For Sale: The Santa Barbara Residence of Noted Landscape Architect Lockwood de Forest

Could there be a more desirable listing for a real estate agent than the personal residence of a famous architect? If a building is truly a work of art, then its highest form must surely be revealed when the artist is unfettered by red tape and fickle clients. The homes that famous architects design for themselves are indeed a boon to the real estate market, and they are also low-hanging fruit for writers and for the compilers of the ubiquitous lists that have become the sifted fodder of our informational diets.

There are signs, however, that such cachet is no longer reserved for the “starchitects” alone, as the real estate market seems prepared to pay dollars-and-cents homage to homes associated with well-known landscape architects, too. In 2012 and 2013, a string of articles in Curbed reported on the sale of landscape architect Ellen Shipman’s home, and the online magazine also reminded its readers that Garrett Eckbo played an important part in designing the Brody House in California’s Holmby Hills, which fetched nearly $40 million from Ellen DeGeneres. What is purportedly the priciest home currently on the Richmond, Virginia, market boasts proudly of work by landscape architect Charles Gillette.

The Santa Barbara residence of Lockwood and Elizabeth de Forest may yet prove to be another case in point. But the impending sale of the property highlights the uncertain fate of the home and garden designed by one of the leading West Coast landscape architects of the early twentieth century.

Located on a private road just north of Mission Santa Barbara are the home and garden that landscape architect Lockwood de Forest III (known professionally as Lockwood de Forest, Jr.) designed in 1927 for himself and his wife, Elizabeth Kellam de Forest, who was also a landscape architect. His and his wife’s parents paid for the house and land, respectively, as wedding gifts to the young couple, whose first home was damaged in an earthquake two years earlier. The two adjacent lots that de Forest chose offered a pleasant microclimate and views of the majestic Santa Ynez Mountains, the narrow east-west range that forms a natural scenic backdrop to downtown Santa Barbara. While the innate beauty of the setting lends much to the property, it is de Forest’s design of the house and garden that makes it historically and culturally significant.

Born in 1896 in New York City, de Forest attended the Thacher School in Ojai, California, in 1912, where he arrived with considerable abilities as a painter and photographer and developed an interest in California landscapes. His father, Lockwood de Forest II, was a noted landscape painter and interior designer who had partnered for a time with Louis Comfort Tiffany. After one semester at Williams College and a summer course in landscape architecture at Harvard, the younger de Forest volunteered for service in World War I. After the war, he studied landscape architecture for a year at the University of California, Berkeley, in a program designed to give returning veterans experience in professional schools. In 1921 he undertook a study-tour of parks and gardens throughout England, Italy, France, and Spain before finally settling in the Santa Barbara area.

As a practicing landscape architect for nearly 30 years, de Forest helped establish the Mediterranean style in Southern California and define the aesthetics of West Coast landscape design in the early twentieth century. He and wife Elizabeth founded and edited the Santa Barbara Gardener, and from 1925 to 1942 they published the work of a range of authors, including Lester Rowntree, Lucille Council, and Florence Yoch. In addition to their regional sensitivity, de Forest’s landscapes are distinguished by their bold horticultural effects and use of asymmetry within formal settings. Perhaps his best-known design was that for Val Verde, the estate of Wright Ludington in Montecido, where de Forest transformed Bertram Goodhue’s austere architectural ensemble, replacing lawns with reflecting pools and using geometric form and plantings to create a dramatic setting for the owner’s notable sculpture collection. Along with other important commissions, such as the Casa del Herrero and renovations at Lotusland, de Forest consulted for many years on the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

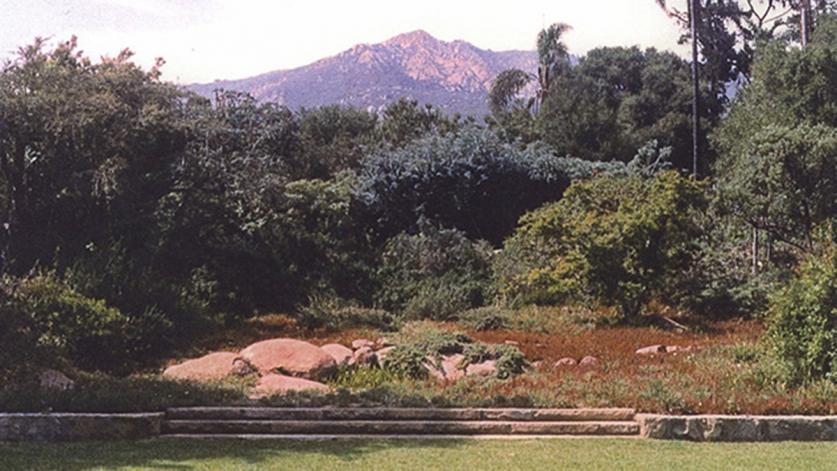

For his personal residence, de Forest fully integrated the design of the house with that of the garden, one of the earliest and clearest responses by a landscape architect to the indoor-outdoor lifestyle that the region’s climate could afford. The rather severe one-story home that de designed stood in stark contrast to the Spanish Colonial Revival houses that were popular in the area in the 1920s. De Forest placed the house at the center of the site, with each of its rooms planned to give access and views to the garden that surrounded it. The garden comprised four functional zones—entry, service, social, and recreational—and was divided into room-like spaces by an overriding geometry that became less obvious over time, as the maturing plantings softened the rigidity of its strong lines. Along with the drought-tolerant plantings that de Forest chose, perhaps the most resonant acknowledgement of the regional landscape was a square lawn defined by low walls and planted with resilient kikuyu grass. The lawn was never irrigated by the de Forests, who rather appreciated that it turned to beautiful hues of straw and saffron during summer, blending with the natural environment around it. The prospect north from the house was thus a golden lawn set before a rock garden and backed by the Santa Ynez Mountains. The road that would have otherwise interrupted that view was masterfully concealed by a low berm.

The impending sale of the de Forest property should cause us to think about the fate of the countless irreplaceable works of landscape architecture that remain in private hands. If landscape architecture is every bit as much an art as is architecture, as our leading cultural critics have begun to recognize, then there is cause for both hope and despair along Todos Santos Lane in Santa Barbara. For while the property has unfortunately been “upgraded” by the installation of an artificial turf lawn, most of de Forest’s design intent is still clearly legible. But with the property once again up for sale, it will now be up to the market to determine the worth of a masterpiece, and to ensure, perhaps, that any would-be purchaser will protect their investment by protecting the garden that makes the property unique and historically significant. Those who believe that de Forest’s design is worth preserving for its intrinsic value alone must therefore place their faith in something of a conundrum: they must hope that the free market, which operates on the assumption that nothing is priceless, will set a price high enough to preserve de Forest’s legacy.