Nostalgia 2.0: Has Historic Preservation Become a Spectator Sport?

Nostalgia is suddenly under siege - particularly in the guise of historic preservation. Nostalgia, once roused by the demolition of New York's Penn Station, was a great motivator in saving Grand Central Terminal. Today, however, the form of nostalgia we know as historic preservation is getting beaten up on all sides. (This strikes me as ironic at a time when Woody Allen is finding commercial success with his dreamy and nostalgia-laden Midnight in Paris). National and state level budgets are being shredded, a recent exhibition at the New Museum in New York City demonized it, and recent pieces in the New York Times offered convenient and strange characterizations of its intent, import and impact. Mind you, the modern historic preservation movement isn't a blameless victim and certainly suffers from many self-inflicted wounds. But, this pile on is unprecedented, and more troubling, people seem to be content to sit on the sidelines and watch the slaughter (if they even bother to care).

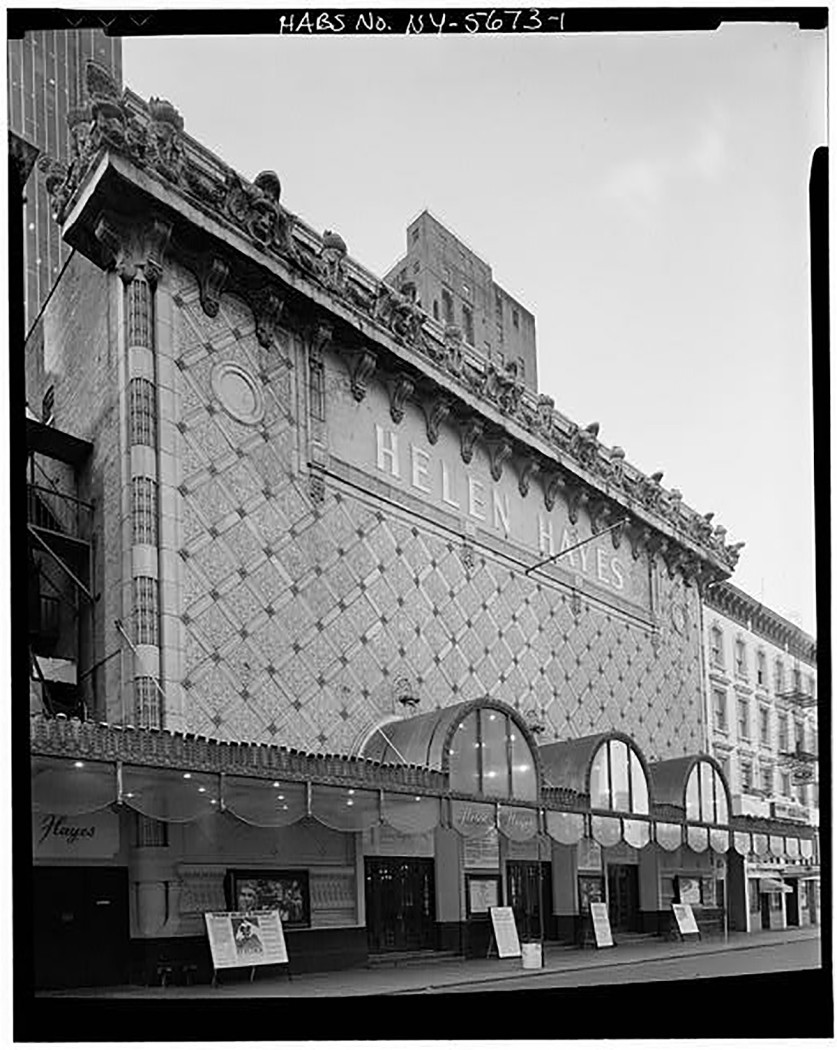

Now for a quick detour/confession to provide some context. Whenever I'm in New York's Theater District I'm reminded of The Great Theatre Massacre of 1982, recalling the demolition that year of the Helen Hayes (originally Fulton), Morosco and Bijou theatres to make way for the Marriott Marquis Hotel.

I was a landscape architecture student at Syracuse back then and journeyed down to New York on People Express Airlines (remember them?) for $29 (really!) and joined a rally Save the Theatres had organized. After singing America the Beautiful, a bunch of us were carted away, though not arrested, in a paddywagon (which I shared with Lauren Bacall, Jason Robards and Christopher Reeve).

Now, nearly three decades later I look at that 45-story hotel and know we're no better off. Does that make me nostalgic? Perhaps. Do I wish those theatres were still here? Absolutely!

So let's examine what's happening. Consider this: the historic preservation movement has helped save such treasures as Acoma Pueblo, President Lincoln's Cottage, Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin, the homes of Edith Wharton, Mark Twain and Harriet Tubman, as well as the Star-Spangled Banner and the World Trade Center Model. Various grass roots groups and organizations were involved, but all of these aforementioned projects have one thing in common, all are recipients of symbolically and strategically important grants from Save America's Treasures (SAT), a public-private partnership between the National Park Service and the National Trust for Historic Preservation launched in 1998 that has leveraged federal dollars to raise millions more to do what its title suggests, save America's treasures. Well, SAT got shafted in the current budget and, after an enviable legacy of successes, will be forced to shut its doors on June 30. Oh, and Preserve America has also been kicked to the ground.

A good example of state-level antipathy can be found in Texas where Governor/ersatz-presidential aspirant Rick plans to eliminate the Texas Historical Commission. According to the non-profit Texas Public Policy Foundation's recommendation: "at a time when we are trying to make difficult decisions about preserving certain services to Texans, funding for programs like courthouse preservation is not the state's top priority." Perhaps the greatest irony in all of this is that these recent cuts are due in part to the Tea Party Movement's success in the last election - the same folks parading around in tricorn hats waxing nostalgically and loudly, about the Founding Fathers and America's roots.

Over at the New York Times, soon to be departing architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff reviewed the Rem Koolhaas-curated New Museum exhibition Cronocaos. In An Architect Fears that Preservation Distorts Ouroussoff writes that Koolhaas, "paints a picture of an army of well-meaning but clueless preservationists who, in their zeal to protect the world's architectural legacies, end up debasing them by creating tasteful scenery for docile consumers while airbrushing out the most difficult chapters of history. The result, he argues, is a new form of historical amnesia, one that, perversely, only further alienates us from the past." Ouroussoff, it seems, concurs.

In her New York Times op-ed rebuttal Death by Nostalgia author Sarah Williams Goldhagen writes, "instead of bashing preservation, we should restrict it to its proper domain. Design review boards, staffed by professionals trained in aesthetics and urban issues and able to influence planning and preservation decisions, should become an integral part of the urban development process."

Goldhagen's backhanded compliment/attempt to contextualize preservation and put it in its place misses the point by only focusing on its professionalization - what about the indescribable feeling that comes from within that can inspire us to take action? The indescribable feeling that caused a landscape architecture student in 1982 to race to New York and join scores of others to try to save some theaters.

Dare I say this, but we can learn much from the mission of Tea Party Patriots, which states: "We recognize and support the strength of grassroots organization powered by activism and civic responsibility at a local level." The New Museum's Cronocaos press release speaks of the growing "empire" of preservation. If historic preservation is an "empire" then maybe it's time for the empire to strike back. The modern historic preservation movement needs to take action: the current climate demands that it recast itself, build better and more strategic bridges with the design community, rebrand and broadcast its message, and in the process get back in touch with its roots.

This Birnbaum Blog originally appeared on the Huffington Post website on June 23, 2011.