Making and Taking: 2015’s Notable Developments in Landscape Architecture

For broken, derelict, and underutilized urban space, 2015 was a good year. In North American cities, including Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Toronto, and elsewhere, landscape architects contributed to the ‘urban renaissance’ through excellent design, thoughtful urban planning, and prescient environmental management. Ambitious waterfront-development projects are generating headlines and car-obsessed cities are developing pedestrian-centric solutions. This is an exciting period of connecting and rethinking; however, it is also a period marred by taking—specifically, the confiscation of open space held in the public trust, including parkland designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. Here’s a look back at what happened and what’s worth following.

Connecting

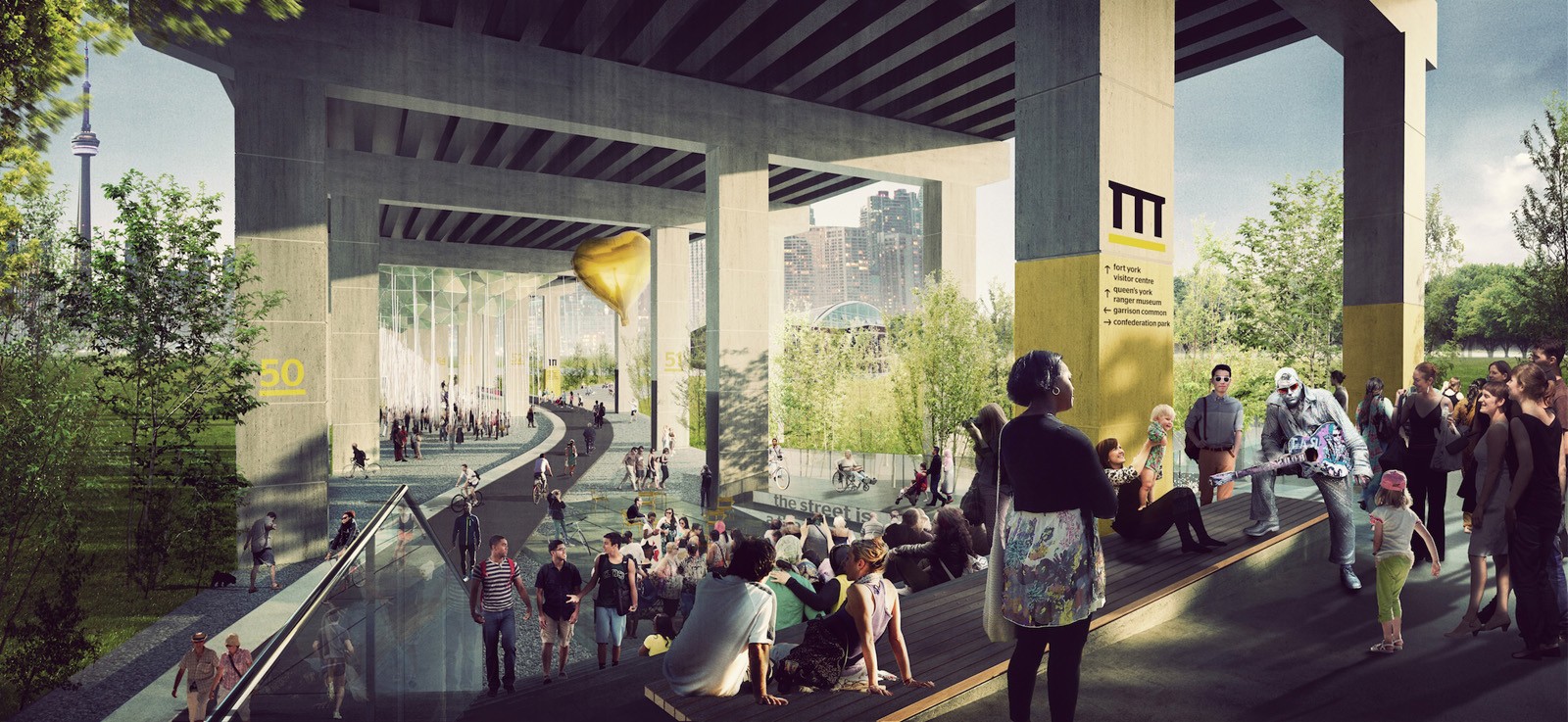

Toronto continues to impress with new additions to world-class development on its waterfront. In addition, a recently announced proposal to build a linear park beneath a portion of the Gardiner Expressway has been widely lauded, and Evergreen Brick Works aspires to “brand” the city’s network of ravines—The Ribbon at the Lower Don—in the tradition of Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace in Boston. Meanwhile, another nexus of truly ambitious design, as I wrote last year, can be found in Houston, where Buffalo Bayou Park, designed by the SWA Group, recently opened. This exquisite synthesis of design, remediation, flood control, and environmental management is part of an extraordinary investment in the public realm (to be explored during a conference and weekend of free tours presented by TCLF on March 11-13, 2016), which would not have been possible without strong and supportive civic leadership and private philanthropy.

Phase two of Chicago's dramatic Riverwalk opened this past summer, with spaces designed by Sasaki Associates, Ross Barnet Architects, Alfred Benesch Engineers, and Jacobs/Ryan Associates, and Maggie Daley Park, designed by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, opened immediately adjacent to Millennium Park (these new sites were teeming with activity when I visited last month). Another significant addition, the Bloomingdale Trail (another Van Valkenburgh design), also known as The 606, was created from a 2.7-mile stretch of former rail line (nearly twice the length of New York City’s High Line), thanks to a public-private partnership among the City of Chicago, the Chicago Parks District, and the Trust for Public Land.

In other waterfront news, half of the new 9.5-acre Festival Pier site in Philadelphia will be set aside for public space designed by OLIN, while in California, an eye-catching, headline-making, and somewhat controversial proposal would convert 51 miles along the Los Angeles River into parks, trails, and mixed-use development. For the ne plus ultra of car-obsessed cities, this would be a monumental change; however, there are a multitude of environmental and financial concerns, and the secret designation of architect Frank Gehry as the designer and a lack of public input have drawn criticism, according to news reports.

Rethinking

Earlier this year, New York City’s new Department of Parks and Recreation Commissioner Mitch Silver gave me a preview of an intriguing new initiative called “Parks Without Borders.” As detailed in the Atlantic’s CityLab, Silver proposes the reduction in height (and/or the elimination) of fencing, along with the addition of benches, tables, and other amenities, all to reduce physical and psychological barriers to the parks, and to make them more welcoming and better integrated with their neighborhoods. In a similar vein, the National Park Service (NPS), known for iconic wilderness parks like Yosemite and the Grand Canyon, is implementing its "Urban Agenda," an effort to create greater public engagement and awareness of its rich collection of urban parks as part of its centennial celebration in 2016. Like Commissioner Silver, NPS officials want to make the parks more welcoming.

Taking

Sadly, there is also a frustrating and growing national trend in parks today: land held in public trust is being confiscated for new construction projects. This is especially troubling when viable alternatives exist. Chicagoans and the rest of the country are waiting to see which of the city’s two historic Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr./Calvert Vaux-designed parks will see the amputation of some twenty acres to accommodate the Obama Presidential Library (one of them, Washington Park, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places). Meanwhile, legal hurdles are being thrown in the way of the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, which would be built along the lakefront (the present site is a parking lot, which, on the surface, makes the museum proposal seem palatable; however, it’s protected by the public trust doctrine that prevents development of the site). In New Jersey, a sports complex has been proposed for Rahway River Park, an Olmsted Brothers design that is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places and is part of a larger ensemble of important parks. And, an eight-acre portion of New Orleans’ City Park, which reflects a design from the 1920s, largely by the firm Bennett, Parsons and Frost of Chicago, is being carved off for the Louisiana Children's Museum Early Learning Village.

Pershing Redux

Meanwhile, the fate of parks named Pershing in Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles is up in the air. Five finalist designs for a national World War I Memorial on Pennsylvania Avenue in the nation’s capital would demolish one of the most significant extant works by landscape architect M. Paul Friedberg. The designs were recently presented to the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, which has approval authority over the project. Several of the commissioners voiced concern, with one suggesting that perhaps the design-competition jury shouldn’t have chosen any of the finalists. The approval of other agencies is required, so the final impact on the Friedberg design has yet to be determined. In Los Angeles, however, the days seem to be numbered for the postmodernist Pershing Square designed by Hanna/Olin and architect Ricardo Legorreta. Will a tabula rasa approach be the only acceptable solution for both of these early postmodernist projects?

Naming

Another controversy brewing in the Chicago area concerns Jens Jensen Park, named for the Danish-born landscape architect who created the Prairie Style of landscape architecture found in some of the city’s great parks. Amid claims that Jensen (1860-1951) made racist statements, there are calls to rename the park. But questions have been raised about whether Jensen’s remarks have been cherry-picked, thus obscuring the broader and very democratic nature of his legacy.

Interpreting

Given the innate ephemerality of landscape architecture, scholarship is vitally important. Three (of many) significant books were published this year: Frederick Law Olmsted: Plans and Views of Public Parks, edited by Charles Beveridge, Lauren Meier, and Irene Mills, with its unrivaled collection of Olmsted plans, is an invaluable reference; Women, Modernity, and Landscape Architecture, edited by Sonja Dümpelmann and John Beardsley, lifts the veil on leading female modernists around the globe; and The Landscape Architecture of Richard Haag: From Modern Space to Urban Ecological Design, by Thaisa Way, is the first serious biography of one of the most influential practitioners for multiple generations of landscape architects.

Passing

Finally, 2015 saw the untimely and sudden passing of Peter Lindsay Schaudt, one of the most honored and beloved practitioners of his generation. After graduating Harvard he worked with Dan Kiley before settling in Chicago, where he set up his own firm, later known as Hoerr Schaudt Landscape Architects. His prolific career was characterized by a “dignity of restraint” and reverence for the works of his predecessors, an enlightened and inspiring model for stewardship.

This article first appeared in the Huffington Post on December 3, 2015.