Neglected Heritage Beneath Our Feet: Documenting Historic Street and Sidewalk Pavement Across America

What defines the modern city? For many, towering skyscrapers would be an obvious answer, having been synonymous with modernity since the 1880s. Yet contemporaneous with the rise of skyscrapers was the much less heralded, but just as significant, revolution that took place under people’s feet with the development of permanent sidewalks, curbs, and street paving.

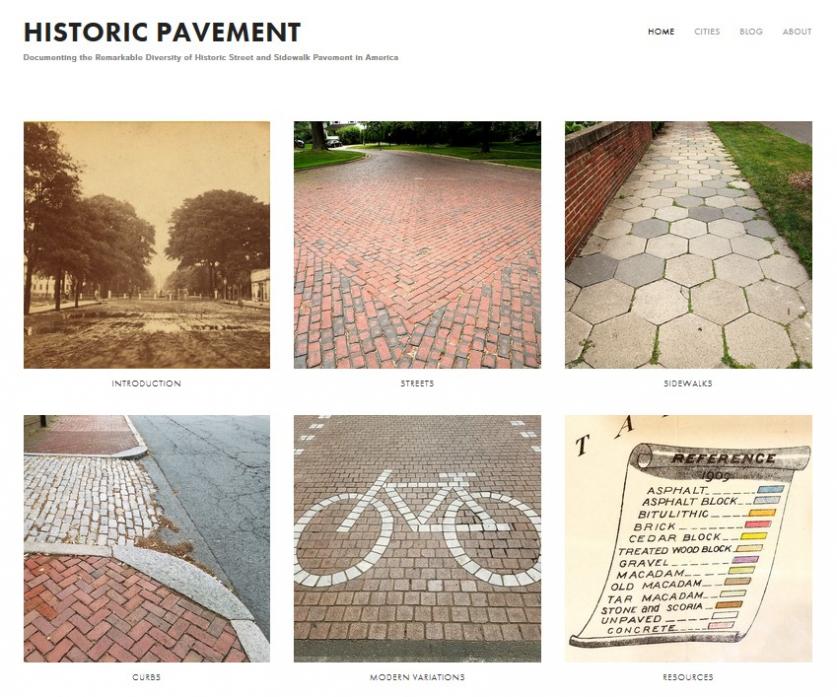

While historic buildings have enjoyed the attention of preservation professionals for decades, the landscapes that are part of their physical setting have largely gone unprotected and undesignated, and are vulnerable to the whims of less sensitive decision makers. In Savannah, where the preservation community has successfully saved or designated thousands of buildings within multiple neighborhoods, the street and sidewalk pavement (and even the city’s celebrated squares and other green spaces) survive without formal designation or protection. In the past few years, sections of five streets have seen their pavement removed or covered with asphalt, including the removal of historic cobblestones from one of the ramps on the city’s waterfront. It is concern for the fate of Savannah’s remarkable pavements that resulted into an ongoing national study and the launch of a dedicated new website, entitled Historic Pavement. Launched in July 2016, the website documents examples of diverse street and sidewalk pavement types, embedded features (such as street signs and commercial advertisements), and curbs, as well as developing city profiles.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, cities across North America experimented with a wide variety of materials with which to pave city sidewalks and streets. The installation of street pavement, along with water supply, sewers, street railways, and parks, advanced the idea of the modern city. In an environment where pavement is often vilified as the antithesis of ecological and sustainable urbanism, it is hard to appreciate how essential street pavement was to improving the quality of life, health, and safety of cities. Prior to the development of inexpensive modern asphalt in the 1920s, cities struggled to find affordable, durable, and available types of pavement suitable to their needs. Pavement was inherently local, with each city devising its own solution to the challenge of paving streets- resulting in unique regional paving “fingerprints.” The varying degrees to which historic pavements survive in cities further enhances this sense of identity.

In researching the evolution of historic street pavement in Savannah, where a variety of pavements and patterns survive, it became clear that the available scholarship on pavement made no mention of the localized solutions to the challenge of pavement in the nineteenth century. The absence of such information inspired the efforts behind Historic Pavement, along with a goal to visit as many cities as possible in order to document representative examples of what survives and locate historic records that could shed light on each city’s pavement history. To date, twenty cities have been visited, revealing an astonishing variety of surviving pavement, and - as revealed in archival documents- historic efforts to find successful pavement solutions.

The earliest pavement in American cities – cobblestones – survives in historic port towns along the eastern seaboard, such as Boston, Alexandria, Charleston, and Savannah. But many other early materials used for pavement have long since disappeared, including sandstone blocks, pyrites, and oyster shells, the latter utilized mainly in Southern cities. Wood blocks were among the most widely used early paving materials, with some cities like Detroit utilizing them for most of their paved streets by 1899. Yet nationwide only a handful of streets preserve this material, including Wooden Alley in Chicago- a rare example of a street that has attained historic designation and protection. One of the most unusual materials encountered is in Philadelphia: iron slag bricks (otherwise called scoria), a blue pavement that resembles glazed ceramic.

Successor pavements, mainly granite Belgian blocks and vitrified brick, proved durable, and were relatively smooth and widely available. Not surprisingly, they survive to a far greater extent. It is easy to equate their broad use with uniformity, but a comparison of these materials from multiple cities reveals a rich variety of material, size, shape, color, texture, and laying pattern. How and where cities utilized these materials varied immensely, with some cities paving all the streets in a district (German Village in Columbus, Ohio, for example), while others focused only on parallel streets (such as the brick streets in Baltimore). These patterns – as they survive – are being surveyed and plotted in Google maps. A few are displayed in the “Cities” section of the Historic Pavement website, and more will be added over time.

Sidewalk pavement and curbing exhibit even greater regional variety. While granite is the most common historic curbing material, slate, sandstone, schist, marble, and metal (sometimes featuring stamped patterns) are also found. Sidewalks possessed and retain the greatest material and design variety. New York and Philadelphia feature monolithic slabs of granite spanning the width of the sidewalk, with some sporting hand-chiseled textures. In New Orleans, terrazzo sidewalks allowed shop owners and restauranteurs to attract attention through elaborate designs, including images of giant oysters. While asphalt, and to a lesser extent concrete, replaced earlier forms of street pavement, sidewalks have continued to evolve after World War II, with popular hexagonal pavers akin to mid-century-modern buildings.

And, just when you might think you can wrap your head around all of this, you come to realize that the emergence of reproduction pseudo-historic pavements as part of the broader historic preservation movement has further complicated the material history of many cities’ streets.

Robin B. Williams, Ph.D., chairs the architectural history department at the Savannah College of Art and Design. Historic Pavement can be visited at historicpavement.com.