Church and Eckbo: A Houston Perspective

Liese House, Lloyd & Morgan architects, Thomas Church landscape architect, 1954, demolished. All images courtesy the author.

During the late 1940s through the early 1950s, Modernism seemed poised to become the new paradigm for design in Houston. Today this unique regional legacy is being rediscovered.

In April 1952, New York architect Philip Johnson was in Houston for the opening of an architectural exhibition and tour of modern houses sponsored by the Contemporary Arts Museum. He was interviewed for the Houston Chronicle where he declared: “Texas are too modest. There are more modern homes here than in all Europe…Here where the pioneer spirit still flourishes and people aren’t afraid of new things there is good soil, climate and lots of space in which to set the trend in contemporary architecture.” During a critical period from the late 1940s through the early 1950s, Modernism seemed poised to become the new paradigm for design in Houston. Not only were all important cultural and commercial buildings of this period modern, but so were the all the significant houses, many of which were published in the local and national press. A large percentage of these architect-designed houses were complete works of design with separately credited interior designers and landscape architects.

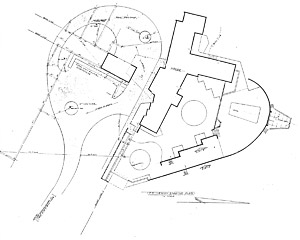

Straus House, Lloyd & Morgan architects, Thomas Church landscape architect, 1951, demolished.

C. C. Pat Fleming’s sensational landscape design for architect Hugo Neuhaus’s house of 1950 inaugurated the parade of postwar modern gardens in Houston. Shortly thereafter Houston clients began to commission modern landscapes from the nationally known offices of Thomas Church and Garrett Eckbo of San Francisco, then at the height of their popularity. The works of Thomas Church in particular seem to have had a lasting impression. One of Houston’s most prolific landscape architects, Fred Buxton, who was educated at Texas A&M and began his practice in 1956, was later hired by several of these same homeowners to make changes to Church’s original designs. Other important landscape architects of this period included Bishop & Walker, Edward Courtade, James Darymple, Ralph Ellis Gunn, Ruth London, Hugh Pickford, Charles Tapely, and Robert F. White.

Straus House

Houston in this period was the most cosmopolitan of the major Texas cities. As it outgrew its provincial origins, it was concerned with the present, not the past. There was no regional school of architectural and landscape design as there was in Dallas or San Antonio. Houston clients were nearly as likely to hire a nationally known landscape architect as they were one of the many local practitioners. And the work of its own designers reflected this modern, cosmopolitan vision as they looked beyond Texas for their inspiration.

Although sometimes the only information we have left is the landscape architect’s name, patient searching has unearthed a trove of materials from photos to plans, and sometimes original, intact gardens. Sadly, too few of these private utopias still exist. They live on, however, in dusty files and fading photographs, a vision of modesty and ecological sensitivity that is compelling for it both its ecumenical spirit and its local inflections—traits today that remain as pertinent as they were fifty years ago.

Editor’s Note: This feature is being presented in conjunction with the upcoming Pioneers Regional Symposium, Landscapes for Living: Post War Years in Texas.