The Landscape Legacy of Raleigh-Durham

North Carolina Joins the Union

Founded in 1653 by Virginian colonists, in its early years North Carolina (a name the colony assumed by circa 1690) was primarily composed of forest and farmland. The topographically diverse landscape is defined by plains, plateaus, and several mountain ranges—the Great Smoky Mountains, the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Brushy Mountains, and the Uwharrie Mountains. Its temperate, humid climate accommodates land that is arable year-round, which encouraged colonists to establish expansive plantations, using slave labor for the cultivation of tobacco, cotton, rice, corn, and other fruit and vegetable crops, with North Carolina soon exporting these valuable resources to the other colonies. While the larger plantations with the greatest populations of enslaved people were sited along the coast, there were thousands enslaved in what would become the Raleigh-Durham region by the time America declared independence.

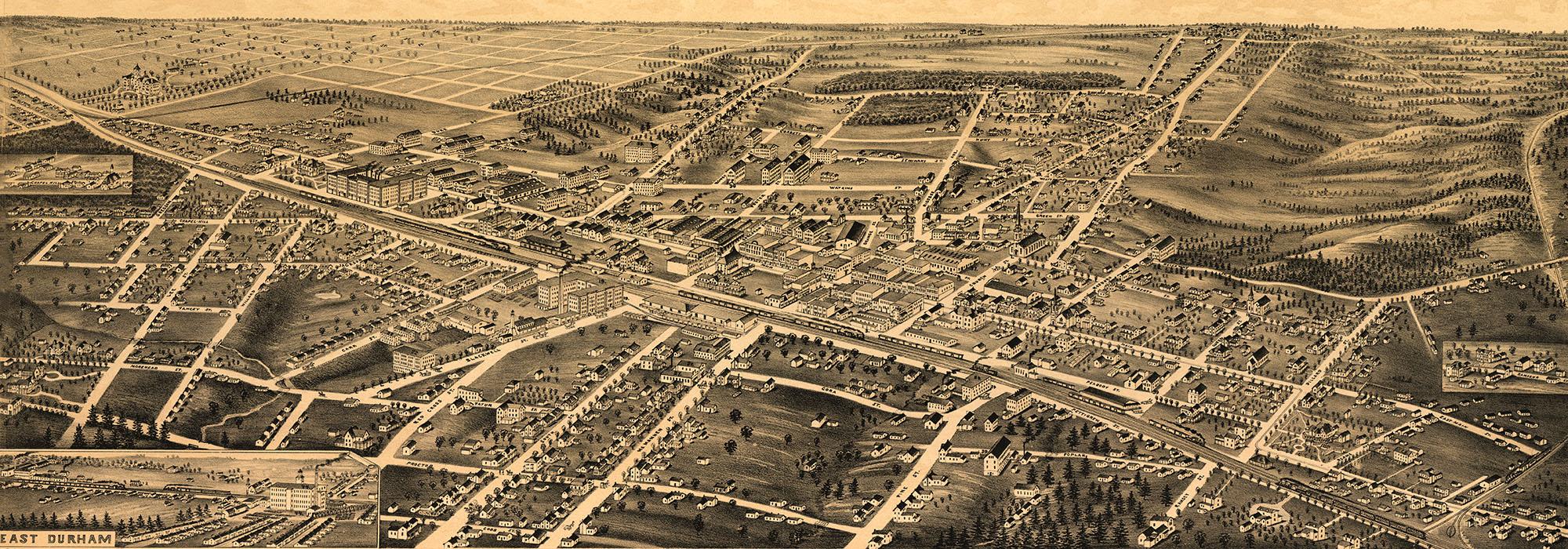

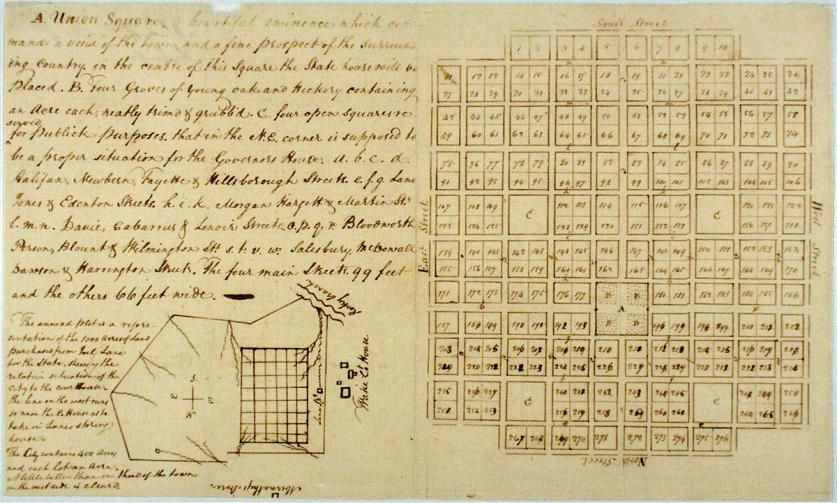

In 1789 North Carolina became the twelfth state to ratify the constitution. Having gathered informally and at impermanent locales since the end of the Revolutionary War, by 1792 the North Carolina General Assembly vied for a capital city to be located at the geographic center of the state. A 1,000-acre plot of thickly forested farmland was purchased from local landowner Joel Lane, and surveyor and former North Carolina state senator William Christmas was hired to develop the plan for the city. Christmas modeled his design after William Penn’s Philadelphia Plan, creating a one-square-mile grid of perpendicular streets with integrated green space, centered on Union Square (now Capitol Square), which was designated as the site of the State Capitol building. Four 99-foot-wide thoroughfares acted as the main arteries: Fayetteville, Halifax, Hillsborough, and New Bern Streets. Each of the city’s quadrants contained a four-acre square with public green space. When the construction of the plan was completed in 1794, Raleigh was dubbed a “city of streets without houses.”

The early 1800s saw incremental growth in the city, with a population hovering around 700. An 1831 fire devastated many buildings, including the original brick capitol, and in 1833 a grand Greek Revival structure designed by architects Ithiel Town and Alexander Jackson Davis was constructed in its stead, surrounded by informal open lawn.

In 1856 two major rail lines were completed, connecting Raleigh to other fast-growing cities across the state, including Goldsboro, Greensboro, Salisbury, and Charlotte. Just 25 miles northwest of Raleigh, a new city was emerging. Durham, which had primarily been composed of plantations, was born of necessity—a depot for the steam trains to refuel along the major route between Hillsborough and Raleigh. In 1861 the outbreak of the Civil War abruptly stalled both Raleigh and Durham’s development.

Civil War and Reconstruction

The Civil War greatly impacted the region. Raleigh had many open spaces that were used for military purposes, such as the Confederate Camp Mangum west of the city that would later become the North Carolina Museum of Art, and Dix Hill, overlooking the city from the south, the site of Dorothea Dix Hospital (designed by Alexander Jackson Davis in 1850) and eventually Dorothea Dix Park. As the state capital, Raleigh was not only host to significant political gatherings leading up to and during the war, such as the 1861 Secession Convention at the Capitol, but its streets and public spaces became prominent gathering points for confederates and unionists alike. Fayetteville Street, extending south from the Capitol, for example, was the site of the march of Union troops toward the State Capitol in 1865. Following the Civil War, the street began to emerge as Raleigh’s commercial spine, while other areas became increasingly residential.

Several new residential neighborhoods also developed at the fringes of the expanding city. In 1867 a densely wooded area to the northeast of the original mile square was established as a Confederate cemetery. Two years later, the rolling landscape directly west of the rural cemetery was developed as Oakwood, Raleigh’s first suburb, which appealed to the city’s white middle class. Concurrently, Raleigh’s significant African American population began creating its own neighborhoods (with their own schools, cemeteries, and other facilities), including Method and Oberlin, founded as freedmen’s villages in the late 1860s. Rapid suburbanization continued into the twentieth century, accelerated by the advent of the street car, which arrived in Raleigh in 1891.

By this time, two of the squares designated as public space in the Christmas Plan had been relegated for development. On Caswell Square, to the northwest, a school for the blind was constructed in the 1840s, while Burke Square, to the northeast, became the site of the Governor’s Mansion in the 1880s. Beyond the three remaining downtown squares, public space was limited. To remedy this, in 1887 Richard Pullen, the developer who had previously founded Oakwood, donated 66 acres of farmland to the City of Raleigh for the establishment of a public park. Jim Crow laws prohibited African Americans from using many of the park facilities, and in 1937 John Chavis Memorial Park was established approximately two miles away to serve as Pullen Park’s “separate but equal” counterpart.

From 1900 to 1920 Raleigh’s population nearly doubled (from approximately 13,600 to 24,400), and in 1913 the Woman’s Club of Raleigh commissioned urban planner Charles Mulford Robinson to produce “A City Plan for Raleigh,” which identified potential improvements to the city in three arenas: the business district, residential streets, and open spaces. While some of his recommendations were cosmetic, such as updates to street lights and signage, Robinson also touched on greater themes, including the need to reinvigorate Capitol, Nash, and Moore Squares, which had been neglected as a result of the war.

In 1928 Olmsted Brothers created a master plan for Capitol Square, transforming the state building’s surroundings from piecemeal development into formalized, publicly accessible green space. The firm designed a park-like setting with curvilinear pebbled paths leading through geometric lawns, realigned several statues to create a more orderly layout, and introduced landscape features including a stepped plaza with two small fountains at the capitol’s east entrance.

Spurred by educational and commercial opportunities in predominantly African American neighborhoods, a new black middle class was also emerging at this time. The 1914 opening of City Market opposite Moore Square’s southern edge, and the 1920s development of Hargett Street as “Black Main Street” on its northern edge, established Moore Square, one of the few integrated spaces during segregation, as the central core of African American culture in Raleigh for the next several decades. Nash Square remained relatively unchanged until the 1940s when the Works Progress Administration provided funds for its redesign.

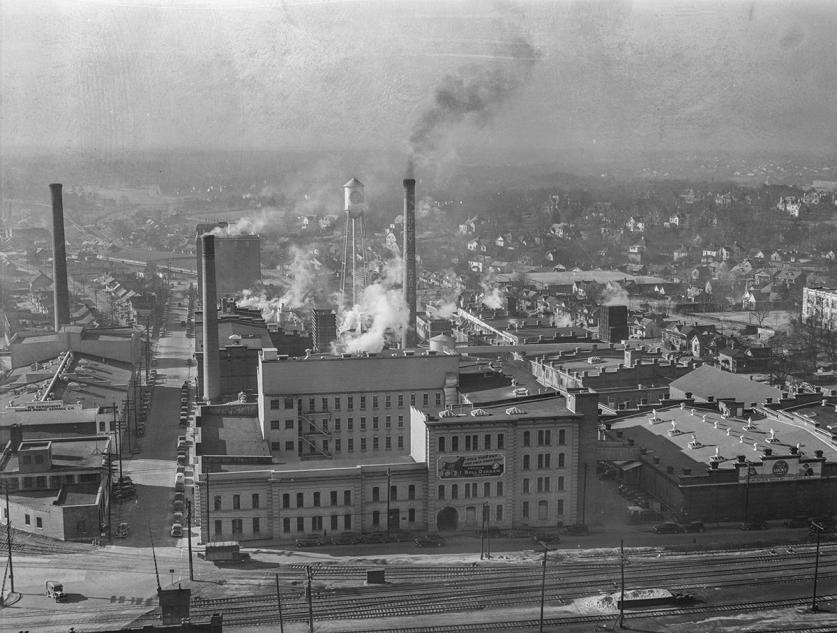

From the latter half of the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century, the nearby city of Durham emerged as a center of commerce—primarily in tobacco. Following the Civil War, Washington Duke returned to his hometown of Durham to make his fortune in the tobacco industry. In 1890 his family business, Duke & Sons, merged with its four major competitors to become The American Tobacco Company, relocating to the Italianate W. T. Blackwell & Company Factory at what is now the northern end of the American Tobacco Campus.

Like Hargett Street in Raleigh, Durham’s Parrish Street became a nucleus of African American-owned businesses within a predominantly white neighborhood at the turn of the century. The district was praised early on as a model of economic empowerment for African Americans in the segregated South. The moniker “Black Wall Street” gained traction in the 1950s, recognizing the many financial enterprises that thrived there, such as the Mechanics and Farmers Bank, the headquarters of which was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1975.

Becoming the Research Triangle

Several significant educational institutions were founded or expanded upon following the Civil War. While the term “Research Triangle” did not enter the nomenclature until the 1950s with the establishment of Research Triangle Park, the area had long been a hub for higher education. Founded in 1789, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was the first public university in the nation. Initially conceived as a village on 1,300 undulating acres of forested land, in 1818 the forest campus was transformed into formalized grounds when professor Elisha Mitchell introduced diverse trees planted in rows. In 1851 a Picturesque plan by Alexander Jackson Davis was implemented. Campus development shifted southward in a haphazard fashion after the Civil War, until the 1920s, when McKim, Mead and White developed a Beaux-Arts plan.

Ten miles northeast of UNC Chapel Hill, in 1892 a small school called Trinity College moved to a new campus. In 1924 a major endowment by James Duke elevated the school to the status of a full university, and the Duke University grounds were expanded south and west, eventually comprising nearly 9,000 acres across three contiguous campuses. In the 1930s Olmsted Brothers, led by Percival Gallagher, designed the campus grounds, which became one of only two major projects completed by the Olmsted Brothers firm in the region (the second being Capitol Square in Raleigh).

Meanwhile, approximately 25 miles to the east, a new public university was conceived in Raleigh. North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (now North Carolina State University) was founded in 1887 pursuant to the Morrill Act of 1862, which made federal land available for the purposes of establishing higher education facilities for the teaching of agriculture, mechanical arts, and military science. Similar to the other campuses in the region, it was developed as a series of Beaux-Arts quadrangles, though the campus would later expand dramatically and shift its landscape design according to Modernist principles. The University’s School of Design, established in 1948 with Henry Kamphoefner as its first dean, drew renowned Modernists to the region, including architects, landscape architects, and designers.

Other significant schools in the region include Meredith College (established in 1899), St. Augustine's University (founded in 1867 by Episcopal clergy for the education of freed slaves), and Shaw University (founded as the Raleigh Institute in 1865), the oldest historically black university (HBCU) in the Southern United States.

Modernism, Urban Renewal, and the Future of the Region

Modernism became hugely popular in the region, and its influence is particularly evident on the campuses of North Carolina State University and Meredith College, where landscape architect Richard Bell designed the University Plaza (also known as the “Brickyard”) and amphitheater, respectively.

Bell and his contemporaries also greatly influenced Raleigh’s downtown area. In 1965 Bell and Associates designed two narrow plazas replacing parallel side streets in downtown Raleigh, running across the city block bounded by Fayetteville, Hargett, Wilmington, and Martin Streets. The closure of the two streets to traffic was the precursor to the redevelopment of Fayetteville Street as a pedestrian mall in 1977, with a master plan by landscape architect Lewis Clarke.

In 1976 Halifax Street, north of Capitol Square, was closed to traffic, and Bell developed it as a plaza for a newly expanded government complex. The openness of the pedestrian mall increased freedom of movement while strengthening a stronger visual and physical connection between the Capitol and the new Legislative Building, also designed by Bell in collaboration with Edward Durell Stone.

These and other urban-renewal projects led Raleigh’s citizens to establish a system that would ensure their continued access to green space. In the early 1970s William Flournoy, then a graduate student at North Carolina State University, submitted a Capital City Greenway master plan to the city council, and by 1975 several individual trails had been constructed. Over the next 30 years, more than 100 miles of greenway were developed based on his recommendations.

Raleigh has entered a renaissance in the 21st century. National dialogue about Confederate monuments and the role of heritage in planning in the New South are shaping conversations about the city’s future, while the reopening of Fayetteville Street to traffic in 2006 and the ongoing redesign of Moore Square are just two examples of the transformation taking place downtown. On 308 acres overlooking downtown Raleigh, Dorothea Dix Park, which opened in 2015 on the site of the former plantation and then psychiatric hospital, is poised to further this transformation. Rich in natural and cultural resources that trace the history of the region since its early settlement, the park addresses a centuries-old need, identified by Robinson in his 1914 City Plan: “…the need—which we must hope a higher public spirit and keener social conscience will satisfy—of additional open space.”