Lessons from the Landscape - Reflection by 2024 Cultural Landscape Fellow

As The Cultural Landscape Foundation’s (TCLF) 2024 Danette Gentile Kauffman Cultural Landscape Fellow, I spent eight weeks crisscrossing Seattle researching, photographing, and writing about a diverse set of landscapes. Each site held visual cues as well as unseen layers of social, ecological, political, and economic connections. As I reflected on and considered these sites in a wider context, patterns and values emerged, revealing the “Emerald City’s” unique character.

As the weeks passed, it became clear that Seattle is a city of innovation. Bold moves made by key visionaries laid the groundwork for a strong culture of ecological sustainability. This culture resonated with me because it is urgently needed in my hometown, Salt Lake City. Its namesake, the Great Salt Lake, is shrinking and experts warn it could disappear in a matter of years, creating an ecological disaster. A megadrought and warming temperatures have impacted lake levels, but the primary cause for alarm is decades of unsustainable water diversion for commercial, industrial and residential use.

As the fellowship drew to a close, I found myself wondering how two western cities, founded just four years apart in the mid-nineteenth century, diverged so significantly in their attitude toward the natural world. While this question could be examined from many different angles, using a variety of sources, I looked to the landscape for answers.

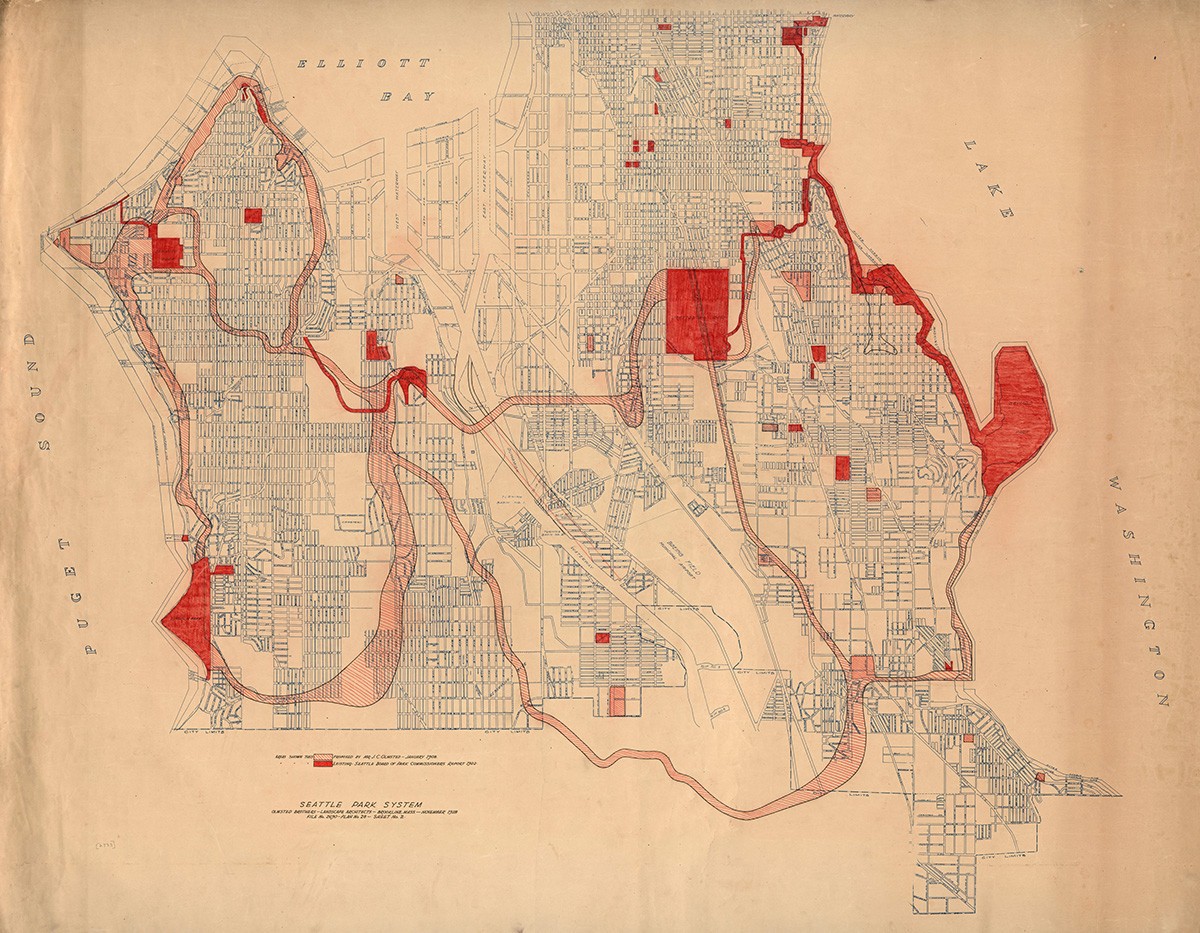

The first clue is found in Seattle’s network of parks and boulevards, consistently ranked among the best in the country. The initial idea for the city’s integrated park and boulevard system was conceived by park superintendent and landscape architect Edward O. Schwagerl (1842-1910) in 1892. His plan called for wide boulevards connecting four large parks in each quadrant of the city. The Panic of 1893 delayed action, but by the turn of the century Seattle had rebounded economically, successfully marketing itself as the gateway to the Klondike Gold Rush. In 1902 a full-page article in the Seattle-Post Intelligencer, endorsed by leading citizens, called for the city to acquire land for an extensive park system. Not long after, the landscape architecture firm Olmsted Brothers was hired to create a comprehensive parks and boulevard plan. Engaging the Olmsted firm to plan for the future so early in Seattle’s history, proved to be a bold and visionary decision. The Olmsted plan preserved many of the best views and waterfront access points for public enjoyment, creating large naturalistic parks where individuals could connect with nature in an urban setting. Seattle’s early investment in public green space undoubtedly influenced future public attitudes toward the environment.

Researching Seattle’s Denny Park revealed another visionary: city engineer Reginald H. Thompson (1856-1949). Early on Thompson planned for tremendous growth – believing strongly in Seattle’s potential to become a great city – when many others lacked such foresight. He arrived when the population was some 3,500 and spent his career altering the topography of the heavily logged city and designing the infrastructure to support what would become a city of over 450,000 by the time of his death. One of Thompson’s most influential moves was to secure water rights to the Cedar River watershed nearly 30 miles outside Seattle to provide clean water and power to the city’s growing population. A more controversial, but nevertheless bold move, was his decision to regrade entire neighborhoods to make the city’s typography more conducive to commerce. During the final regrade in 1930 Denny Park was lowered approximately 60 feet.

This forward-thinking spirit likely influenced the Washington State Legislature’s bold move to create the nation’s first Department of Ecology in 1970, predating the federal Environmental Protection Agency, and serving as a model for states around the country. In 2023 Seattle was recognized by the United Nations Environment Program as a Role Model City.

In many ways, Salt Lake City was founded by bold visionaries focused on establishing a community for religious worship. The tight-knit and highly organized group sought solace from religious persecution, selecting a dry valley to build their new Zion. Upon the Mormon’s arrival in July 1847, they immediately dammed City Creek, fed by snowmelt in the Wasatch Range to the east, to soften the soil and plant crops needed to survive the coming winter. This enterprising group soon established an agricultural economy dependent on irrigation and made the desert “blossom like a rose.” By 1865 gravity fed irrigation canals supported more than 150,000 acres and 65,000 people.

Today Utah still allocates water based on the original agrarian economy system, despite that agriculture represents just 0.5 percent of the state’s gross domestic product. While water rights law is much too complicated for this reflection, part of the current dilemma is grounded in the long-held cultural identity of this region as an agricultural land. This perception persists although farms now primarily produce crops for feeding livestock.

The state experienced the highest population growth in America from 2010-2020 and the best agricultural lands, situated in fertile valleys or foothills along the Wasatch Front, are being converted at a rapid pace for housing. In Utah an imbalance has emerged between water use and public good. The health and welfare of more than 1.6 million people living and working along the Wasatch Front is in danger from dust pollution caused by a shrinking Great Salt Lake while agriculture uses approximately 63 percent of the region’s water. Owens Lake in California stands as a vivid precedent of the environmental dangers a shrinking terminal lake can cause. Before costly mitigation efforts, the dust from the dried lake accounted for the nation’s highest source of PM10 (airborne particulate matter with a diameter of ten microns or less), which when inhaled, can lead to adverse health effects. The Great Salt Lake is twelve times larger than Owens Lake.

Utah needs bold visionaries like Edward O. Schwagerl and Olmsted Brothers who valued nature and planned strategically many years into the future. We need people like Reginald H. Thompson with bold ideas. The residents of Utah need a wide-spread cultural shift in their attitude toward water. While founders diverted water for physical survival, reducing diversion is now key to Utah's economic survival. Solutions are being explored by non-profits, local and state government agencies, educational institutions, and concerned individuals. Hopefully some solutions will prove bold enough to move the state to a brighter future. Borrowing from Native wisdom shared by Darren Parry of the Northwest Shoshone band whose lands once included areas around the Great Salt Lake, let us call on leaders to think seven generations in the future when making decisions regarding the land.