Olmsted Brothers' Only Work in Venezuela at Risk

Editor's Note: This entry is excerpted from a more extensive article in The Urban Times.

The Caracas Country Club, a 1928 residential community and golf course located in the middle of the Caracas valley, is the only Venezuelan project by Olmsted Brothers. This pioneering landmark of urban and landscape design embraces the natural scenery and resources of the valley and has helped protect it from the dense, surrounding urban development. Listed in 2005 as a National Landmark, the green, urban oasis and original features of the "Caraquenian Central Park" are increasingly being encroached upon by public and private interests aiming to capitalize on the property’s central location.

(upper) Caracas Country Club´s landscaping and golf courses,

1958; (lower) Caracas Country Club Golf House, 1930, architect

Clifford Charles Wendehack, images from the Archives of

Fundación de la Memoria Urbana, CaracasHistory

The original Caracas Country Club was established in 1922 around a small golf course located in the La Quebradita part of the city. During the late 1920s, the Syndicate Blandin was founded to spearhead expansion of the golf course and clubhouse. The association included many club members and was named after the Hacienda Blandin, a plantation nestled on the eastern side of the Caracas valley, where the residential development would be built. The Blandin plantation was famous for introducing coffee cultivation to the Caracas valley in 1786 and also for its magnificent specimen trees and mature native landscape, sweeping vistas, and stunning hacienda located on the banks of a creek.

The Syndicate Blandin decided to develop a new and integrated urban experience, the first of its kind in the country, on the hacienda's lands and hired Olmsted Brothers to do the layout and landscape design between 1928 and 1934 (more than 80 drawings and plans were completed by the firm for the project). American golf course specialist Charles Banks was brought on to design the courses in collaboration with James Frederick Dawson and Leon Henry Zach of the Olmsted Brothers firm, and California architect Clifford Charles Wendehack assisted Venezuelan architect Carlos Guinand Sandoz in designing the structures. In engaging the Olmsted Brothers firm, the commission sought to create a sensitive urban design and landscape that conserved the beauty of the local landscape. A 1916 statement by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., reflects his understanding of this concept and indicates a philosophy the firm would later apply in the design of the Caracas Country Club, noting that it is important, “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

For the Caracas Country Club design, Olmsted employed one of the firm’s overarching design principles: preservation of "the irreplaceable and unvalued domains of the past.” He incorporated and protected a great deal of the existing conditions around the hacienda and maintained the natural topography of El Avila Mountain foothills, laying the greens out north to south within the valley in order to afford wide views to the mountain and to the southern hills. The site’s irregular shape and corresponding curvilinear street pattern allowed the conservation of large masses of specimen trees and palms that once grew prolifically in the area. The firm also respected the configuration of the hacienda’s main road, the Avenida Principal de Blandín, once lined with Chaguaramo palms and now lined with Washington filfifera palms. The bridge over the Chacaíto Creek and the site of the Hacienda Blandín, both cultural elements dating to the 18th century, were also reaffirmed in their traditional settings and incorporated into the Olmsted design. Today, the Caracas Country Club serves not only an ecological and environmental sanctuary, but also as a rare record of the cultural landscape's palimpsest.

Threat

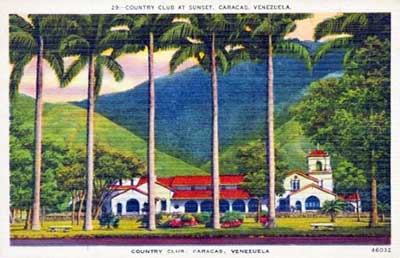

Postcard of the Caracas Country Club, 1925Despite its significance and its value for the quality of life it provides, preservation of this first large-scale residential landscape architecture project in Venezuela is an ongoing issue that continues generating controversy. Since 2000, sustained real estate development pressure has endangered the entire neighborhood. And, following its 2005 landmark designation, the golf courses were nearly expropriated by the government in 2007 in order to build socialized housing. Significantly, the houses and gardens were not included in the 2005 designation, and political and economic pressure to alter zoning regulations possibly to allow redevelopment into rentable apartment towers. There is also talk of converting the Caracas Country Club into a public park, and transportation issues are now being leveraged as an excuse to force rezoning.

Get Involved

The Venezuelan Chapter of Docomomo has taken on the responsibility of garnering international attention for the conservation and preservation of this unique historic designed landscape. In Venezuela’s difficult political climate, with the fragmented condition of the Caracas municipal government, it is almost impossible to convene a balanced public discussion about the site's alternatives that takes into account its significant history. Docomomo Venezuela is seeking help to organize a full historical dossier of the site and generate an international discourse on its urban, ecological, and preservation values and merits. It also maintains an ongoing conversation with the Caracas Country Club Board and other interested parties, including the Alcaldia Metropolitana de Caracas, about the importance of preservation issues. Send a letter or email supporting the preservation of the Caracas Country Club to: Docomomo Venezuela, Avenida Orinoco, Cabrini 1, Las Mercedes, Caracas 1060, Venezuela or docomomo.ve@gmail.com

For more information about how to help, please contact

Docomomo Venezuela:

www.docomomovenezuela.blogspot.com/

docomomo.ve@gmail.com

References

Gómez, Hannia, "Olmsted in Blandín, Preserving the Modern Heritage", Landscape Architecture, The Urban Times, May 23 (2011).

Seventy-nine plans and drawings completed by the firm for the project, plus an album with 112 historic photos exist in the Olmsted Archives of the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site, Brookline, Massachusetts. Three folders of client-architect correspondence (Job No. 7947) are in the collection of the Olmsted Papers, Olmsted Associates Records, Series B, from the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.