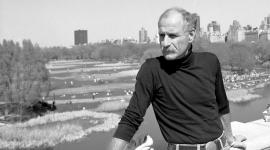

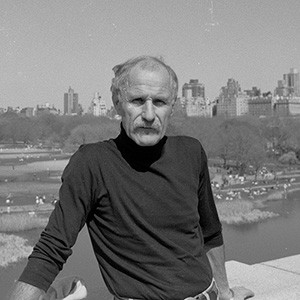

M. Paul Friedberg Biography

M. Paul Friedberg was born in 1931 in New York City. He spent much of his youth in rural Pennsylvania and Middletown, New York. When his father became a weekend landscape contractor and established a nursery business, the teenage Friedberg actively assisted.

After finishing high school, he studied ornamental horticulture in the agriculture school at Cornell University. College proved a formative experience for Friedberg. He took classes he took in the liberal arts department and met worldly colleagues and faculty, who introduced him to classical music, history and art. Despite this intellectual awakening and at his father’s behest, Friedberg intended to pursue a career in horticulture after graduation. He moved to New York City and instead found work in architecture and landscape architecture offices. His assignments were mundane, and his limited drafting abilities were quickly revealed, but during this time Friedberg gained valuable experience and a familiarity with prevailing urban park planning processes. Most importantly, he began to develop an interest in design.

In 1958, after two years outfitting city parks with stock features in standard configurations, he established his own practice, M. Paul Friedberg and Associates. It was fortuitous timing. Landscape architecture was just emerging as a distinct, professionalized field. A small group of pioneers including Lawrence Halprin, Robert Zion, Garrett Eckbo, and Dan Kiley were opening landscape design to modern ideas and exploring new forms of public spaces. It was clear that urban open spaces needed help. Cast aside by postwar suburbanization, the urban environment was increasingly considered threatening, dehumanizing, and in hopeless decline. Public parks and playgrounds were regarded as escapes from the malevolent city, but their designs were often unresponsive to the users' needs, if not hostile and coercive.

Bound by convention and bureaucracy, Friedberg's early work was unexceptional. Yet he was increasingly aware of the disconnect between public spaces and public needs and was increasingly frustrated by the waste, thoughtless inertia, and condescension that seemed to characterize the process of public landscape design.

In 1963 Friedberg's firm was hired to remodel the outdoor areas surrounding Carver Houses, a public housing project in New York City. They removed chain link fences, asphalt, and the standard playground pieces and introduced a spray pool and sandbox and a few other modest changes. It was a tentative step beyond typical playground form. Two subsequent public housing playground projects showed how varying gradients and topography contributed to exciting play places, and provided insights into appropriate ways of integrating modular manufactured playground pieces into more dynamic environments.

Thanks to a private grant, Friedberg was free to combine these new approaches with his first "total play environment" at Jacob Riis Houses in Manhattan's Lower East Side. Opened in 1965, it featured a series of experiences—a tree house, mounds, a tunnel—made primarily of granite block and separated by changes in the landscape. Paths, slides, and swings linked the various features within a unified landscape, the boundaries of which were delineated not by fences, but by changes in materials and other tactile and visual cues.

Riis Plaza was a watershed event. It was widely publicized (even appearing in Life magazine) and made the thirty-four year old Friedberg an instant expert. Riis Plaza and his other playground designs were distinct from other play spaces because they were not composed of isolated play features that could only be used in one way, by one child, from one age group, at a time. His playgrounds and their linked experiences, shifting grades and points of prominence and seclusion, provided opportunities for discovery, experimentation, exploration, creativity, and cooperation. Friedberg's empirical approach—studying his past work to identify successful and failed elements, and observing how landscapes are used—gave voice to the user and enabled him to design play places that met the needs of those users.

With these projects Friedberg’s reputation as a preeminent designer of urban play areas was firmly established. He furthered this expertise with publications. His 1970 book, Play and Interplay criticized the existing play area design process that provided isolated facilities without acknowledging or understanding the intended users “true needs, habits, nature, and desires” and without appreciation for the larger urban environment. It called for a “new recreation” in which the design of multifaceted play areas was integrated with education, housing, commerce, and transportation planning. In 1975, Friedberg published Handcrafted Playgrounds: Designs You Can Build Yourself. The book illustrated how amateur builders could construct customized play facilities with simple materials. By linking together assemblies of stacked timbers, nets, poles, tire swings, and drums designers can produce stimulating play areas that were adaptable to different age groups, lot sizes, and budgets.

Friedberg also became a leading designer of new public spaces including diminutive vest-pocket parks, municipal and corporate plazas and main street malls. The 1972 A.C. Nielsen headquarters near Chicago, though a suburban setting, included early versions of features that became central to his public space design vocabulary. The primary landscape element was a retaining pond with a plan characterized by right angles. Small islands, one connected to the shore by bridges, complicated the pond's shape and accommodated additional plantings. Ringed by paths and benches, the pond was set into the site and emphasized with sloping terraces above. Changes in grade screened the parking lot and introduced variety to the otherwise flat site.

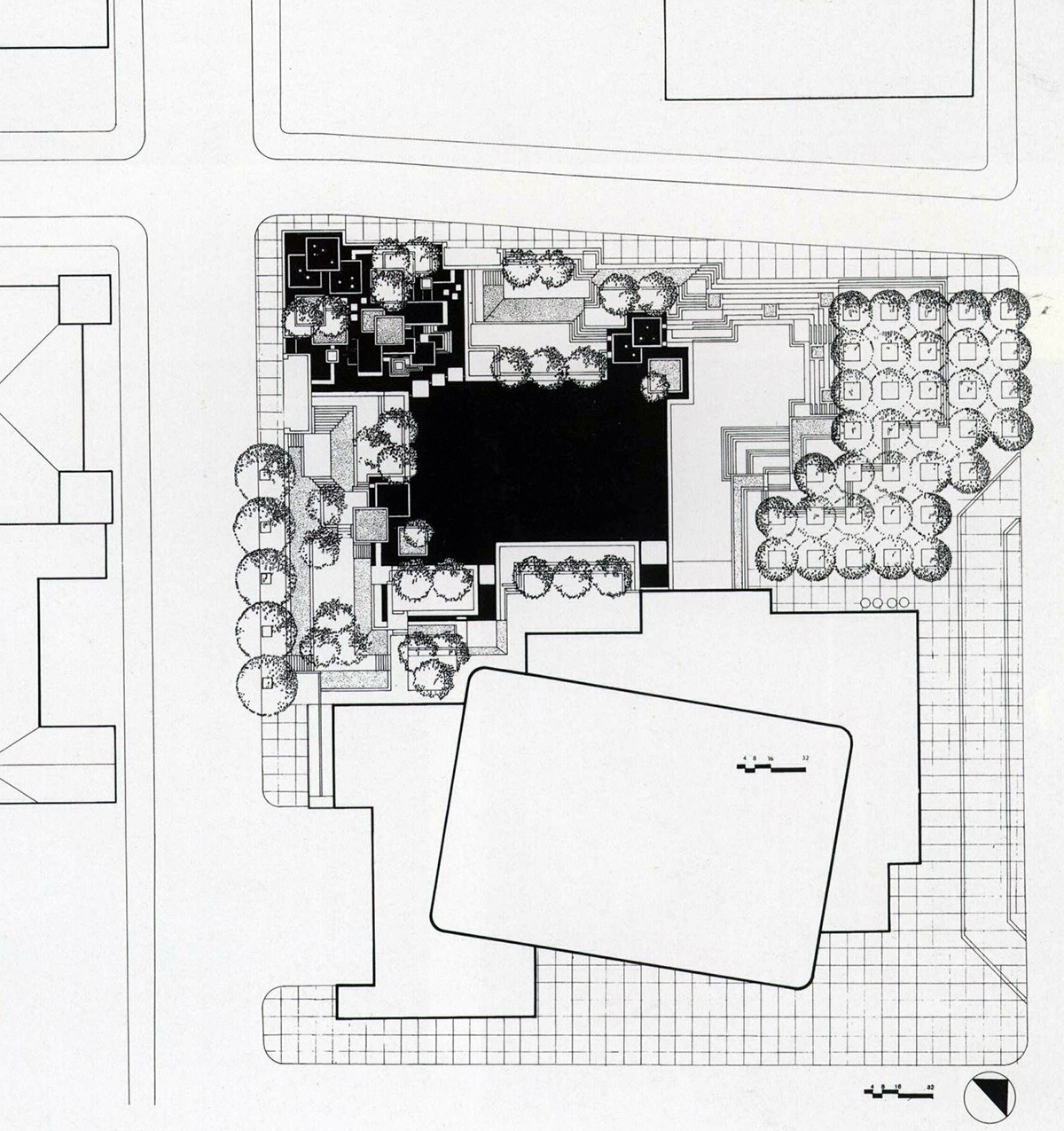

Subsequent designs in the 1970s and 80s, like Peavey Plaza in downtown Minneapolis and the Fulton County Government Plaza in Atlanta, Georgia, showed Friedberg adapting and reworking these elements. Paths and bridges interspersed among pools, ponds and water courses immersed visitors in the landscape. To encourage year-round use, Pershing Park in Washington D.C. (1981), and Calgary's Olympic Plaza (1987) both featured pools that were converted to ice rinks in the winter. This flexibility was carried over from earlier playground work as well as Friedberg's continued observations of what made public spaces successful. Also in common with his designs for play areas was the interconnection of park features as a means to encourage discovery and initiate an active engagement with the environment.

Friedberg has proven adept at making the most of the city's vertical nature. His 1982 Park Place is set above a parking garage. In 1989 he retrofitted a six acre rooftop plaza for New York's Fordham University, (1998) converting the space to a lush campus green. The design featured a large lawn area, amphitheater, ornamental plant displays, strategically placed outdoor sculpture, and a connected entrance and seating area for the school's dining facility. Friedberg's playground at Yerba Buena Gardens (1998) atop San Francisco’s convention center, remained true to his established approach to play area design. It is a three-dimensional linked environment where play features, from sandboxes to a maze, are joined with slides, stairs, paths, catwalks, and tunnels. A sundial, learning garden and a mural inscribed with measurements, emphasize experiential education as a component of play. The result: a continuous flow of play, exploration, and revelation.

Friedberg's later work illustrates his varied talents and convictions. Battery Park City (1998) on Manhattan's southern tip represents his continued interest in fostering public-private partnerships. Holon Park in Holon, Israel (1996), Queens Square, Japan (1999) and DLF Cyber Hub, India (2014) mixes contemporary recreational activities (entertainment and shopping) with public urban spaces. The Hascoe Residence in Greenwich, Connecticut and the Promenade Classique in Alexandria, Virginia (1990) were collaborations with other artists. La Jolla Commons in San Diego, California and Andromeda Houses in Jaffa, Israel, show Friedberg's philosophy of linked experiences and multi-use spaces applied to private housing developments that blend with the surrounding public environment.

Friedberg served on the faculty at Harvard University, Columbia University, Pratt Institute, and other universities. Recognizing the need to educate a new generation of professionals, he founded the Urban Landscape Architecture Program at the City College of New York in 1970. He was the director of the department, the first of its kind in the country, for the next twenty years.

Numerous awards confirm Friedberg's contribution to the field of landscape architecture and the design of urban public spaces. In 1979 he was made a fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects. The following year, the American Institute of Architects recognized Friedberg’s efforts to integrate the design work of various disciplines and presented him with the AIA Medal for an allied professional. Ball State University conferred a Doctorate of Laws on him in 1983, and in 1984 France awarded him the Chevalier de L'Ordre des Arts et de Lettres. In 2004 he received the American Society of Landscape Architect's (ASLA) Design Medal, and in 2015 the ASLA Medal, the organization's highest honor. Additionally Friedberg's individual designs have received 85 national and international awards.

Friedberg remained active at his firm M. Paul Friedberg and Partners (now MPFP) well into the 2010s. His career was one that questioned established conventions. His designs replaced fences and signs with spaces that were open to the broader urban environment and open to a multiplicity of uses. Friedberg's varied landscapes accommodated the differing recreational desires of children, adolescents, adults, and the elderly, providing independent spaces that still allowed encounters, exchange, and observation. They countered the city's image as a lonely and unnatural place. His designs were not set apart as refuges from the city but enmeshed within it. They engaged the theatrics of urban life and were unapologetically vital and active. Friedberg's legacy shares a common conviction: that designed landscapes can enhance life by revealing beauty in the environment and in human contact. M. Paul Friedberg passed away in New York City on February 15, 2025.

Bibliography

Friedberg, M. Paul and Ellen Perry Berkeley. Play and Interplay: A Manifesto for New Design in Urban Recreational Environment. The Macmillan Company, New York, 1970. Practical design solutions for all age groups from children to the elderly. Many Friedberg design projects are richly illustrated with extensive black and white photography.

Friedberg, M. Paul. Process 82. M. Paul Friedberg: Landscape Design. Process Architecture Publishing Company, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, 1989. Includes probing essays by Jonathan Barnett and William H. Whyte* that places Friedberg’s work in context. Chronological survey of critical projects beginning with Riis Park Plaza in 1965 through the 1980s.

Bennett, Paul. M. Paul Friedberg: Social Force, Projects 1988-2000. LandForum 08, Spacemaker Press, Palace Press International, 1999. Chronological survey of late work. Includes an introductory essay that places this work in context by Bennett and an editorial by Peter Walker. Concludes with current projects. Richly illustrated.

About the Author

Chad Randl is an architectural historian and author of the 2004 book A-frame. Updated on February 17, 2025 by Charles A. Birnbaum.