Olmsted’s Staten Island Farm

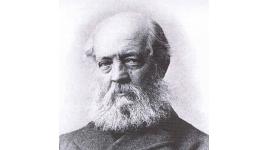

Frederick Law Olmsted achieved an outsized impact on the world as a journalist, head of a Civil War medical relief organization, and as the designer of a series of landscape masterpieces such as Central Park, the Stanford University campus, and Boston’s Emerald Necklace. For six years–a critical, formative period–the man who would eventually become known as the ‘father of American landscape architecture’ worked a farm on Staten Island.

In 1848 Olmsted’s ever-indulgent father, who had bankrolled so many of his son’s youthful endeavors, purchased the farm for $13,000. It consisted of 130 acres on the island’s south shore, gently sloping down to Raritan Bay. In the distance, the Navesink Hills of New Jersey were visible, a spot where Henry Hudson once anchored his ship, the Half Moon. Olmsted described the view as “wondrous beautiful.” He named his property Tosomock Farm, a tribute and twist to the name of its first owner, Petrus Tesschenmakr.

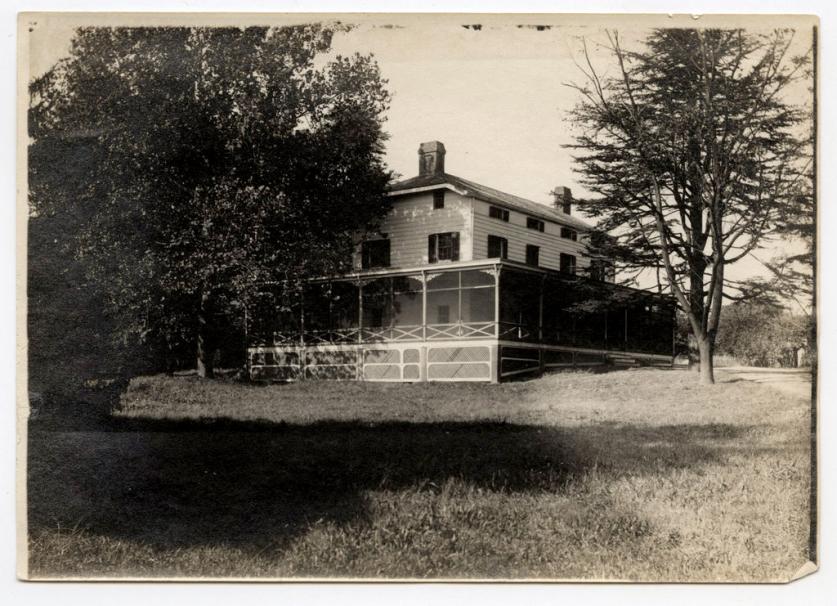

The property had a rich history, dating to 1685. That is when Tesschenmakr, a Dutch Reformed Church minister, built a one-room stone structure. (Tesschenmakr soon decamped to Schenectady, where he and his flock perished in a tomahawk attack by Native Americans.) The house then went through a series of owners, who made various additions. Supposedly, George Washington stayed at the house while assessing Staten Island’s fortifications during the Revolutionary War. (Then again, almost any notable house from this era has a Washington-visited-here legend.) By the time Olmsted became owner, the house had expanded to two stories, nine bedrooms, an ample kitchen, and a porch wrapping around three of its sides. There was plenty of room for Olmsted’s spinster Aunt Maria, as well as Nep and Minna, his dog and cat.

Olmsted, who had already worked as a surveyor, clerk, sailor, and failed Connecticut farmer, threw himself into this new venture with aplomb. He transformed the farm agriculturally. The previous owner, a retired doctor and hobby farmer, had been unimaginative, planting wheat almost exclusively. Indulgent father notwithstanding, Olmsted recognized that he needed to make this latest endeavor a success. Thus he focused on growing fruit and vegetables. It was an eminently sensible strategy, given that he was right on the doorstep of New York City, a vast and ready market for his crops. Olmsted grew corn, cabbage, and lima beans; peaches, plums, and raspberries. His produce earned him many prizes at Richmond County agricultural fairs, including a silver spoon for his pears.

On his ample acreage, Olmsted also started a nursery business, a stab at further diversification. Not only would he be selling fruit, but he could also sell fruit trees to his fellow farmers.

The timing of Olmsted’s move to Staten Island proved fortuitous. In short order, two of the most important people in his life moved to nearby Manhattan. John Olmsted, his younger brother, enrolled in medical school; Charles Brace, a close friend, began studying at Union Theological Seminary, planning to enter the ministry. The two were frequent visitors. Olmsted furnished his guests with slippers and put out baskets piled high with the fruits of his labors, quite literally. Ever the enthusiast, Olmsted regaled his visitors with an assortment of plans and schemes. Brace described a weekend spent with Olmsted at Tosomock Farm: “But the amount of talking upon that visit! One steady stream … interrupted only by meals and some insane walks on the beach.”

As Olmsted settled into farm life, he expanded his focus beyond the strictly utilitarian. To bolster an already spectacular view, he moved an entire barn to a new location, hiding it behind a knoll. As for a puddle near the house, used to wash off wagons, he shored its edges with stones. Presto!–an ornamental pond. No formal training guided Olmsted’s choices. He was simply doing what came naturally, drawing on an appreciation for landscape rooted in his Connecticut upbringing. But these modest improvements are rightly seen as Olmsted’s first foray into landscape architecture, the very profession that he would pioneer in the United States.

Olmsted also rerouted a carriage driveway to better conform to his land’s topography, so that it approached the farmhouse in a gentle sweep. To further beautify his farmstead he planted a variety of trees: black walnut, elms, gingko, Osage orange, and a pair of Cedars of Lebanon.

On Staten Island, Olmsted’s horizons began to expand. By the 1840s its population had swelled to 15,000, many of them prosperous New Yorkers drawn to its rural charms as a place to summer or retire. He’d left Hartford behind and was now in the ambit of sophisticated Manhattan.

When King Louis Philippe abdicated the French throne, Olmsted was so excited to share the news that he dashed to a neighboring farm. There he made the acquaintance of Cyrus Perkins, a retired doctor from New York City. More significantly, Olmsted met Mary, his 18-year-old granddaughter. Olmsted was immediately struck by her sharp wit. He described Mary as “just the thing for a rainy day–not to fall in love with, but to talk with.”

Upon meeting Mary, Brother John had a very different impression. She struck him as decidedly someone “to fall in love with.” The two were soon married.

Sadly, John was destined to die of tuberculosis. His last words to his brother, contained in a deathbed letter, were: “Don’t let Mary suffer while you’re alive.”

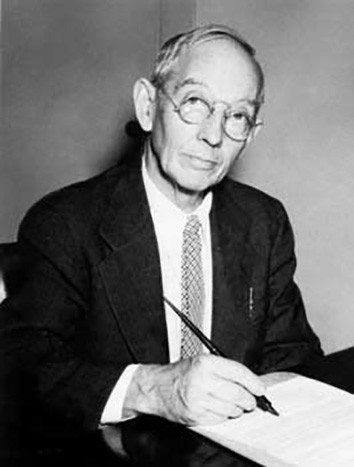

In a rather Biblical turn, Olmsted married his brother’s widow and adopted her three children. Their union would also produce four more children, two of whom would die in infancy, but one of whom (Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.) would follow in his father’s footsteps. Where Olmsted was landscape architecture’s nineteenth-century pioneer, FLO, Jr., would become a preeminent twentieth-century practitioner. He would retire in 1957 having seeded the United States with his own collection of masterful green-space creations. But it should be remembered that FLO, Jr.’s, roots stretch back a century to Staten Island and that first meeting between Mary and his father.

Another Staten Island connection was William Henry Vanderbilt, the fantastically wealthy, eldest son of the Commodore himself. After seeing the improvements Olmsted had made to his property, Vanderbilt hired him to lend similar touches to his farm in the nearby New Dorp neighborhood. This can rightly be considered Olmsted’s very first landscape-architecture commission. Thus was born a 50-year association, which saw Olmsted work on the sprawling properties of assorted Vanderbilts, culminating in his design for the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina.

While Tosomock Farm furnished Olmsted with new connections and expanded horizons, he felt increasingly drawn to the wider world.

In 1850 Olmsted set out on a walking tour through England, the seat of scientific farming. Upon return, his mind swirled with ideas for agricultural innovation. For example, he urged Staten Island farmers–in emulation of a practice he had observed during his tour–to lay clay pipes beneath their fields to carry off excess water.

In 1851 Olmsted made a pilgrimage to Newburgh, New York, to see Andrew Jackson Downing, the eminent gardener and rural tastemaker. During the visit, Olmsted also met one of Downing’s employees, a young English-trained architect named Calvert Vaux. This first meeting was unremarkable; both men would recall only the faintest details in the years to come. But already, Olmsted’s amblings were suggesting pursuits beyond farming. To wit: one of the notable stops on his earlier English walking tour had been Liverpool’s Birkenhead Park, acknowledged as the world’s first publicly funded park. Olmsted simply tucked this away in his feverish brain for future reference.

Olmsted was growing restless. Late in the autumn of 1852, he departed Staten Island for yet another sojourn. As always, hired hands would oversee Tosomock Farm during his absence. On this occasion, he had been hired by the New York Times (then a start-up newspaper) to travel through the American South, reporting on slavery. That may seem an unlikely employment opportunity, but slavery represented a form of agrarian economy, albeit a brutal one. Who better to report on it than Olmsted, a literate farmer? During two separate trips, he wrote a series of dispatches that captured the antebellum South in all its thorny complexity. His work helped build the reputation of the upstart Times. Historian Arthur Schlesinger has described Olmsted’s southern reportage as “the nearest thing posterity has to an exact transcription of a civilization which time has tinted with hues of romantic legend.”

Predictably, farming could not hold Olmsted. The pursuit had at least occupied him longer than earlier professions, such as surveying and sailing. In 1855 he moved to Manhattan, planning to become a writer, intent on entering what he termed the “literary republic.” Never again would Olmsted live on Tosomock Farm, although ownership would remain in his family for four more years. By then, Olmsted had switched professions yet again after winning a competition (along with new partner Vaux) to transform a homely, rectangular, 778-acre plot of land, smack in the middle of Manhattan, into Central Park. This would set Olmsted on course toward the greatest achievements of his varied and busy life: a series of timeless landscape-architectural creations.

Meanwhile, Olmsted’s former farm went through a fresh round of owners. For two decades following the Civil War, Dr. William Anderson devoted the land to growing vegetables that suited the specialized diets of his patients. By the late 1800s, the farmhouse had been converted into the Woods of Arden Inn. According to an old account, it was possible to get “as good a dinner there, as at Delmonico’s.” Even so, the inn went bankrupt and the property was carved up to satisfy creditors. More change came in the 1920s, as Hylan Boulevard was constructed, creating further divisions. By the time eminent naturalist Carlton Beil purchased the property in the 1956, it was greatly reduced from Olmsted’s 130 acres.

The house has sat empty for some years now. In 2006 the New York City Parks Department purchased the 1.7-acre property, which had fallen into disrepair. Olmsted’s pair of Cedars of Lebanon still survives, witnesses to a now-distant era, but the house he inhabited is in dire need of repairs and maintenance.

Fortunately, efforts are underway to restore the property. On October 22, 2018, the New York Landmarks Conservancy (NYLC) launched a successful Kickstarter campaign—garnering $22,000—to fund urgently needed repairs to the house. The campaign was part of the NYLC’s wider fundraising efforts (with an overall goal of $150,000) to stabilize the landmark building. Moreover, the Friends of Olmsted-Beil House was formed in 2018, with the goal of reopening the house by 2022 (the bicentennial of Olmsted’s birth) in order to share its rich and eventful past with the public.

Justin Martin is author of Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted. He serves on the board of Friends of Olmsted-Beil House. To learn more about this preservation effort, please visit https://www.facebook.com/olmstedbeilhouse/