Newport Discoveries: A Rare Christopher Tunnard Garden Reappears

The opening of this two-day excursion began with an overview lecture by John Tschirch, who introduced us to the estates and gardens of Newport, and the work of the Preservation Society by a dedicated and concerned group of Newporters originally under the leadership of its founders, Katherine and George Warren.

Much to my surprise, although I had visited many of Newport’s Gilded Age estates along its celebrated Cliff Walk over the past decades, and was familiar with the important and comprehensive Meservey Survey that the Society undertook in 1947, I was unaware of Katherine Warren’s interest in Modernism – in fact one may suggest that Mrs. Warren’s Profession – straddling both historic preservation and design was new territory. Yet, on Friday morning in John’s slide show I would soon connect the dots – Warren’s own early Federal style house would soon provide a monumental eureka moment: this intimate walled garden was the very one that appears on page 80-81 of Peter Shepheard’s Modern Gardens: Masterworks of International Garden Architecture (Frederick A. Praeger, New York, 1954) under the title, “Newport, Rhode Island, U.S.A. Christopher Tunnard, 1949.”

Much has been written about Christopher Tunnard (1910-1979), yet it appears that this nationally significant, rare, surviving garden – perhaps the only extant American commission by the man who influenced many of our most celebrated post war architects (e.g. Philip Johnson) and landscape architects Se.g. Lawrence Halprin) was forgotten. For example, in the essay, “Christopher Tunnard: The Garden in Modern Landscape,” (Modern Landscape Architecture; A Critical Review, Marc Treib editor, 1993) author Lance Neckar makes no mention of this garden suggesting that “building on his Harvard and Gropius connections, he [Tunnard] executed a small number of residential gardens in the Cambridge and Lincoln areas of Massachusetts.” (p. 153)

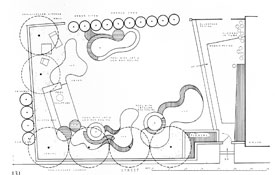

Shepheard describes the garden as “65 feet by 42 feet, though it has a hint of luxury in its fountains, its thick hedges and its sculpture, has an extreme austerity of design very different from Tunnard’s early work in England. The sinuous pattern and the asymmetrical placing of the sculpture are to some extent informal, but this is not the formality of growing plants breaking up architectural geometry—the plants themselves are cut and trimmed into an ordained shape. The pattern is, of course, designed to be seen from the ground, where its curves interlock and turn back on themselves.”

By Saturday afternoon we had gained access and were eager to go with a copy of Tunnard’s plan [below center] in hand. Swinging open the double doors to the rear garden, we were greeted by a copy of the Jean Arp sculpture, “chimerical font”-- still on axis -- immediately bringing to mind the Villa Noailles at Hyeres, France, by Gabriel Guvrekian (with its own focal sculpture by Lipschitz) published in Tunnard’s own influential treatise, Gardens in the Modern Landscape (1938) [below right].

|

|

|

Stepping down into the garden, much to my amazement, it was all still there – the stone terrace that meets the central lawn at an obtuse angle; the four water features (two circular, one biomorphic and one black lacquered rectangular pool housing the golden bronze Arp); and, the perimeter tree plantings (Arborvitae for enclosure to the right, and to the left and opposite, five of the six original pleached Lindens with crushed gravel below anchoring a concealed perimeter walk). A raised planter met the terrace, originally planted with annual blooming flowers. Although the tightly clipped shrubs and vines are all still present, (the original box, yew and ivy), they are now overgrown, unfortunately concealing the small water features and encroaching into formerly open spaces. Finally, the perimeter walls, originally exposed white painted block much like the French Villa, were now completely covered with Boston ivy, significantly altering the figure ground relationship. As Dorothee Imbert has noted, gardens such as Villa Noailles “were less paintings, less sculptures, less architectural space than bas-relief—compositions that barely got off the ground and into the third dimension.” It is for this reason that one wishes the return the contrasting white walls.

Back in Washington, the discovery of the forgotten Tunnard garden had me reflecting on the issue of value – the ca. 1810 Federal Style residence was protected, yet the Tunnard garden was not designated – even though its significance in landscape architecture is greater than the individual building.

on to the cliff walk...

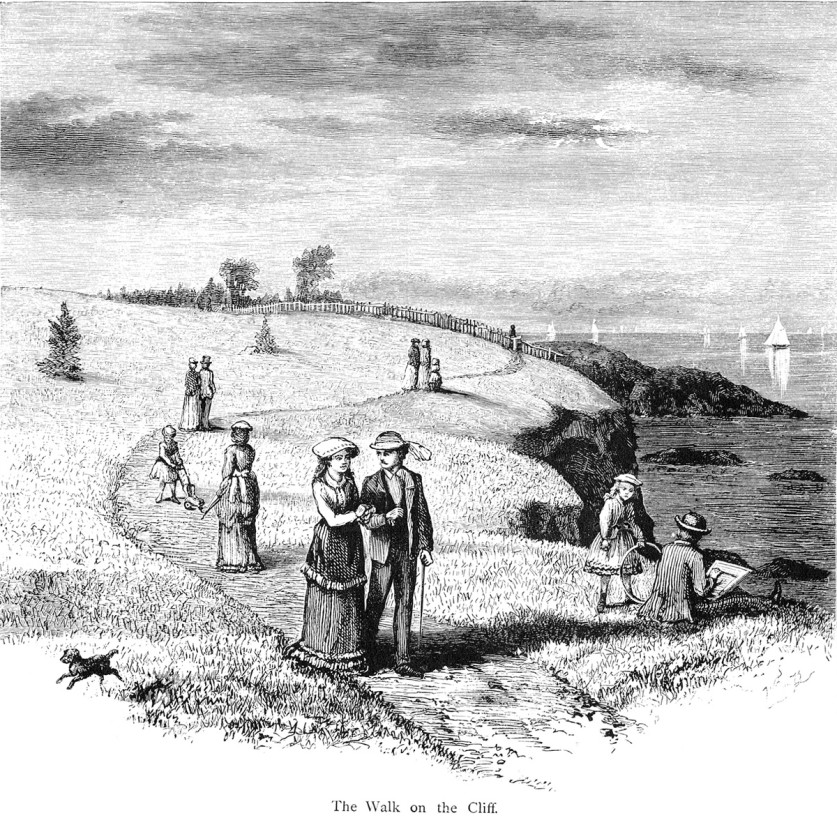

Perhaps Newport is like many other places when it comes to attributing value to the historic designed landscape – beyond mere beauty. As I walked along the Cliff Walk, passing a great number of National Historic Landmarks (e.g. The Breakers and Marble House) along a National Historic District set within a 3.5 mile designated National Recreation Trail (1975), I find myself wondering why the Cliff Walk is not recognized as a pioneering civic masterwork, a National Historic Landmark with significance in Landscape Architecture?

What is truly known about this linear walk whose very alignment is thought to have been first established by deer, with significant development following from the 1880s to the late 1920s?

A website dedicated to Cliff Walk suggests that the pedestrian amenity “was protected by the combination of long term public use, the ‘Fisherman's Rights’ granted by the Colonial Charter of King Charles II, and a passage in the Rhode Island Constitution that granted the public ‘rights of fishery and the privileges of the shore to which they have heretofore been entitled.’ Now centuries of prior use have guaranteed the legal right of people to walk on the cliffs.”

Even Tunnard himself in The City of Man: Architecture-City Planning-Public Art (1953) suggests a context statement of significance for Cliff Walk [image from publication left], noting that “The chief virtues of this first period of suburbs were its close interlocking of planning, architecture and gardening, its rich invention, its breaking of the gridiron pattern by substituting the romantic plan, and its real concern with art in shaping the environment. Looking at the average present-day suburb one can see the difference. Central Park was an innovation; Riverside the beginning of a great middle class exodus; even the Cliff Walk at Newport which ran around great estates was a symptom that times were changing and that communities were becoming interdependent. Newport was not Versailles. Even on the Hudson people were now able to buy their farms instead of leasing them from landowners. . . But the country as a whole could not ignore it, and in the planning that went on toward the turn of the century the knowledge that all Americans had a stake in their communities was a constantly growing reminder to developers that gestures in this direction must be made.” (p. 202-203)

So what can we do today to expand the value placed on the authentic landscape heritage of Newport?

When Mrs. Warren passed away in 1976 the Society had 200 employees and six properties. Today the Newport mansions attract one million annual visitors, have 362 employees (during peak season) with 11 owned by the Society. Even some of the mansion grounds, such as The Elms, are being restored. Yet, the only two designations with significance in Landscape Architecture in Newport are the Ocean Drive Historic District (designated in 1976) and the Newport Casino NHL (designated in 1987).

What would Christopher Tunnard and Mrs. Warren have to say about this today?

Tunnard shared Mrs. Warren’s interest in historic preservation. Lance Neckar notes in Modern Landscape Architecture that “by the 1970s Tunnard was a well-known activist in historic preservation circles in New Haven, Connecticut—where he was a founder of the local landmarks commission.” (p.154) He was also one of the progenitors of the Venice Charter, the founding document of the International Commission of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS).

Neckar in his biographical profile of Tunnard in Pioneers of American Landscape Design (2000, p.398) notes that by the time of Tunnard’s death he came “full circle to be identified with conservation- and preservation-oriented attributes toward city revitalization which were antithetical to the modern movement.” Perhaps one day in the future the rare surviving Tunnard garden and the pioneering Cliff Walk, much celebrated by Tunnard, will be elevated in stature to join the small list of 60 or so National Historic Landmarks in Landscape Architecture in America.