The NAOP Gives Historical Context on Jackson Park

Editor’s Note: The following letter was written by representatives of the National Association for Olmsted Parks (NAOP) and submitted to the American Society of Landscape Architects blog “The Dirt” on January 26, 2018. The letter is in response to an article by Jared Green, published on January 23 in “The Dirt,” and to an article by Blair Kamin on January 22 in the Chicago Tribune. Those articles both dealt, to some degree, with questions about the Olmsted-era designs for Jackson Park and, most importantly, the extent to which the park exhibits the intent of those designs today. In addition to the NAOP’s response, three other documents are appended below, each of which speaks to these same questions. Co-author Arleyn Levee is a member of TCLF's Stewardship Council and was a founding member of TCLF's Board.

January 26, 2018

Dear Mr. Green:

Responding to your article - "The Case for the Obama Presidential Center in Jackson Park" - in “The Dirt” of January 23, 2018 (subsequently updated at least five times), we would like to make the following observations:

1. While the video embedded in this article with former President Obama articulating the very noble aims for his Presidential Center (OPC) is indeed inspiring, unfortunately it fails to address the very fundamental question: Why does such a multi-dimensional institution HAVE TO BE located on historic parkland dedicated in perpetuity to open space and recreational opportunities for all?

As many others have pointed out, there are certainly other land holdings within the bounds of Chicago's South Side, some even abutting the historic South Park complex, that would equally meet or exceed the requirements for such an elevated architectural campus intended as the beacon of change, education, and rejuvenation for the city. And as some 200 University of Chicago faculty have pointed out in their open letter, other South Side locations are demonstrably better locations to benefit from the "economic engine" that the OPC promises to be. For all the skilled planners engaged in this endeavor, successfully weaving this campus and its ancillary needs, such as parking, into the fabric of the South Side without the present “parkland grab” would seem a challenge worthy of their talents.

2. We take issue with several of Mr. Van Valkenburgh's assertions concerning the Olmsted & Vaux and the Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot planning for what became Jackson Park.

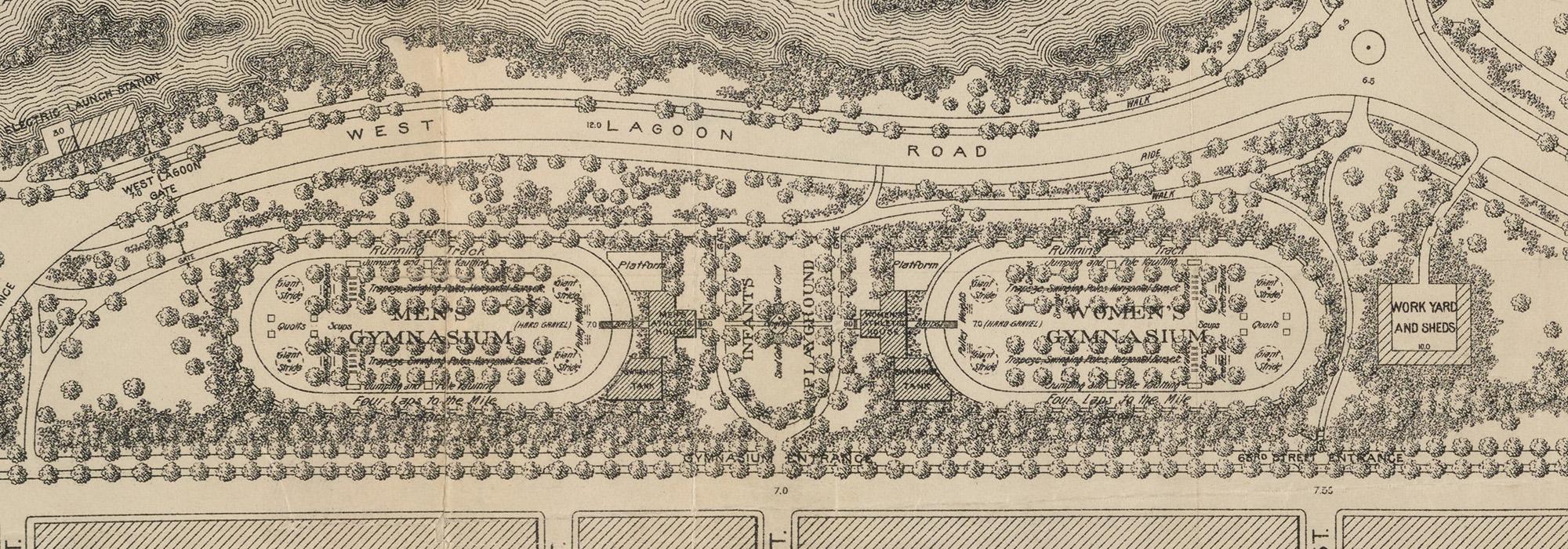

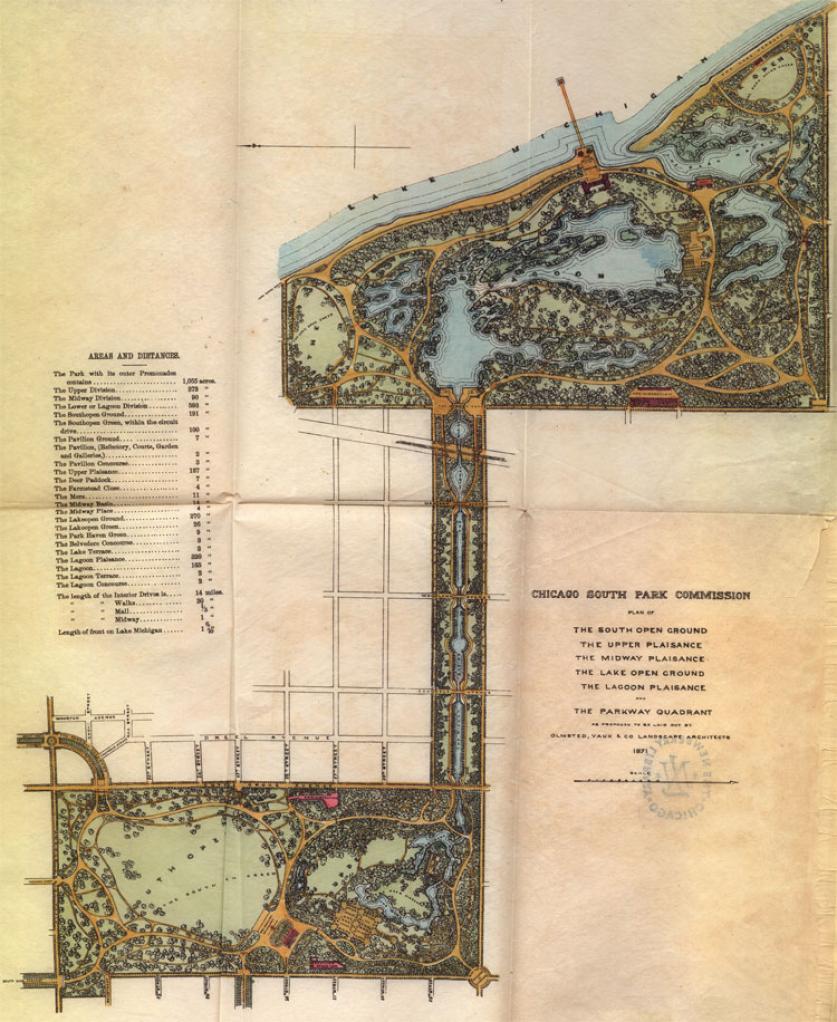

In the first place, asserting that the original 1871 plan was never fully realized due to the economic woes besetting Chicago after the 1871 fire does nothing to negate that the Olmsted and Vaux plan was thoughtfully crafted to bring elements of nature into this originally swampy venue, with its scenic lakeside potential to benefit the health and the spirits of the hard-working citizenry in a rapidly industrializing city.

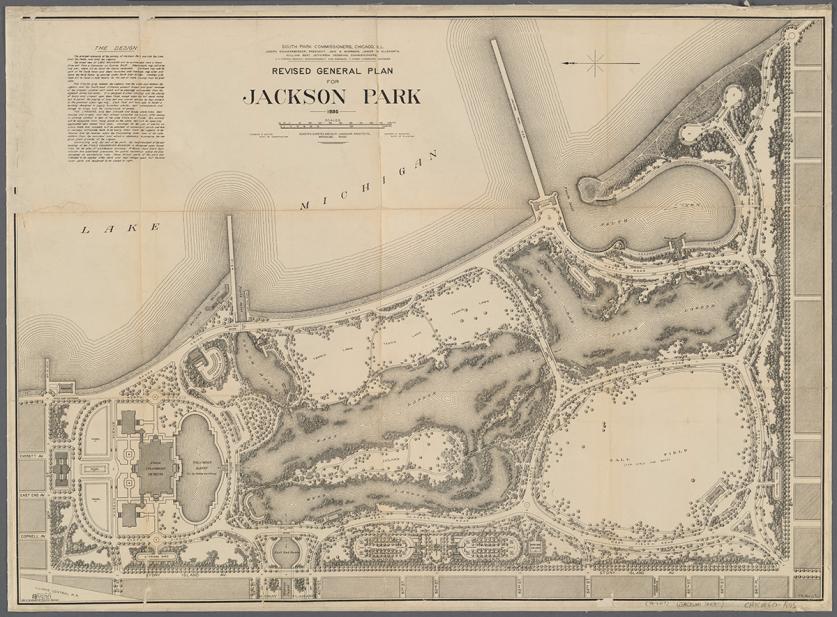

Second, as Mr. Van Valkenburgh well knows, as someone who considers himself a student of Olmsted's philosophy and work, the “White City of 1893” was greatly tempered by the green, scenic ameliorations that Olmsted insisted upon to counteract its Beaux-Arts grandeur. Knowing the Olmsted firm's working methods, it is to be expected that the planning concepts developed for the Exposition would also contain those ideas to remediate the site, once the temporary plastered edifices constructed for the Exposition were removed, to bring back parkland intended for public use. That this intention was slow to be accomplished was due to the national economic recession in the years following 1893. But the ideas for what became the 1895 plan by the Olmsted firm were undoubtedly embedded in that process.

Third, as with all great design offices, of which the Olmsted firm was the first, there were many hands and minds in collaboration, creating and refining such major commissions as the Exposition planning and the subsequent park redesign. John Charles Olmsted, a partner in the firm, worked alongside his father and his colleague and partner, Henry Codman, from the outset to bring forth the ingenious landscape solutions for the Exposition and for the future of the site. Indeed, the younger Olmsted was the recipient of an Exposition medal at the successful completion of the event. Charles Eliot entered the firm as a partner in 1893 following the untimely death of Codman, thus forming the Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot firm. (The assertion that this successor firm was headed by Olmsted’s “sons" is quite inaccurate, as Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., was still a student at Harvard at this time.) That the name was changed to reflect the retirement of Olmsted, Sr., in no way indicated a reduction of design and intellectual rigor at the helm of the firm. The senior Olmsted continued to be a creative force, even as he was plagued by the ill health that brought about his retirement in mid-1895; but his partners were well versed (and trained) in his aesthetic principles and sustained the integrity of his vision of comprehensive design into what became a remarkably long-lived professional practice. The succeeding partners likewise continued Olmsted, Sr.’s innovative planning, responsive to the diverse demands of Chicago’s and the nation’s changing populations.