Pioneering Swedish Women Garden Designers c. 1900-1950s

Ulla Bodorff, the sun bathing area at the roof garden at The Swedish Cooperative Union’s head office in central Stockholm, designed in the 1940s.

One hundred years ago, there were few women working professionally with garden design, yet today, the majority of the Swedish landscape architect students are women. This remarkable change within the profession has happened largely in silence. Even the historic contributions of the groundbreaking women of the early 20th century have been sublimated within the consciousness of the field.

Largely unknown even to experts on garden history today, about a dozen women established themselves within the field between 1900 and 1950, some of whom became very successful. With the research project “Women Garden Designers in Sweden 1900–1950: Toward a Professional Identity” I aim to highlight their innovations and spur renewed interest in their contributions. While their individual careers are of importance, I have chosen to study them as a group, which gives me opportunity to compare and analyse their training, methods of working, types of commissions, and writings, etc. It is my hope that the investigation will be a contribution to the larger discourse around women artists, photographers, and academicians.

When studying women garden designers, their education and training is crucial. It is the beginning of a working career, and a way to distinguish professionals from amateurs (though the latter group is of interest too.) Several Swedish garden schools admitted women, but required several years of practical experience prior, which could be difficult to obtain. Around 1900, several garden schools for women only opened, but these mainly aimed at teaching women to maintain their own gardens, or to educate children in gardening. In this educational context, the majority of the early (those established between 1900 and 1950) Swedish women garden designers were trained abroad.

(top) Ruth Brandberg with Selma Lagerlof; (bottom) Villa garden of the architect Cyrillus Johansson, designed in collaboration with Helfrid Löfquist

Some chose the Horticultural College for Women at Swanley, Kent, UK, where they took longer or shorter courses, sometimes resulting in a General Horticultural Certificate. Others, like Inger Wedborn (1911-1969) travelled to Germany where she studied at the influential Heinrich Wiebking-Jürgensmann at Institut für Gartengestaltung at Berlin-Dahlem in the 1930s, followed by a period at Alwin Seifert’s office working on landscape conservation during the construction of the Reichsautobahn. After returning to Sweden, Wedborn started to work for the landscape gardener Sven A. Hermelin, who soon promoted her to associate. For decades they directed a very successful office, which still exists. Many of the drawings leaving the office were signed “Sven A. Hermelin & Inger Wedborn, Stockholm”, but today most of their commissions are attributed to him only, an omission that diminishes the rich truth of the history of our gardens and designed landscapes.

Several women had practices of their own, most likely working alone in their homes, while others had employees. Collaborations with architects were common, and this might have given them access to the offices’ facilities. In the beginning of the century, private commissions dominated, mainly villa or manor gardens. Some women, like Ruth Brandberg (1878–1944) and Helfrid Löfquist (1895–1972), also designed numerous hospital parks and institution gardens. Only few of these have survived. Löfquist's most extensive commission was the Sidsjön hospital park, which included different types of housing with gardens for the staff, all in a hierarchic way with villas for the physicians, town houses for the married, and apartments for the unmarried staff. In a presentation of the hospital, Löfquist emphasises that the physicians' gardens were made as one big park without any fences or borders between the grounds, after inspiration from contemporaneous American practices. From the 1920s, and especially in the 30s and 40s when the Swedish towns expanded and the country became more and more industrialised, residential areas became frequent commissions for all landscape designers in that period. Urban parks on the other hand, were rare as they were mainly designed within the towns’ parks departments, where women hardly ever were employed.

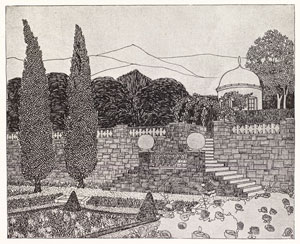

Ester Claesson, design for a terraced garden, published in Deutsche

Kunst und Dekoration in 1907, and in The Studio in 1912.

One of the most important figures in the first generation of professionally trained women was Ester Claesson (1884–1931). After taking a gardening exam in Denmark in 1903, she continued to travel abroad, first to Vienna, then to the artists’ colony Mathildenhöhe at Darmstadt in Germany, where she in 1905 became the pupil, and later co-worker, of the Austrian architect Joseph Maria Olbrich (1867–1908). Until recently, Ester Claesson’s outstanding position at Olbrich’s office has been totally unknown, but this was the beginning of a long and remarkable career. She was the only woman in the office, but as Olbrich's trusted associate, she worked with most of the garden commissions. For Olbrich, drawing was an important tool in the creative process. He obviously transferred his interest to her, and her drawings from this period show that she was a very skilled artist and highly capable of interpreting Olbrich's ideas. Claesson’s most important work at Mathildenhöhe was a terraced rose garden commissioned by one of Olbrich’s influential clients, Julius Glückert, the owner of a Darmstadt furniture factory, to accompany the house he used for displaying his furniture. This was much more than a private garden. It was the centre of the colony, connecting the large Ernst Ludwig Haus studio house at the colony's highest point with some of the exquisite villas below.

Ester Claesson returned to Sweden in 1913, leaving a position with the architect and cultural heritage preserver Paul Schulzte-Naumburg at his Saalecker Werstätten, briefly working for a well-renowned architect before opening her own office. Ester Claesson's importance, from a German as well as from a Swedish perspective, can't be underestimated. Only 23 years old, in 1907, she was published in Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration. In 1912, while still working in Germany, the British journal The Studio published 3 of her drawings. She was for many years a contributor to Gartenkunst, the leading German periodical. Through her, German garden design was introduced in Sweden, both through her many commissions as well as through her writings, in which she introduced Olbrich and Schultze-Naumburg to Swedish readers. Trademark features of her work are architectural elements and a formal garden style that stood in opposition to nineteenth century horticultural ideals.

Reimersholme residential area, central Stockholm, designed by Ulla Bodorff in the 1940s.

Ulla Bodorff (1913-1982) is a good example of a successful woman led office with several employees. In the 1930s, Bodorff acquired an academic degree from the University of Reading in England. After returning to Sweden, she worked for some years at the head gardener’s office in Stockholm, but soon opened her own office, which she ran until the 1970s. Among her commissions we find a number of People’s parks and residential areas all over the country. One rather spectacular commission involved a roof garden at The Swedish Cooperative Union’s head office in central Stockholm, which she designed in the 1940s. Here, the staff could sun bathe, relax, and play different games, all with a splendid view of the capital. One of her most renowned compositions, the Berthåga cemetery outside Uppsala, came as the result of a competition she won in 1961. Like Ester Claesson, Bodorff kept in touch with colleagues all over Europe, mainly through IFLA, in which she was active from its inception in 1948.

Through their commissions, writings, and lectures, as well as through participating in competitions and exhibitions, many Swedish women garden designers have contributed to the development and establishment of high level artistic landscape design, often in symbiosis with Swedish nature. Through their training and travels abroad, they brought to Sweden new ideas and perspectives on gardens and landscape design. Now it is their turn to be understood; it is time to write their biographies, care for their drawings and other archival material, and preserve their designed parks and gardens, and returned to their rightful place the canon of landscape designers.

Sites Accessible to the Public

Mårbacka in the county of Värmland, home of the author and Nobel Prize laureate in literature Selma Lagerlöf, garden by Ruth Brandberg c. 1910.

Sångs in the county of Dalarna, garden for the author and Nobel Prize laureate in literature Erik Axel Karlfeldt by Ester Claesson c. 1925.

Sidsjön hospital, Sundsvall, landscape planning by Helfrid Löfquist in the 1940s.

Park at the chocolate factory Marabou in Sundbyberg close to Stockholm, Sven A. Hermelin and Inger Wedborn, 1940s.

Reimersholme residential area, Stockholm, designed by Ulla Bodorff in the 1940s.

Berthåga cemetery, Uppsala by Ulla Bodorff, 1960s.

Biographical References

Jonstoij, Tove, "Ester Claesson 1884–1931", Svensk trädgårdskonst under fyrahundra år. Stockholm 2000.

Migge, Leberecht, ”Der Neue Hausgarten”, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration Heft 20, 1907.

Nolin, Catharina, "Ruth Brandberg 1878–1944", Svensk trädgårdskonst under fyrahundra år, Stockholm 2000.

Persson, Bengt, "Ulla Bodorff 1913–1982", Svensk trädgårdskonst under fyrahundra år, Stockholm 2000.

"Recent Design in Domestic Architecture", The Studio 1912.