New Permanent Buildings Proposed for Seattle's Freeway Park

The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) has been involved with Freeway Park, a masterwork by landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, since 2006 when the park, “one of the most compelling treatises on post-War landscape architecture that survives today,” was enrolled in the foundation’s nascent Landslide program.

Since then, TCLF has served as a consulting party in the Section 106 review process, per a programmatic agreement in 2018, supported the site’s listing in the National Register of Historic Places (2019), and designation as a City of Seattle Landmark (2022), included the site in the acclaimed traveling photographic and digital exhibition The Landscape Architecture of Lawrence Halprin (ongoing since 2016), multiple publications, a Pioneers oral history with Halprin (2010) that includes Freeway Park, and other advocacy initiatives.

An important part of the 2018 programmatic agreement states that the City of Seattle would follow federal guidelines “with solicited advisory input from TCLF and other consulting parties, for any proposed project that has potential to affect Freeway Park’s character-defining features as defined in the NRHP nomination of the park.” (emphasis added).

Well, that didn’t exactly happen.

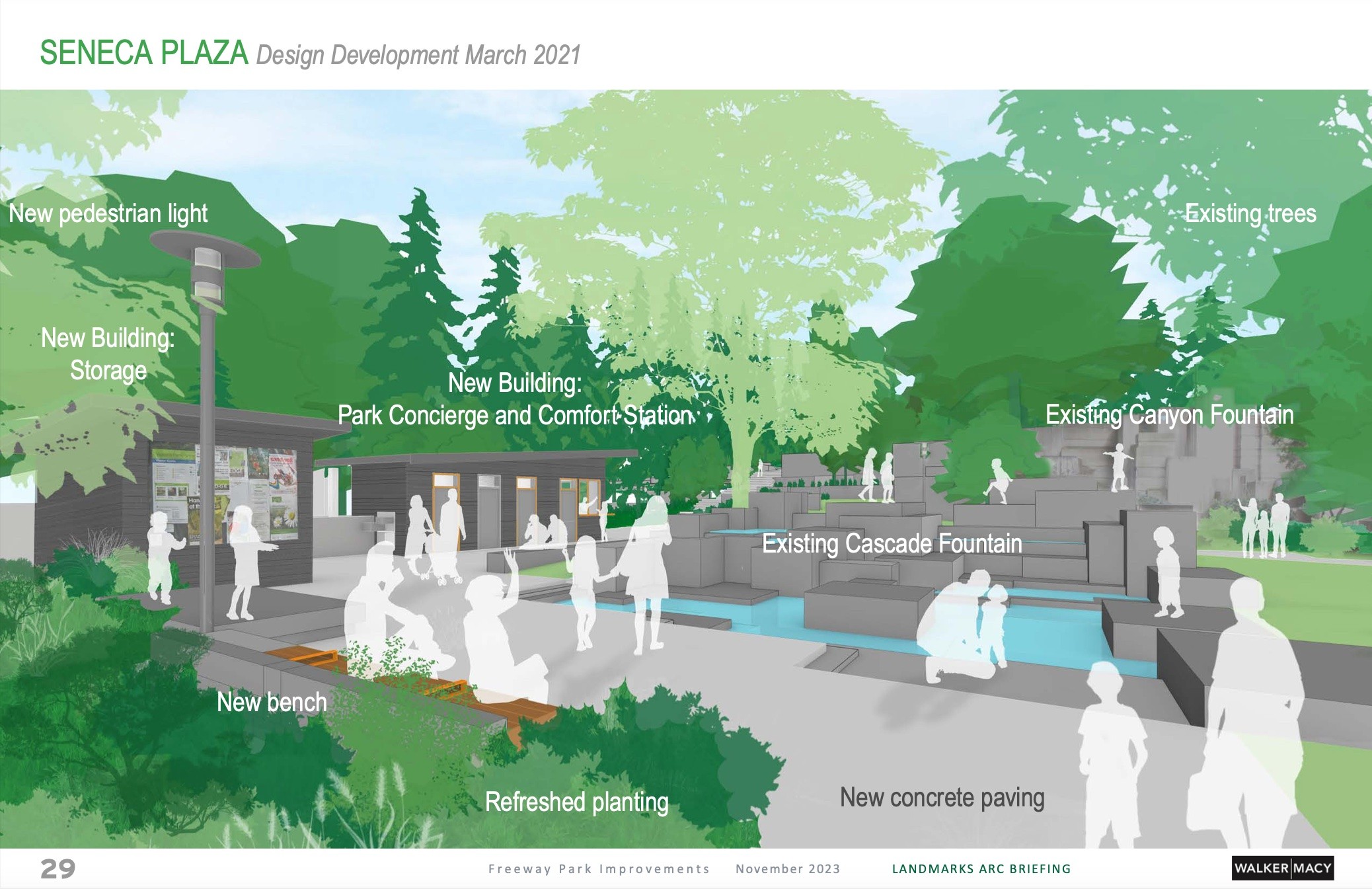

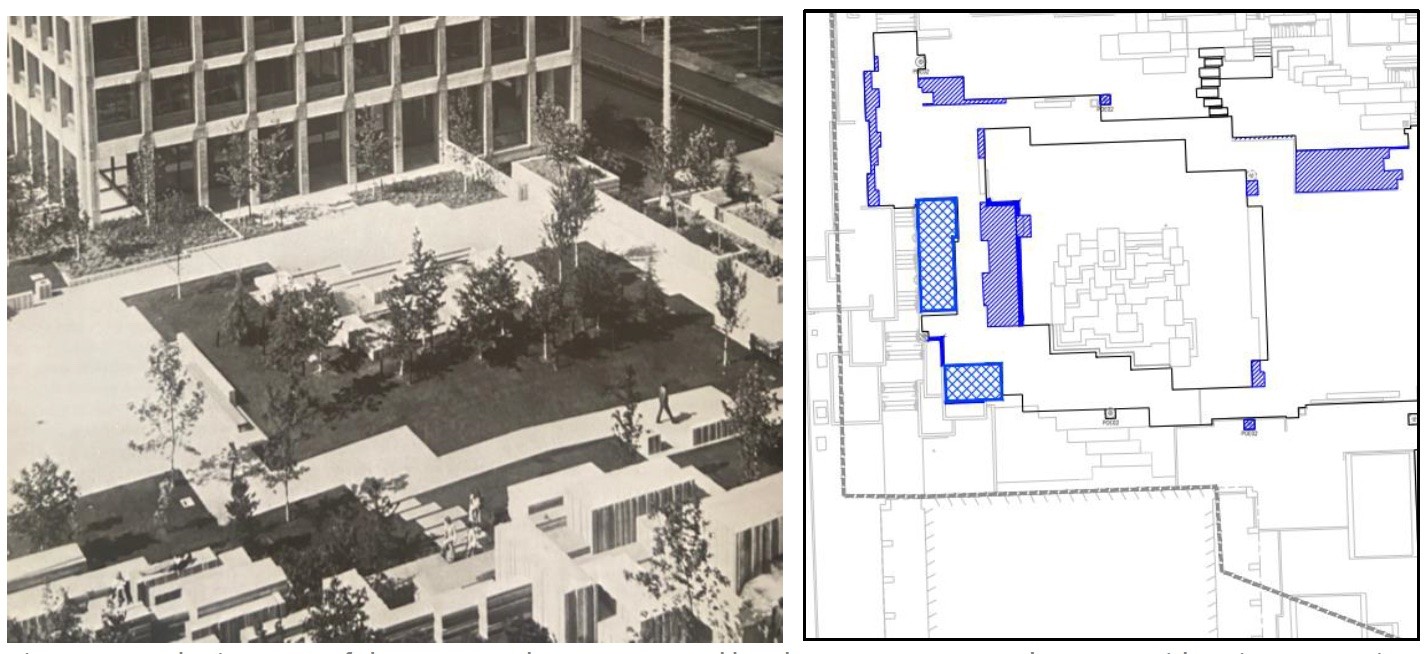

In fact, without notifying TCLF and several other consulting parties, the city advanced proposals to rehabilitate the park – much of it good. However, and most consequentially, the proposal would insert new permanent structures – a restroom/“concierge” and storage facilities – into Seneca Plaza (see above) a significant contributing space in the park’s overall National Register-designated design.

These additions would radically alter and negatively impact Halpin’s design intent for the plaza (see above), which welcomes visitors and establishes Halprin’s visual and spatial language for the park that follows.

But more on that shortly.

First, some context. Freeway Park, which opened in 1976, was a daring and innovative response to the newly built Interstate 5, which, in the 1960s, had cleaved Seattle’s downtown from the First Hill neighborhood, virtually cutting the city in two. As the NRHP nomination noted, “The park was not only a victory over the nation’s growing freeway system,” it also “served as an example of the power of public involvement in urban planning.”

Although Freeway Park has suffered from deferred maintenance in recent decades, its design integrity is much intact. Occupying more than five acres as it stretches over the interstate, the park is defined by a series of irregular, linked plazas enclosed by board-formed concrete planting containers and walls. The separate areas achieve consistency and cohesion through a limited materials palette of concrete, broadleaf evergreen plantings, and subordinated site furnishings, while the spaces are distinguished and animated with bold water features. Significantly, the National Register nomination noted the full range of the park’s character-defining elements, from its fountains, paths, and plazas to its light standards, benches, trash receptacles, and its board-formed concrete finish.

Five years ago in January 2019 Seattle Parks and Recreation (SPR) issued a Request for Qualifications (RFQ) to select a design team to carry out the $10 million Freeway Park Improvement Project, which includes $9,250,000 for parkland capital improvements and $750,000 for activation. TCLF’s last engagement with Freeway Park, other than supporting the 2022 landmark effort, was in October 2019 at Seattle’s Town Hall when TCLF was invited to participate in an open house hosted by the city. That engagement also included a site walk and in-office meeting with city officials and their landscape architecture consultants.

Fast forward to May 2024 when TCLF learned via a Google alert that a review process had been advancing all along, but that TCLF and other consulting parties had not been apprised, as required by the 2018 programmatic agreement. As recounted in a November 24, 2024 letter from TCLF to Rhys Harrington, Senior Capital Project Coordinator at Seattle Parks and Recreation, this began a frustrating months long effort to get information about the project, which had reached the 60% design development stage, and to meet with city officials with oversight of the project. By the time of TCLF’s November 24, 2024 letter, the project was advancing to 90% design development stage, which meant a great many decisions were being finalized including the construction of the multiple bathroom/“concierge” facility and a storage facility that would have an adverse effect on the character-defining Seneca Plaza (the panoramic image below shows the areas to the left of the fountain where the new permanent structures would be built).

In a follow-up letter on December 13, 2024, TCLF provided a detailed critique about the proposed additions to Seneca Plaza that also included this observation: "[T]he “Seneca Plaza Design Approach,” ... makes no mention of the critical visual and spatial relationships that contribute to the landscape’s significance. Instead, the primary focus is on a collection of new insertions that fundamentally diminish the landscape’s historic character. The absence of any mention of visual and spatial relationships, the foundational and most important criteria for analyzing and understanding a cultural landscape, is a fundamental flaw in how the design was developed and how it is now being assessed." (emphasis in the original).

Fortunately, appeals to officials at the Federal Highway Administration and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, who were unaware that the affected consulting parties had been excluded from the review process, have paused the project. A new Memorandum of Agreement will be drafted to include all affected consulting parties before any reviews commence.

This story is not over ... watch this space for the next update.