A Lester Collins Landscape Hiding in Plain Sight

Modernist landscapes are often layered spaces—palimpsests of choices and design histories that can only be completely understood through research, analysis, and first-hand accounts. That is the case with the Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden, prominently located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Home to more than 60 works of exemplary sculpture, the garden is a contributing feature to the National Mall Historic District and is now slated to be redesigned by Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto. Before that can happen, however, the project is being reviewed under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act.

Although the Federal review is still in its initial stages, it has thus far failed to recognize as part of the garden's Period of Significance the Modernist design of esteemed landscape architect Lester Collins, which is essential for correctly assessing the potential adverse effects of any new plans. What follows is a fuller account, based on archival research, than has been given so far of Collins’ involvement with the Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden in the late 1970s. As records from the period make clear, his extensive but sensitive work was an adept response to several complex and multifaceted challenges.

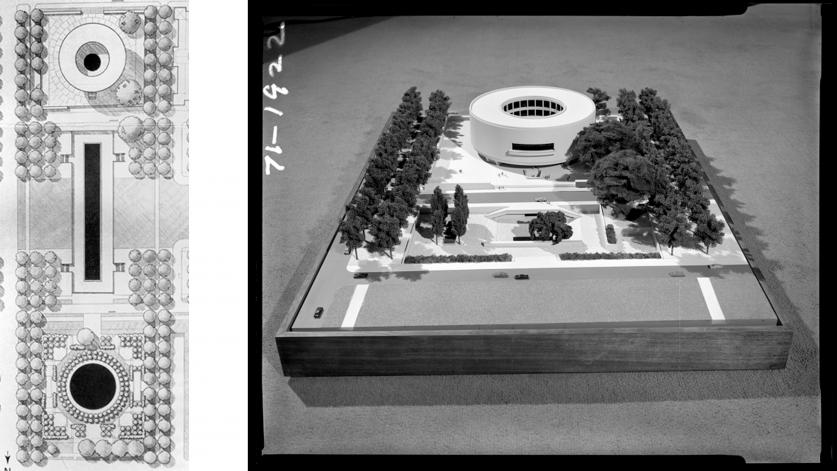

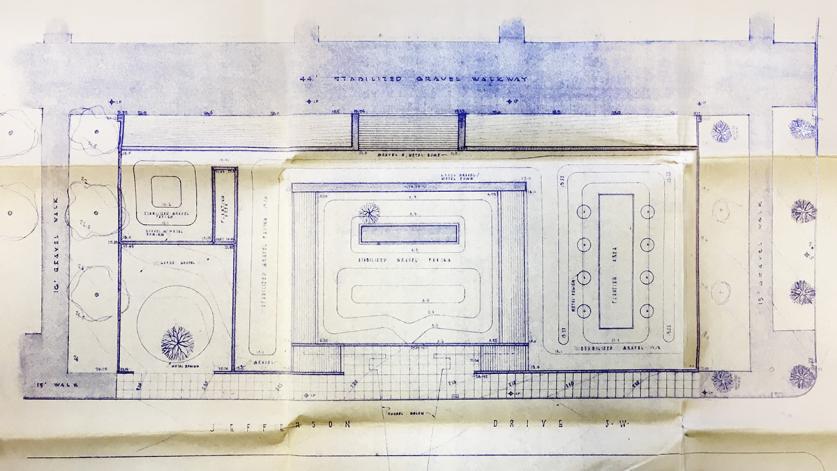

In November 1966 the U.S. Congress authorized construction of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, to be located on the southern side of the National Mall, midway between the Washington Monument and the U.S. Capitol. In early 1967 Gordon Bunshaft, of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, was commissioned as the architect for the project. Bunshaft created a plan for a drum-like museum and an outdoor sculpture garden that together were to occupy some 4.5 acres. The sculpture garden was first conceived as a sunken, rectangular space that stretched across the full width of the Mall, covering approximately two acres. More than one-third of that acreage was to be occupied by a long, rectangular pool surrounded by a pebble-covered apron serving as the setting for sculpture.

Although it was not without controversy, reviewing authorities approved Bunshaft’s plan in July 1967, and the ground was broken in January 1969. But critics and the public soon registered their opprobrium for such a bold interruption of the longitudinal vista of the Mall—particularly by a stark, Modernist intervention. In January of the following year, Congress weighed in, eventually stopping construction. Heeding advice from critics, Bunshaft turned the axis of the garden 90 degrees, creating a terraced landscape on 1.5 acres just north of the museum’s plaza and separated from it by Jefferson Drive.

Almost entirely devoid of planting materials (in particular, much needed canopy trees for shade) and bounded by concrete-aggregate walls, the garden would retain the pebbled surface around a much smaller sunken pool (now fourteen feet below the Mall) reached via various flights of stairs that connected several terraces. The space opened to the public on October 4, 1974. Prominent critics immediately had their say:

The sculpture garden or court that is one of the museum's principal features fights the large-scale sculpture to a draw; the pieces seem to do battle with the hard, bleak geometry of their setting, losing scale and power. This garden is so lacking in grace that it will not close the controversy over whether it should have been permitted to extend into the open green of the Mall… [] … Why have the subtle, sensuous lessons of paving and planting and procession of spaces of the Museum of Modern Art sculpture garden never been learned

—Ada Louise Huxtable, New York Times, October 6, 1974

It also soon became clear that the austere landscape, lacking in shade and vegetation, was not a welcoming place during the Washington summers. Moreover, the many stairways and pebbled surface were difficult to negotiate for those with physical challenges or for baby strollers. By the summer of 1976, S. Dillon Ripley, the Secretary of the Smithsonian, was already actively engaged in developing a new plan for the garden. In a July 1 memorandum to Abram “Al” Lerner, the museum’s first director, and James Buckler, the director of the Smithsonian’s Office of Horticulture, Ripley indicated that he did not favor hiring “the firm of Zion in New York” (i.e., Zion & Breen Associates) but rather felt that the Smithsonian’s in-house team was capable of solving the garden’s problems, including “the gravel situation.” Notably, in this early correspondence, Ripley mentions that Buckler had formed a “landscaping and horticultural subcommittee” to which Lester Collins was a “splendid advisor.”

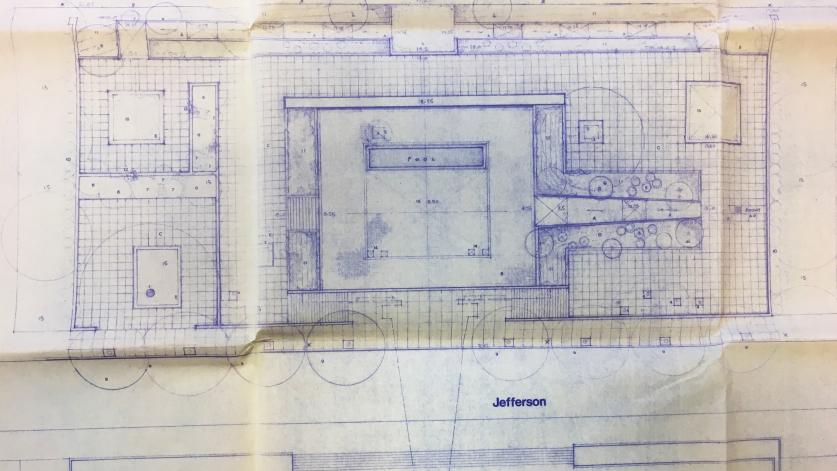

In an August 18 memo, Lerner enumerated his “long-term objectives” for the sculpture garden, saying that any comprehensive plan must consider four key elements: (1) “Access by the handicapped,” with mention of a ramp, but acknowledging that “access to the lower level…presents a more difficult problem,” and that “wheelchairs cannot negotiate the existing pebbled surface”; (2) “Landscaping,” to improve “the appearance and comfort of the garden,” which becomes an “almost desert-like expanse” during the summer; (3) “Lighting,” noting that a plan from Jules Fisher & Paul Marantz, Inc., was already in hand, but must be reviewed with “any changes that are planned”; and (4) “Safety,” recalling that accidents had resulted from loose pebbles on the stairs. Under the second provision, for landscaping, Lerner also noted a desire to “create more secluded areas for individual works of art,” adding, “the guidance of a professional landscape architect is badly needed,” especially in determining “how paths might best be laid between the grassy areas” and “what plant material is most suited, both in terms of appearance and maintenance, to carry out these plans.”

Other memos from this period show that Collins was providing advice about plantings for the Hirshhorn, but his official commission to redesign the sculpture garden ultimately came in April 1977, when he agreed to “work on a plan for the Hirshhorn Museum’s Sculpture Garden.” He indicated his willingness to reduce his normal hourly rate from $40 to $25 dollars per hour, and to cap his total fee at $4,000 because “a most fascinating and challenging job is involved.” Collins then set about producing a new plan for the garden that would meet the requirements set forth, without exception.

On September 12, 1977, Secretary Ripley wrote the Hirshhorn’s director to say that Gordon Bunshaft had approved of the new design and “felt that Mr. Collins’ assessment of the space proportions and the planting was very sensitive and well thought out.” Bunshaft had also told Ripley that he “hoped that the materials used in the ramp and the facing thereto would consist of the same kind of aggregate concrete work which occurs in the main building” (emphasis added), to which Ripley had replied that he believed it to be the case.

The National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), the District of Columbia State Historic Preservation Officer, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, and the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts had also reviewed Collins’ plan. In correspondence with the NCPC, Phillip Reiss, director of the Smithsonian’s Office of Planning and Engineering Services, noted that the garden redesign “will occasion no adverse effect to either environmental or historical characteristics now extant in this Mall area.”

As Collins’ plan was being executed throughout 1979 and 1980, further correspondences between the museum and the Office of Horticulture evince tension about acquiring planting materials according to exact specifications. Hirshhorn curator Joe Shannon told his colleagues in that office that “no contracts are to be let, or purchases made without Mr. Collins and/or myself viewing the individual plants.” In a subsequent memo dated February 7, 1979, Shannon further advised that after meeting with Director Lerner and others, “it was communicated to me in the strongest possible terms that they unanimously feel that the choice of specific trees for the Hirshhorn Garden is one that should be made by the Museum itself and not as a consequence of Federal purchasing procedures…trees were likened to art works in terms of distinctive shapes and particular foliage.” He continued, “These plants are integral to the design which Lester Collins prepared for the Museum and it is the Museum’s decision to follow his design in the reconstruction of the garden.”

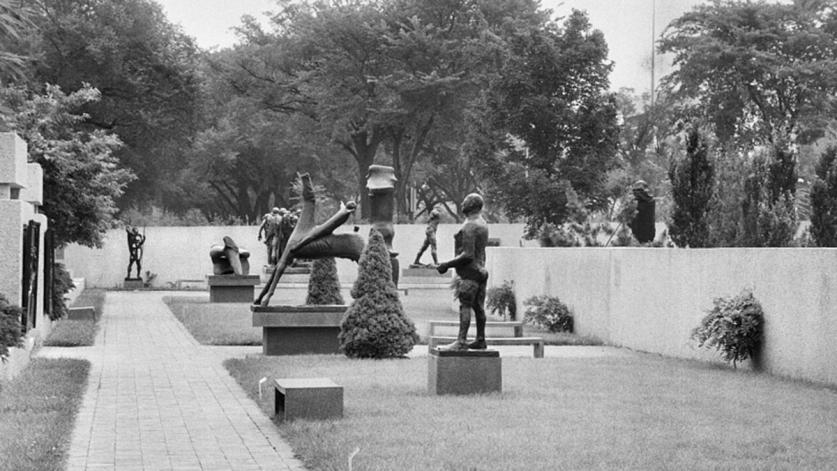

To accomplish the redesign, all of the sculptures were removed from the garden, the landscape was re-excavated, and additional infrastructure for both water and electricity was installed. Collins transformed what had been called a “desert-like expanse” into a shaded, choreographed journey through an urban oasis. Predating the 1991 American Disabilities Act (ADA) Standards for Accessible Design by more than a decade, the redesign afforded every visitor a dignified arrival and a comparable spatial experience. While the lateral stairs to the south were retained, Collins introduced ramps along the Mall side. Bordered by spreading English yew and screened from the Mall by trees, the textured, concrete ramps overlooking the garden gave visitors an initial glimpse of the reflective pool before pivoting to descend into the space.

The garden’s circulation system and display areas were clearly defined, greatly increasing its capacity for sculpture. The walkways encouraged users to circumambulate the works of art, which were set upon precast shelves against generous swathes of lawn and white gumpo azaleas. Bunshaft’s reflecting pool remained in its original form, and a concrete retaining wall formed the backdrop for the lower level, accessible by a ramp to the east and a stair to west. Collins chose trees that were heavily sculptural in form (as Shannon’s memo had indicated), including Babylon weeping willows, copper beeches, weeping beeches, ginkgos, Japanese black pines, cherry, and dawn redwood trees.

The Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden reopened in the fall of 1981 to critical acclaim. Washington Post architecture critic Benjamin Forgey wrote:

The new design reinforces the identity of the garden as a welcoming urban park…. [This] park for art…serves the sculpture. The divisions of the space prove essential accents; artworks pop in and out of view as the spectator moves about the space.

Forgey summarized the virtues of the Collins redesign again in 1993:

Working with an unusually tight budget of less than $600,000, Collins managed to introduce ramps for wheelchair access and otherwise to reinforce and improve the Bunshaft plan with walkways, trees, low plantings and panels of grass.

Well after the opening of the garden, the museum continued to assert the importance of properly maintaining Collins' landscape. In a memo written on March 11, 1982—clearly amid a dispute—the museum's executive officer, Nancy Kirkpatrick, issued a stern warning to the Smithsonian's Office of Horticulture that, despite tightening budgets, the garden was still to be well maintained.

The Sculpture Garden, integral to the Museum's mission, is the only garden specifically referred to in any public law pertaining to the Smithsonian Institution (P.L 89-788 "to provide for the establishment of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Museum Sculpture Garden, and for other purposes.") It is not a by-product or an afterthought; and the very name of our museum indicates its importance.