Judge Dismisses Suit Against Obama Center in Jackson Park

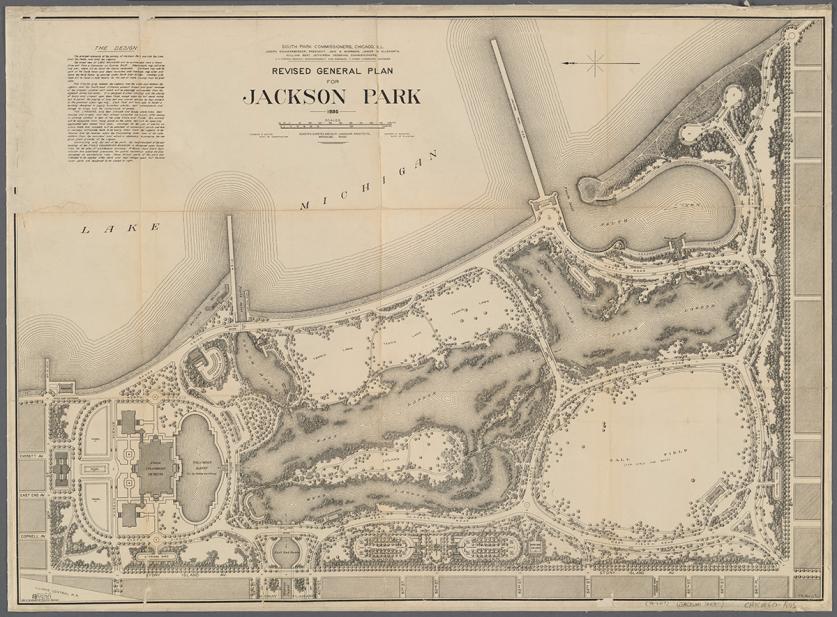

On Monday, June 11, 2019, U.S. District Judge John Robert Blakey dismissed the lawsuit seeking to block construction of the Obama Presidential Center (OPC) in Chicago’s Jackson Park. The lawsuit, filed against the City of Chicago and the Chicago Park District by the advocacy group Protect Our Parks and others, challenged the legality of building a privately run facility on historic, public parkland. Herb Caplan, of Protect Our Parks, told the Cook County Record immediately following the ruling that his group will appeal the decision “all the way to the Supreme Court if necessary.” Listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1972, Jackson Park was designed and redesigned by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., the ‘father of American landscape architecture,’ and was also the site of the famed World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893.

Going beyond the merits of the case, Judge Blakey, who was nominated to the federal bench by then-President Barack Obama in 2014, wrote in his ruling that “construction [of the OPC] should commence without delay.” The apparent zeal to see the project begin was not only inapposite; it was also premature because the OPC still faces several significant hurdles in the form of the ongoing federal-level reviews designed to protect the environment, as well as cultural and historical resources. Notably, those reviews have been dormant since March 2018. Contrary to Judge Blakey’s comments, reviews under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) must be completed “prior to the approval of the expenditure of any Federal funds on the undertaking or prior to the issuance of any license” [36 CFR 800.1(c)].

The recent remarks were not the first snub of the federal regulations to which the OPC is subject. In August 2018 TCLF alerted the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation that illicit work was underway to relocate a track-and-field facility in Jackson Park in preparation for the OPC, and it was only when the ACHP intervened that those premature activities were curtailed.

The next major step in the federal review process, expected any day now, will occur when the Federal Highway Administration presents to consulting parties (of which TCLF is one) the Assessment of Effects—the first formal iteration of the adverse impacts that the OPC would have on its surroundings—as mandated by Section 106 of the NHPA. Indeed, the purpose of the Section 106 review is to “seek ways to avoid, minimize or mitigate any adverse effects on historic properties” [36 CFR 800.1(a)].

An adverse effect is identified when “an undertaking may alter, directly or indirectly, any of the characteristics of a historic property that qualify the property for inclusion in the National Register in a manner that would diminish the integrity of the property's location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, or association” [36 CFR 800.5(a)(1)]. Some notable and immediately applicable examples of adverse effects are altering a property in a way that is “not consistent with the Secretary’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties,” or changing “the character of the property's use or physical features within the property's setting that contribute to its historic significance,” or introducing “visual, atmospheric or audible elements that diminish the integrity of the property's significant historic features.”

Moreover, the NHPA is not the only federal statute that must be satisfied before the OPC can be built. The project is being concurrently reviewed under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the Department of Transportation Act (DOTA), each of which, along with the NHPA, is governed by different regulatory requirements and standards, some of which explicitly refer to compliance with yet other federal laws and executive orders. Soon after the Assessment of Effects becomes public, for example, an Environmental Assessment (EA) should follow, as prescribed by the NEPA. Given what is already known about the proposed setting for the OPC, the EA should in turn recommend that an Environmental Impact Statement be completed.

For aside from the historicity of the park itself, which no one has questioned, reports and correspondences that have already been produced for federal agencies have documented the presence of abundant archaeological materials from 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (which have yet to be evaluated as both historical and cultural resources) and have identified several contributing features (code words for parts of the park with particularly high historical significance), such as roadways and landforms, that retain their historical integrity and yet would clearly be adversely affected—in some cases obliterated—by the OPC.

In short, what the OPC is facing, in addition to a protracted legal battle, is a federal regulatory matrix designed to safeguard the nation’s significant cultural and historical resources. What remains to be seen is whether the integrity of the federal review process can withstand the political pressures that have thus far steamrolled the local approvals process.