Norfleet Giddings Bone Biography

Born in Gainesville, Texas, the son of Edward Everett and Maggie Norfleet Bone, Norfleet Giddings Bone (1892 - 1978) moved with his parents and three sisters to New Mexico soon after the start of the twentieth century. Upon completing prep school, Bone followed his father’s footsteps by studying civil engineering, earning a B.S. at New Mexico A & M College. His first job, in 1915, was as assistant city engineer of Douglas, Arizona, where he gained experience in city planning and designed sewage systems, roadways, and other municipal improvements.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Bone joined the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. As a second lieutenant, he served in the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe during 1918 and 1919. After his honorable discharge in 1920, he attended Texas A & M College, where he received his second degree, a B.S. in landscape architecture, in 1923. Bone studied with Professor F.W. “Fritz” Hensel, who chaired the Department of Landscape Art, and attracted the attention of professor of horticulture and landscape architect Nestor M. McGinnis. He accepted a position as a landscape architect and engineer with McGinnis & McGinnis in Dallas, Texas. In 1925 he married Ruby Lee Franklin and spent the summer studying advanced landscape design at the University of California, Berkeley, and landscape drawing and sketching at the School of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, California. The couple returned to Dallas, where Bone continued to study drawing and engaged in a varied landscape architecture and engineering practice that included among its projects country estates, city residences, university and school grounds, parks, and street-parking plans.

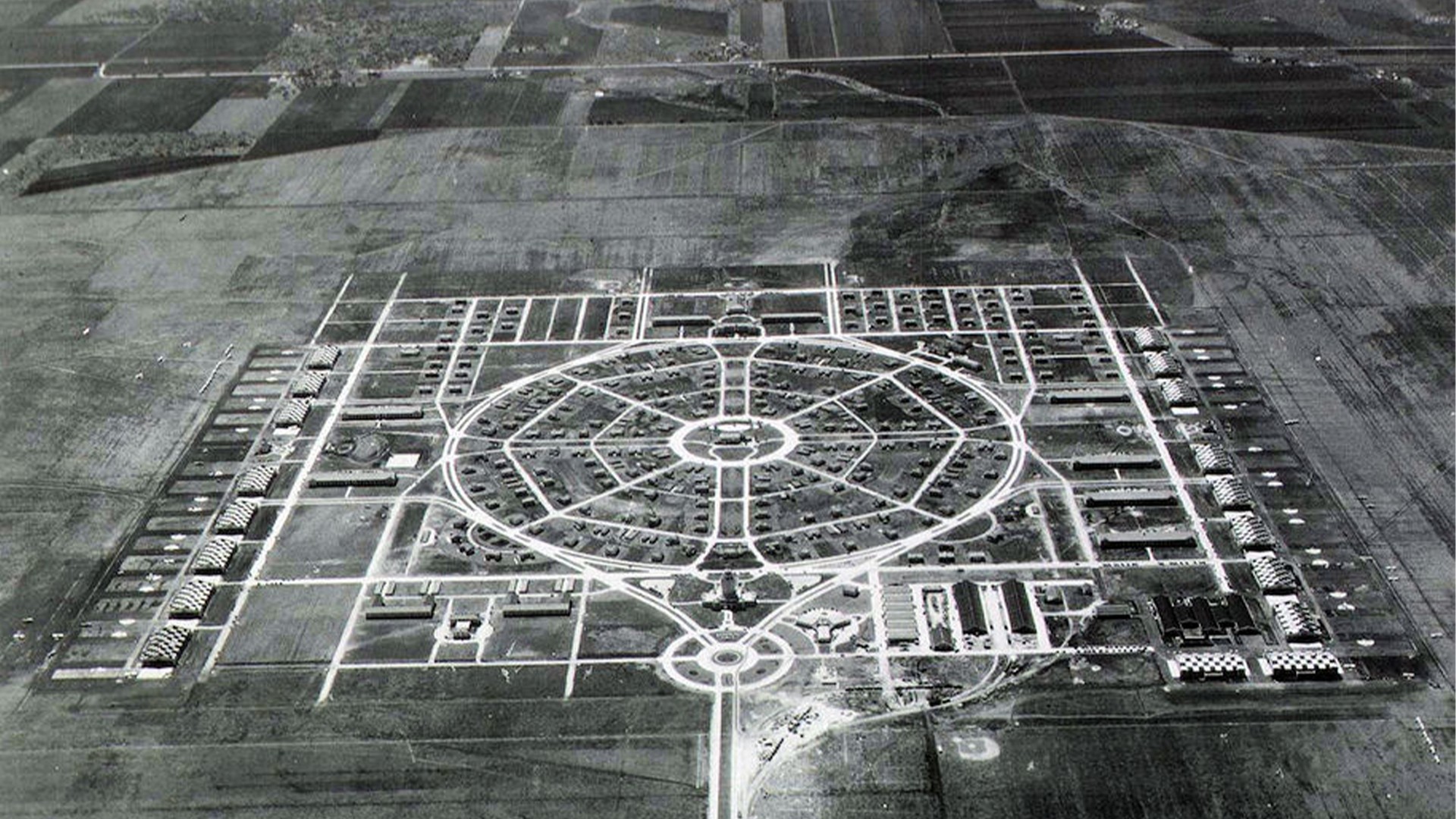

In 1927 Bone returned to active duty with the Army Air Corps Reserves and served as utilities and planning officer at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, where he was also associated with A.G. Ranney in landscape engineering and subdivision work. After proffering his ideas for the landscape design of a new airfield, which embodied the latest airport design theory and practice, Bone was selected for the plum assignment—to assist with the construction of the 2,385-acre U.S. Army Air Corps Training Center at Randolph Field (now Randolph Air Force Base), a project with a price tag of nearly $10 million. From November 1928 to December 1932, he planned, organized, and maintained the project, attracting attention for innovations: establishing a nursery at Randolph to cultivate plants to be used at the site and collecting seedlings and plants to grow in its hothouse during whirlwind flights across the American Southwest.

Inspired by City Beautiful and Garden City concepts, the Randolph Field design specified buildings grouped according to function and situated in separate quadrants of a circular plan. For the landscape plan, Bone conducted studies of the area soils, groundwater supply, and climate to inform his selection of plants—Spanish and live oak trees, Pfitzer juniper, quinine bush, Italian cypress, and a variety of cacti—to complement the Spanish Colonial architectural motif. He sodded the 1,900-acre landing field with Bermuda grass, which was a durable surface for aircraft takeoffs and landings and an attractive green space for much of the year.

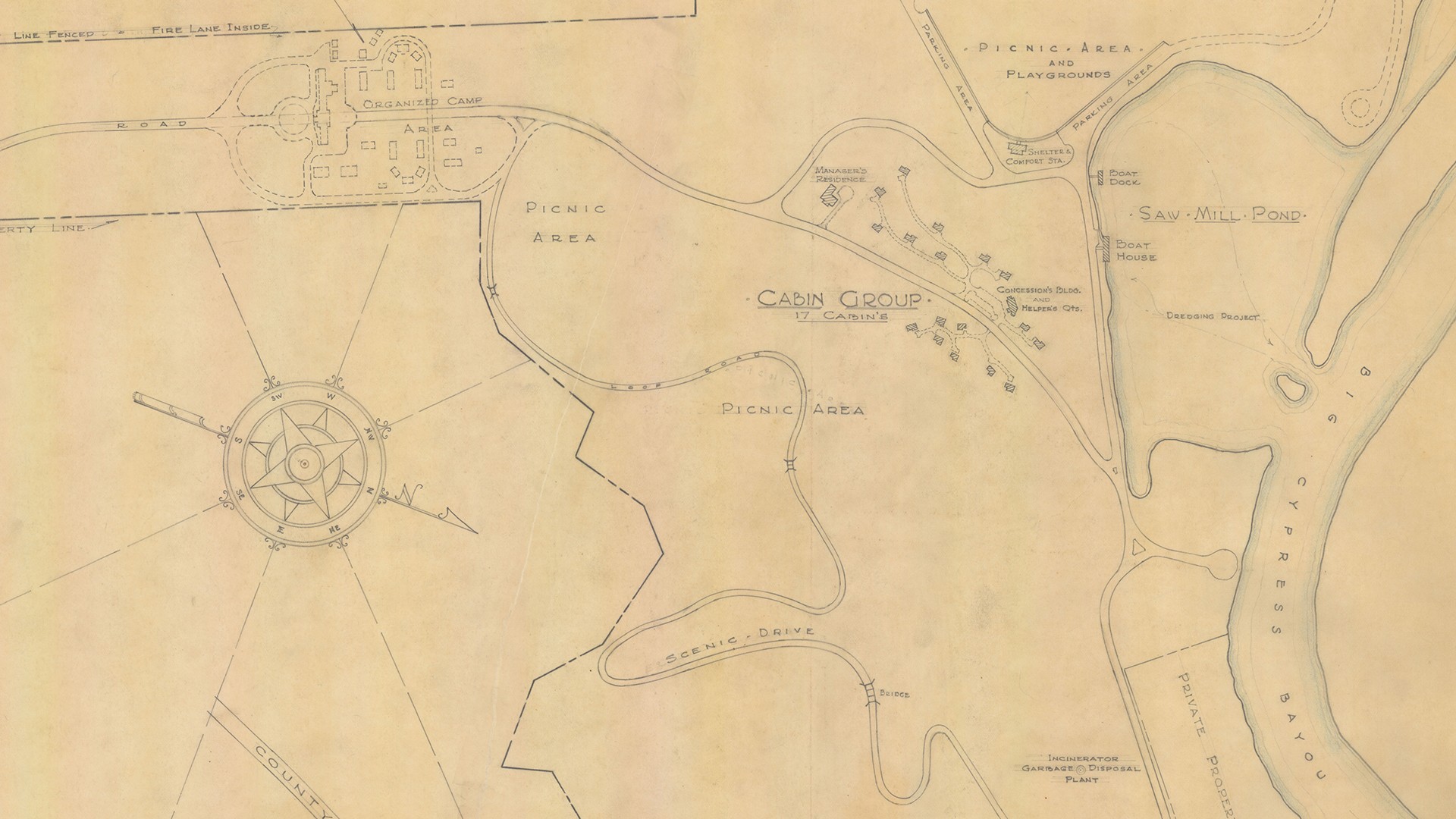

As landscape engineer for Barksdale Field in Shreveport, Louisiana, Bone designed a Beaux-Arts radial plan. He entrusted his assistant, landscape architect Hugh K. Harris, with its major installation. From his home base in San Antonio, Bone flew to Barksdale twice a month to monitor quality and progress.

Bone’s accomplishments were recognized with two promotions, to first lieutenant in 1928 and later to captain. After completing five years of service, Bone remained as consulting landscape architect and advisor to the commanding officer at Randolph while obtaining treatment for rheumatismat Fort Sam Houston hospital during a six-month period in 1933.

Like many landscape architects and planners, Bone found employment with the National Park Service (NPS) in the depths of the Great Depression. Beginning in 1934, he worked on state park development in Texas as a landscape architect. One of his first assignments was at Balmorhea, but poor health dogged him there, and he transferred to Bastrop, where the planning assignment, climate, and proximity to San Antonio hospitals suited him better.

Set within the Hill Country’s “Lost Pines” and built from native timber and local sandstone, Bastrop State Park became the masterpiece of architect Arthur Fehr, landscape architect Norfleet Bone, their foremen, and enrollees in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). (Notably, the buildings were saved from a devastating fire in 2011). By 1935 NPS officials lavished praise on the park for its refectory and cabin area, all beautifully sited, with a loop road and water features. Bone’s landscaping plan, described as “prosecuted vigorously,” was achieved with some 50 species of native shrubs and trees transplanted from nearby areas to achieve ornamental effect. He designed and supervised construction of built features along Copperas Creek—a naturalistic dam, picnic facilities, and footbridges. Bone also oversaw work on two of the park’s overlook structures, which were completed in 1935. By the spring of that year, the refectory building was complete and work was underway on the stone terraces and other sites in the park.

Bastrop’s innovative design and construction earned Bone a trusted role among park leaders; chief engineer C.O. Whitaker relied on him for designs, progress reports, and inspections. During his tenure with the NPS, Bone put his engineering and landscape marks on a number of important parks throughout Texas: entrances, fences, and bridges at Lake Corpus Christi; landscaping plans for Lake Brownwood; a parking and picnic area at Lake Austin. But Bone’s imprint was nowhere stronger than at Bastrop State Park.

When CCC work wound down and the Second World War was underway, Bone left the NPS to join the engineering firm of Bartlett, Norris, Coltharp & Miller during construction of Hondo Army Airfield. Although offered a permanent position as an engineer, he accepted the role of U.S. district engineer for the San Antonio District, at Fort Sam Houston, where he was responsible for planning and supervising the grassing of some twenty airfields in the district. After completing that work, Bone transferred to San Antonio’s Brooks Field as superintendent of field maintenance with the Post Engineers, which allowed him to remain involved in Randolph Field’s further development.

Bone’s diverse work during the war proved to be a hiatus in a long career spent working on Texas state parks. In addition to the years he worked for the NPS (1934-1942), he dedicated himself after 1945 to the Texas State Parks Board, completing projects the war had slowed or stopped. Bone finished some of the designs and plantings at Caddo Lake State Park, Cleburne State Park, and Possum Kingdom State Park, refurbishing and sometimes altering designs that had been installed during the 1930s. Bone was a good manager, traveling inspector, and an indefatigable ambassador for public parks. He developed working relationships with the concessionaires in whose hands the parks were largely placed during the 1940s and 1950s. His task was difficult because many of those entering the new “profession” of park operation during those postwar years lacked any kind of training, and because public funds provided for park maintenance were skimpy at best.

When the State Parks Board merged with the Texas Game and Fish Commission to become the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department in 1963, Bone retired. He was an honored member of the American Society of Landscape Architects, the National Conference on State Parks, and several fraternal organizations. Norfleet Bone died at his Austin home in 1978.

Spanning 50 years, Bone’s career included military service and public park service with relatively short breaks for education and private employment. Only recently have his career and work begun to receive the attention they deserve. In 1997 Bastrop State Park was recognized as an outstanding example of the NPS Rustic design and the Picturesque movement and was designated a National Historic Landmark, one of just seven state parks in the United States so distinguished. In 2001 Randolph Air Force Base in San Antonio was designated a National Historic Landmark. In 2009 Bone was named posthumously as an Outstanding Alumni of the College of Architecture at Texas A & M University for his contributions to Texas.

Bibliography

Brandimarte, Cynthia and Angela Reed. Texas State Parks and the CCC: The Legacy of the Civilian Conservation Corps. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 2013. This well-illustrated book chronicles the history of the CCC-built state parks and includes information on preservation efforts and individual parks.

Carr, Ethan, with Ralph Edward Newlan, James W. Steely, and Susan Begley. “National Historic Landmark Nomination: Bastrop State Park,” National Historic Landmarks Survey, 1997.

Clow, Victoria G., Lila Knight, Duane E. Peters, and Sharlene N. Allday. The Architecture of Randolph Field, 1928-1931. Plano: Geo-Marine, Inc. and U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, Fort Worth Division, 1998. This report includes a chapter on the landscape design at Randolph Field and details about Bone’s contributions.

Steely, James Wright. Parks for Texas: Enduring Landscapes of the New Deal. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1999. The history of the development of state parks in Texas under the direction of the National Park Service and the CCC is the focus of this comprehensive book.

Interview with Dennis Cordes, William N. Bone, and Bobbie Dawn Bone Kemp, 4 June 1997, Austin, Texas.

The Texas State Archives and Library Commission has digitized many of the CCC-related drawings of the state parks. A searchable database makes it possible to locate plans designed or drawn by Bone. For access go to: https://www.tsl.state.tx.us/apps/arc/CCCDrawings

The Special Collections at the University of Texas at San Antonio has a collection of Norfleet Giddings Bone’s papers and is open by appointment. It includes personal and family information as well as documents relating to his military career as a landscape architect and his employment with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. For access to the finding aid go to: http://www.lib.utexas.edu/taro/utsa/00104/utsa-00104.html

About the Authors

Cynthia Brandimarte, Ph.D., directs the Historic Sites and Structures Program for Texas State Parks at Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. She is the author of Texas State Parks and the CCC: The Legacy of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Susan Allen Kline is a historic preservation consultant in Fort Worth, Texas, who writes about history and parks in the Fort Worth area.