Ocean Park Neighborhood Beach: The Significance of the "Inkwell" in Jim Crow-Era Southern California

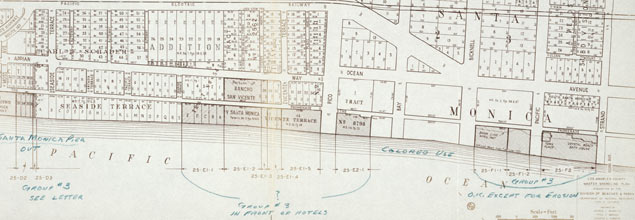

The 'Colored Use' beach is called out on this 1947 shoreline map; photo courtesy University of Southern California Library Special Collections.

*This feature was created for What's Out There Weekend Los Angeles, held on October 26th and 27th, 2013. Learn more about weekend tours and events.

In the early 1900s a two-block area of Pacific oceanfront in Santa Monica, stretching from the western end of Pico Boulevard to Bicknell Street, became a popular gathering place for African Americans and remained so through the mid-twentieth century. The Anglo community denigrated the site by calling it the “Inkwell” in reference to the skin color of the beachgoers, but the very people it was intended to impugn adopted the name as a badge of pride.

The beach was situated near the Ocean Park neighborhood and Phillips Chapel Christian Methodist Episcopal (CME) Church, founded in 1905 as the first black church in Santa Monica, which also anchored an early African American settlement around 4th and Bay Streets. During the high season, hundreds of African Americans from throughout Southern California socialized, enjoyed the ocean breezes and swam at the Inkwell because they experienced less racial harassment there than at other area beaches.

Verna Williams and Arthur Lewis at the Jim Crow era, African American

beach site (derogatorily called the "Inkwell") in Santa Monica, California,

1924. Los Angeles Public Library Online Collection

California had laws from as early as the 1890s about public beach access for all citizens, but sometimes those laws were not acknowledged by Whites. There were unfortunate personal assaults on individual African Americans to inhibit their freedom at public beaches north and south of Santa Monica. By 1927, as a result of legal challenges led by the National Association of Colored People (NAACP), the California Courts upheld the laws put in place from 1893 to 1923 that provided equal access to any public beach in the state.

By the mid-1920s exclusive beach clubs began to open near the foot of Pico Boulevard, pushing the Inkwell beach site south towards Bay and Bicknell Streets. At the same time, the Santa Monica Bay Protective League blocked the development efforts of an African American investment group, the Ocean Frontage Syndicate, led by Norman O. Houston and Charles S. Darden, Esq., with plans to build a first-class resort with beach access where Shutters Hotel is located today. Pushed southward by the exclusive clubs from which they were restricted and simultaneously denied their own club, the Black community’s presence continued at the Ocean Park neighborhood beach, a comparatively safe haven from discrimination and harassment.

As social and legal barriers began to crumble from 1948 to 1968, with the overturning of restrictive real estate covenants and the prohibition of most forms of discrimination, sites of African American leisure activity began to fade away. No longer a segregated space today, the Inkwell beach site includes the California Wash art installation and Crescent Bay Park. In 2008 the City of Santa Monica erected a monument at Bay Street and Oceanfront Walk officially recognizing the historic significance of the area and the early African American community there, including the first documented surfer of African and Mexican American descent, Nick Gabaldón (1927–1951).