It Takes One: Matthew Coolidge

Matthew Coolidge is the director of the Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI) and serves as its chief curator and program manager. Before founding the CLUI in 1994, he studied environmental science and contemporary art at Boston University and worked for the global consulting company Fiasco. He has lectured at numerous colleges and universities and has been on the faculty of the California College of the Arts, teaching a graduate course on curatorial practice. Coolidge has written several books for the CLUI, including The Nevada Test Site: A Guide to America's Nuclear Proving Ground, and (with Sarah Simons) Overlook: Exploring the Internal Fringes of America with the Center for Land Use Interpretation. He spends most of his waking hours thinking about places. He also currently serves as the president of the Holt/Smithson Foundation, an organization dedicated to sustaining the creative legacies of artists Nancy Holt and Robert Smithson.

Can you briefly describe the Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI)?

The Center is an institution dedicated to improving the collective understanding about the built landscape of the USA. It produces exhibits, publications, online resources, and other publicly available material that explores, describes, and interprets the nation’s physical form.

It would seem that many of themes you explore overlap with traditional land-use planning, but that doesn’t really capture what the CLUI is or does. Does the difference come down to how these subjects are framed?

Context is at least as important as content, and the CLUI is composed of both. Our images, exhibitions, programs, and the institution itself, are frames within frames around views of places. We think as much about how these frames function—the context—as we do about what is placed within the frame—the content. The name of the organization says what we do: we look at the ways that land is used, and we interpret it. We also look at how others interpret it, as this is something everyone does, too, individually and in their own way. We simply established a “center” for doing so. We also understand that interpreting land use is a subjective process, and that’s one reason why we think about the frame—the point of view—so much.

What is the American Land Museum, and what are its objectives?

The American Land Museum is the ultimate curatorial structure we are working on, a kind of end-game. It contains artifacts of the American landscape, organized and presented to the public. Though composed of these physical objects, it may or may not end up having a physical form itself, but either way it will exist as a public venue that we hope will be open to everyone for free, forever, or as close to that as we can get.

The CLUI currently restricts its purview to the United States. Is there a particularly “American” stamp on the land?

I’m sure there is, but since we just look at the USA, it’s hard for us to make the comparison with other places. That said, the “American Stamp” is exactly what we are characterizing, and that stamp has global dimensions. We understand that, especially since World War II, much of humanity has been in an American age, but we limit our purview to the territorial boundaries of the USA for a number of reasons. One is because we have to draw the line somewhere, otherwise it’s just too much to do. Also, as Americans, we don’t want to be telling other nations what their places look like to us: they should do that themselves…hold up their own mirror. We are studying Homo Americanus by looking at its domestic habitat. We believe that the landscape of the nation itself is a cultural artifact composed of billions of other cultural artifacts, not all of them inherently interesting on their own, but all of them potentially interesting and capable of revealing things about who made them, depending on how they are interpreted. Artifacts are meaningless without interpretation. They are just shaped dirt, rock, plastic, metal, or whatever. With interpretation they become something.

In many of the CLUI’s articles, one senses the work and writing of earthwork artist Robert Smithson, who was influenced by New Jersey’s industrial landscapes. How have Smithson and other artists influenced the CLUI and its mission?

Some of the most interesting artists are interpreters working on the margins of culture, outside the boundaries of traditional disciplines and beyond economically and socially prescribed structures. They widen the spectrum of perspectival diversity. Smithson was one of these pioneers, venturing into the landscape like an applied-science fictionalist and a visionary theoretician. He seemed to understand that we now live in a built landscape, and he had a healthy sense of humanity in the context of larger, geologic time structures and its role as a geomorphological agent. He is one among many creative people who have expanded our awareness and bolstered a curiosity that is critical to a sustained and positive engagement with the world.

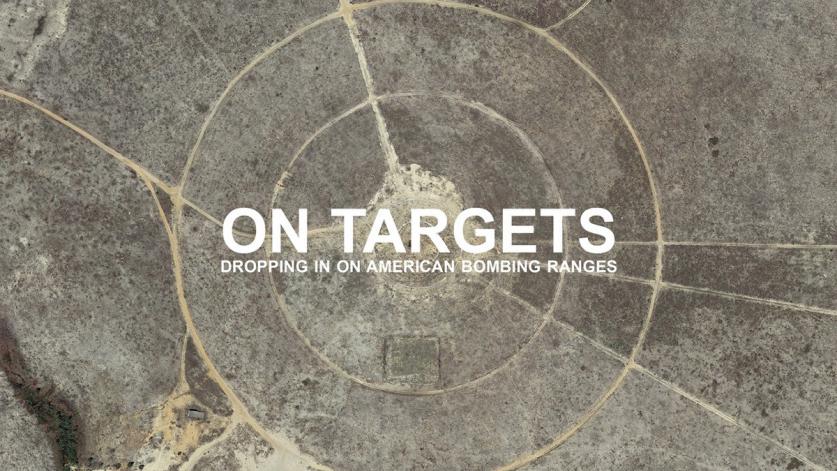

The landscapes you focus on are often byproducts of some other activity—a mine, a quarry, a bombing range. What place do these leftover landscapes occupy in the study of landscape history, and what new questions do (or should) they evoke?

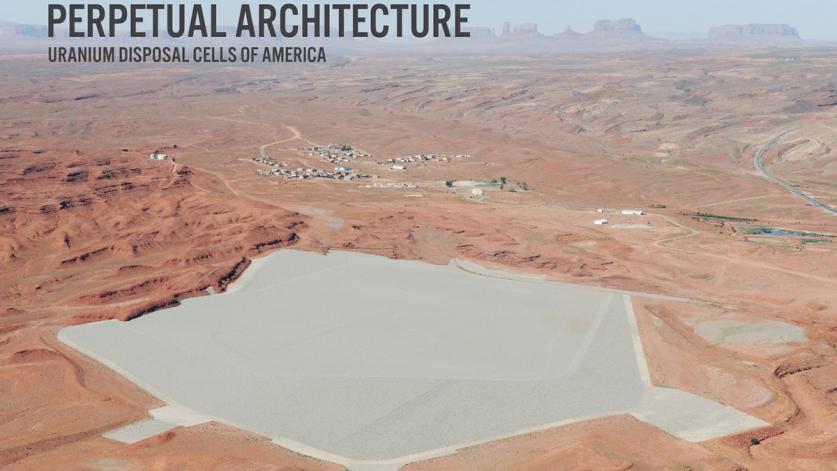

Products and byproducts are linked like yin and yang, pit and pile. The true meaning of ecology exists outside politics. It is simply the interconnectedness of all things within a large system, such as our planet. We value most of the stuff we intentionally make—buildings, iPhones, paper towels—but it all comes from somewhere, and goes somewhere when we are done with it. Material is shaped and reshaped, but doesn’t go away. To only value and consider things when they are in the form we intentionally make is, by definition, short-sighted and ignores the laws of thermodynamics. We have to learn to value and consider a wider range of objects, including, and especially, those that are normally cast aside by bias or created unintentionally.

The entire surface of the earth is now a product and byproduct of human activity, altered by anthropogenic chemistry, meteorology, and mechanics. All land is thus “used.” Nature, as it has been understood classically, as things outside of the artificial, human realm, no longer exists in physical form. All physical objects are now artifacts. But all this matter is still governed by the immaterial laws of nature. Though we use these laws to our advantage, we have not yet found a way to change them. Until we can do that, we ignore them at our peril.

The CLUI’s website features a land-use database. Have crowd-sourcing and Wikipedia changed the vision for how the database will develop and be used?

Yes, very much so, although probably in an inverse way. The database will likely always be made of content that we generate, including the text and ground-based photos from our own writers and photographers, not crowd-sourced or wiki-fied. Our Land Use Database was on the web when the web was in its infancy, and we were working with ESRI Arc-view GIS software to generate online maps that interfaced with our data. Now, even though our data is linked through Google Maps (because of their mastery of the use of scalable satellite imagery), it’s an anachronistic-looking thing, which we kind of like. A bit of a time warp, albeit one that works reasonably well with handheld devices. We are working on future versions that will take more things into account, but we also believe the rapid and perpetual changing of processes and technologies in the interest of progress has a downside, causing unnecessary, wasteful obsolescence, and a lack of historical and contextual awareness.

How do you choose the CLUI’s projects?

We start with the belief that probably every molecule on the surface of the Earth has been affected by human activity, either intentionally or otherwise, so everything on the surface of the planet can be considered “land use,” and as an artifact that harbors cultural meaning that can be extracted through interpretation. So, yes, we have a lot of ground to cover. It’s all about selection and its fancier cousin, curation. We developed a land-use classification system that divides all forms of land use into one of fourteen categories. This may seem absurd and arbitrary, but all institutions have to have some kind of order and a filing system. We draw from these categories selectively, so over time we do not focus too much on one subject over another, unless we do so intentionally. That is one factor in choosing projects: variety.

We have dozens of potential projects in various states of incompletion at any given time, and some end up on the front burner when they seem timely, or get energy, funding, or an externally imposed due-date. Ideally all these things line up together to bring a project to the public. We have committees and meetings where we discuss all of this, too, and that’s where these decisions are made.

How do you measure the impact of the CLUI?

I would say we don’t do that very effectively. We count heads that come in the door to see exhibits, we have totals for numbers of books sold, and we know how many hits we get on our website. But these things are no real measure of impact; they are just numbers. Ideas trickle and circulate in untraceable ways. We don’t do exit polling or post-mortems. Nor are we very good at promoting ourselves. We don’t do press releases, and we limit our media participation. This is partly because we found that media are voracious and could take all our time, reversing our priorities. Most media also tend to generalize too much, changing meaning. We want to be a raw artifact, as unmediated as possible, while not being completely invisible. We want to be part of the same landscape we find so interesting, full of surprises and possibilities. We want to be stumbled upon, rather than compete for mindshare. Let people come on their own terms, in their own way, and have a sense of discovery, just like in the act of exploration in the physical and virtual landscapes themselves. We put stuff out there, and if people are interested and engaged, they can usually find us, if they like. With the Internet, you can be found without shouting.