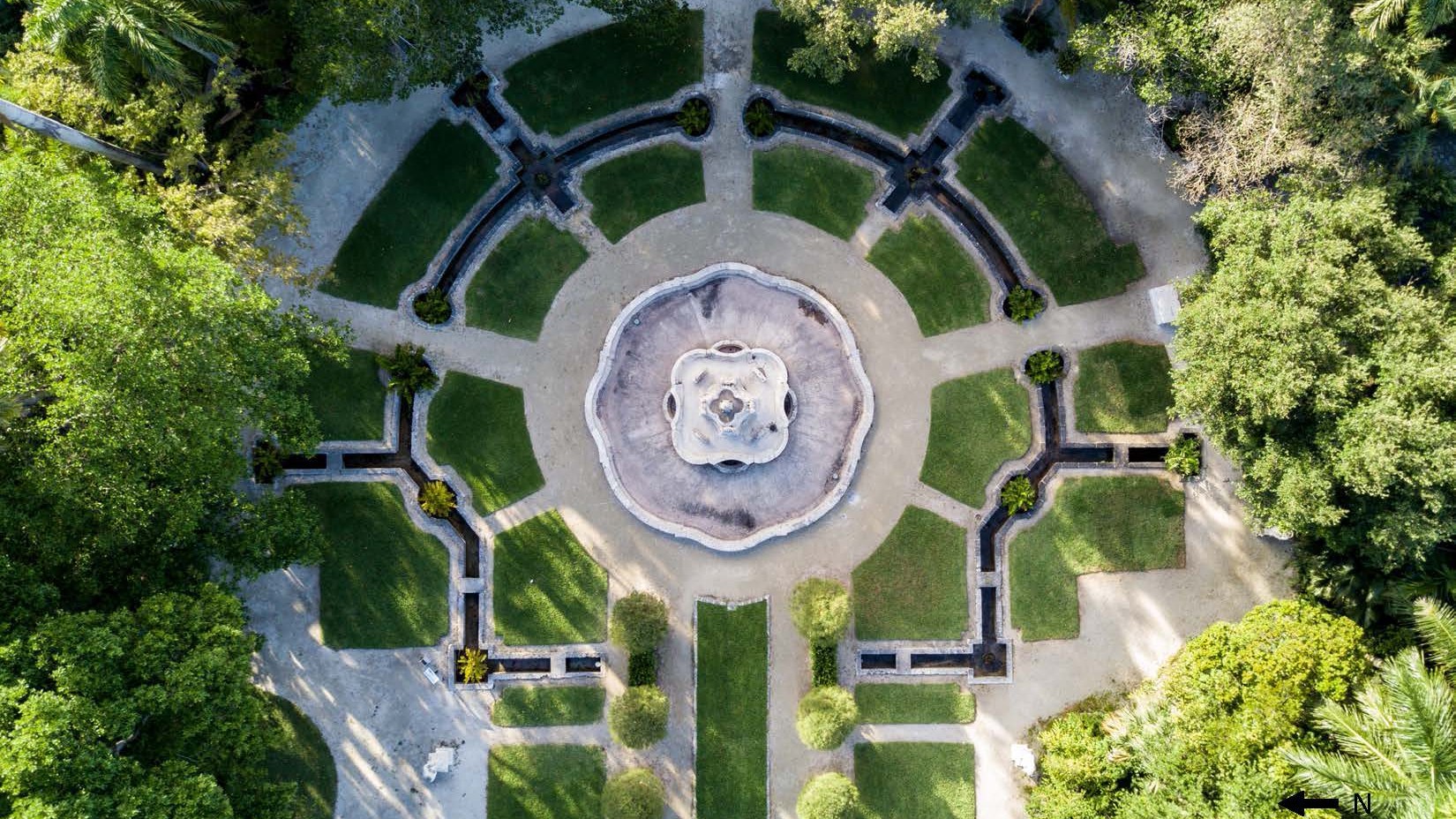

I have lived near Vizcaya for a decade and was inspired to do this research when I discovered that Diego Suarez was, like me, a Colombian by birth, a trained architect, and a landscape architect. I was intrigued to find out more about this mysterious man who had designed one of the great formal gardens of the early twentieth century and the only Italian garden in a sub-tropical location in the world. Yet, he was all but erased from the commonly told story of Vizcaya’s development.

Why did it take so many years for literature on Villa Vizcaya’s landscape to acknowledge Suarez’s contributions?

Several factors played a part in this. The biggest contributor was that Suarez lived in the shadow of Paul Chalfin, who served as Vizcaya’s project director until the site's completion in 1923. Another factor was that Suarez was a Latin American designer working in the United States at a time when the professions of architecture and landscape architecture were dominated by Caucasian men. Despite his upper-class upbringing in Colombia, he would have been considered an ethnic outcast in American high society. Finally, authors who have previously written on Vizcaya lacked the foreign connections and digital technology that allowed me to gather crucial pieces of information about Suarez’s work and reconstruct his life’s history.

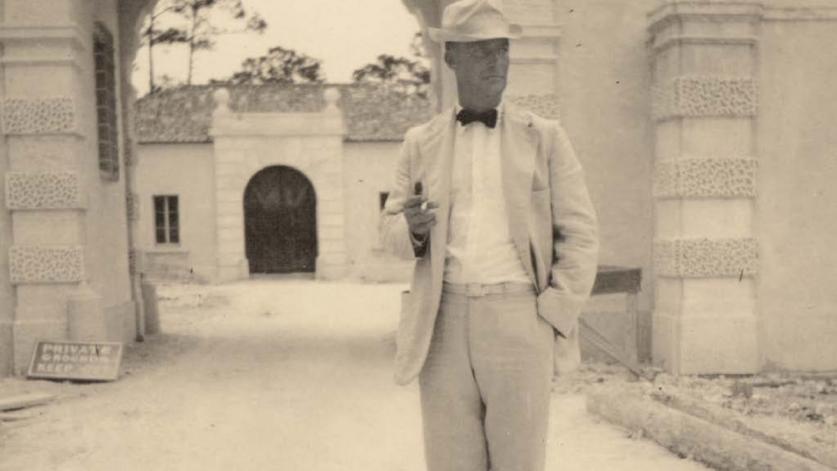

How did Suarez’s peripatetic background affect his approach to design?

At a young age, Suarez was exposed to transcontinental travel. His wealthy grandparents and parents, as with most of the Latin American elite of the time, looked towards Europe for the education of their children. Suarez's father had been a diplomat in Florence, where he met and married Suarez’s Venezuelan-Italian mother. He grew up among a group of people who were well-travelled and cultivated and therefore had exposure to the arts and to different languages. This rich heritage informed Suarez’s work and coalesced to inspire the many gardens and buildings he designed.

What was the American Renaissance Movement and what role did Italian garden design play in it?

The "American Renaissance" was a period between 1890 and 1915 when Americans held a great affinity for the Italian Renaissance. At a time when the rise of industry created unparalleled wealth and technological achievement, American artists and patrons alike sought a visual language for expressing the nation’s cultural ascendancy. Because many of the greatest artistic achievements of the Italian Renaissance were sponsored by merchant families, such as the Medici and Strozzi, leaders of America’s new industrial society – families like the Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, and Morgans – saw themselves as the appropriate heirs to the classically inspired tradition and appropriated many of the trappings and social customs of the Old World, which included palatial estates and formal gardens.

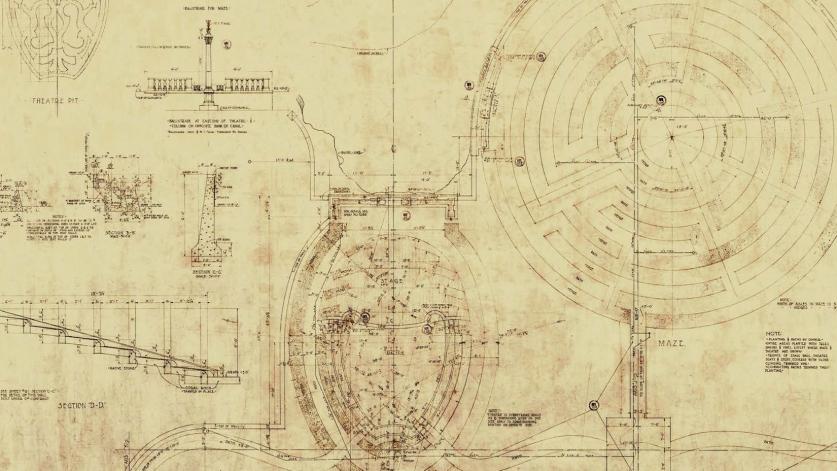

How was this movement reflected in Suarez’s design of the Vizcaya gardens?

The gardens are integral to the estate, and it can be argued that they are the premier creative element of the property. Their success is based not only on their extraordinary design, integrated with the best aspects of the local setting and environment, but also on an in-depth understanding of the formal Italian style by the architect and landscape architect who provided the foundation for the creative planning and design of Villa Vizcaya. Suarez’s most important contribution to the gardens was the Mound. The designer’s birth near the Andes Mountains, as well as his studies near the hills of Florence, greatly influenced his desire to create an elevated vista for Vizcaya by designing a large mound that was equal in size and stature to the main villa. As the first elevated landscape in Miami, the Mound emerges organically, becoming part of the landscape while symbolically linking the garden to the hills in Italy.

Following his design for Villa Vizcaya, Suarez refocused his career, becoming a prominent architect in New York. How did his experience in landscape design influence his architectural creations?

Despite having practiced as a landscape architect in only a limited way after leaving Vizcaya in 1917, Suarez's architectural projects included interior and exterior spaces in which landscape and garden elements comprised an important component. This is significant because it suggests that the landscape dimension of Suarez's work was forever present in his architectural projects.Traces of this can be seen in some of the projects he designed in New York City. Such is the case with the McLean Residence where, unlike other similar projects of the time, Suarez's treatment of the building clearly left room for a small, formal rear garden. This is also the case with the residential building planned for 76th street, where Suarez's treatment of the floor depicts what could have been a garden. The floor mimics a formal parterre, a sign that Suarez was thinking of landscape. Perhaps inspired by the vernacular houses of the Italian countryside with their exterior stairs, habitable roofs, and covered trellises, Suarez also proposed a green roof for each of these townhouses, a concept not yet developed for this residential building type in New York City.

What do you want readers to understand most about this landscape architect?

Because of his anonymity for almost half a century, scholars have failed to celebrate him as one of the major figures in American landscape history. Diego Suarez trained and practiced at a time when gardening in the Renaissance style was revived in both the New and Old Worlds. By tracing Suarez's history, this study sheds a new and interesting light on a talented but enigmatic practitioner whose life and works were previously undiscovered. From his gardens in Florence to his resting place in New York, he wove together the worlds of art, architecture, and landscape architecture to make a mark of his own, revealing how garden design, as with all forms of art, can illuminate the fundamental characteristics of its designers’ cultural background.