The Obama Library Is Going in Jackson Park - What That Means

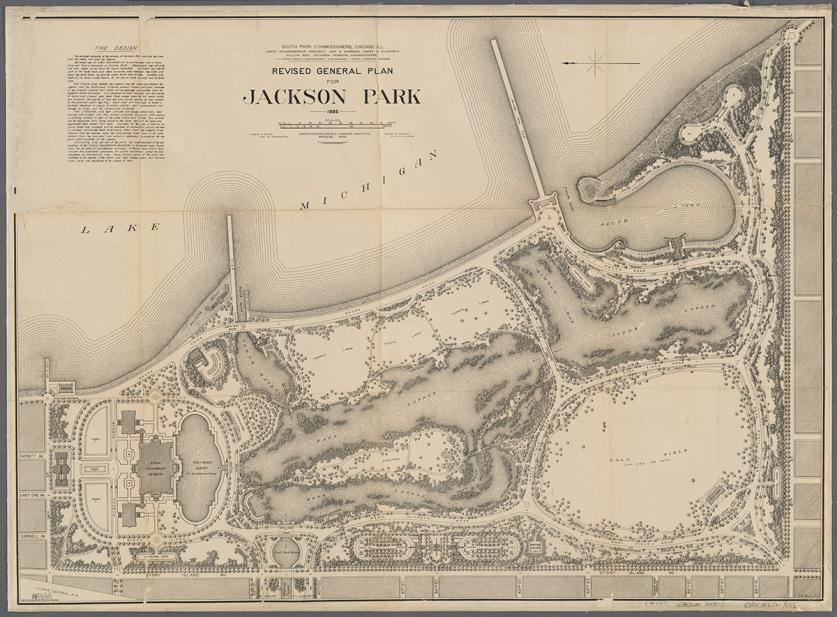

The last major remaining question about the Obama Presidential Library—which Frederick Law Olmsted-Calvert Vaux-designed park would become the building site for the facility—was answered on July 27 when news leaked out that the First Couple had decided on Jackson over Washington Park.

This is a good-news/bad-news result.

Washington Park, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, is considered to be (along with Central and Prospect Parks in NYC, and Franklin Park in Boston) one of the four premiere, largely intact Olmsted-designed Country Parks in the nation, according to renowned Olmsted scholar Dr. Charles Beveridge. Had the Obama Library gone here, it would have claimed some 23 acres along the park’s western edge, which would have been both devastating and irreparable.

Jackson Park, by contrast, has already been compromised. As Ed Keegan wrote in Crain’s Chicago Business: “Jackson Park is the better choice, in that the less significant piece of landscape architecture will be redesigned, but it’s unfortunate that Chicago’s parks are still considered mostly as open land, ripe for cultural development. In a city where fully landscaped parks remain woefully inadequate for the overall population, it would have been better to locate the new structures adjacent to or near these historic parks, rather than in them.”

Keegan is right, but let me add more. The people of Chicago, and the officials who represent them, were presented with a false choice: surrender land in one of the two historic parks, or lose the library. And with the presidential imprimatur behind this confiscation, the stakes are now higher. It’s a scenario that plays out all too often across the country. But it need not be the case.

We should use the fate of Jackson Park as an opportunity to rethink the value we place on open space and public parkland held in trust for future generations.

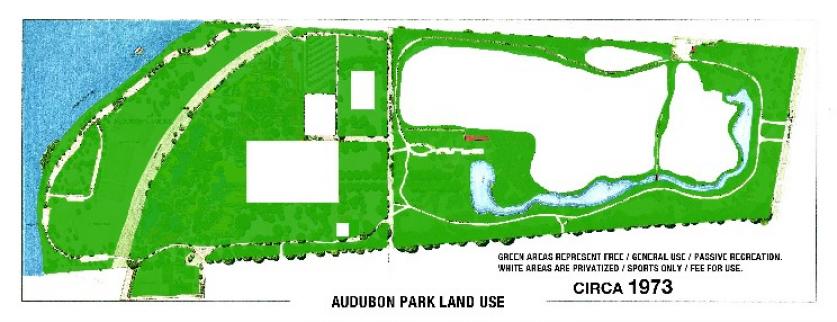

Has the time come to refine how we measure the value of historic parks like Jackson and Washington Parks in Chicago, not to mention Audubon and City Parks in New Orleans, Roeding Park in Fresno, California, and Rahway River Park in Clark, New Jersey? What about the irreplaceable historic and cultural values that are embedded in these places?

The Trust for Public Land’s annual ParkScore® Index ranks land owned by regional, state, and federal agencies within the 100 most populous U.S. cities—including school playgrounds formally open to the public and greenways that function as parks. The ranking criteria include acreage (park acreage as a percentage of city area), facilities and investment (spending per resident), and access (the number of residents within a ten-minute walk). However, the measure of acreage doesn’t take into account parkland and open space lost to new construction within a park. Consequently, the measure of overall acreage may not be affected by new construction within a park, but the amount of actual open space is.

In New Orleans, for example, open space in Audubon Park today only accounts for about one third of the park; it’s a sliver around the park’s periphery, along with some other limited interstitial space. City Park could soon lose eight acres to the Children’s Museum expansion. That’s a quantitative and qualitative difference that needs to be measured, particularly as it affects many residents’ quality of life.

With the renaissance of cities, and more and more users taking advantage of our municipal parks, when will the public demand that open space be left open? Will we draw a line in the grass that says municipalities can no longer repurpose meadows for museums and trade pastoral parkland for parking? Will we declare that parks held in public trust—especially masterworks designed by great landscape architects—are not free for the taking?

The majority of our park users—more than 70%—use public parks for passive enjoyment. These vulnerable spaces are living, connective tissue composed of soil, rock, trees and lawn; but more than that, they tell our stories as a community and a nation. It’s ironic, therefore, that this week’s auction of ashtrays, silverware, and furnishings from the famed Four Seasons restaurant in New York spurred journalistic lamentations among some of the nation’s design critics, while the confiscation of parkland held in trust for 150 years in Chicago produced nary a sigh.

This article first appeared in the Huffington Post on July 28, 2016.

Postscript: To learn more about Chicago's great parks, access the What's Out There Chicago Guide, which is optimized for iPhones and similar handheld devices.