Olmsted on Long Island

Long a source of sustenance from land and sea to feed Manhattan and beyond, Long Island, with its varied scenery of shorelines, woodlands and rolling pastures, its beneficial climate and diverse recreational opportunities, was ‘discovered’ in the late 19th century, beckoning the wealthy elite to establish grand estates, particularly along the north shore. Transportation improvements (development of the Long Island Railroad, completion of the Queensborough Bridge and train tunnels traversing the East River, plus Vanderbilt’s private toll road, the paved Long Island Motor Parkway) spurred interest among the “great wealthy ones,” as local nurseryman Isaac Hicks termed the newcomers, to acquire vast areas of former farmland and small hamlets for private domains of competing grandeur and scale. In so doing, the Island’s former agrarian economy, its population, and its landscape were forever transformed-- with resultant gains and losses. To accomplish this transformation in the period between the late 1880s and the 1930s, the new property owners required architectural advisors of all calibers, skilled craftsmen and artisans, experienced managers, and armies of laborers to sculpt landform, delineating forest and field in order to sympathetically accommodate grand edifices and their ancillary buildings, surrounded by suitably structured and beautified grounds with scenic advantages.

The Olmsted firm was in the vanguard of landscape planning for these new Country Place era estates on Long Island. Beginning in the 1880s with plans by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., for two south-shore properties (the Cutting estate in Westbrook and the summer colony of the Montauk Association), the work continued under the successor firm, Olmsted Brothers, and their partners for decades. Their estate client list, which reads like a Who’s Who of America’s leaders, includes more than 160 entries for Long Island: some mere queries, others resulting in plans, sometimes numbering in the hundreds for complex properties. Whether for modest plots or vast acreage, the Olmsted designers settled buildings of all sizes into the land in harmony with natural features and viewsheds. At Nethermuir (now Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory), Fredrick Law Olmsted, Jr., of Olmsted Brothers, regraded the landscape, enhancing views and creating distinct outdoor spaces. Throughout Long Island Olmsted Brothers advised on property acquisition; architectural character and proportion; well-constructed graceful routes of access within and outside the boundaries; and planting plans, from simple tree and shrub groupings to multiple diversified garden rooms adorned with elaborate features. The firm’s artful plantings are evident at myriad properties, including Oheka Castle, the former Otto H. Kahn estate, where specimen trees and shrubs punctuate terraces and enliven the lengthy entrance drive. At Rosemary Farm (now Seminary of the Immaculate Conception) the firm designed a sizable turf amphitheater overlooking the Sound, accommodating nearly 3,000 people. Across Long Island, the firm emphasized design for a functional purpose, protective of core landscape values and natural assets, rather than simply decorative display.

Of the numerous estates that the Olmsted firm created, few survive that are still held as private family compounds. Most large estates were subdivided or became country clubs or nature preserves and arboreta (i.e. Caumsett Historic State Park Preserve). Some were donated to religious or educational institutions, which could not adequately sustain the architectural or horticultural refinements. Among the few exceptions, the Coe estate, Planting Fields, stands out. After several transitions, it retains its design integrity and is now being stewarded for the public by a public-private partnership that recognizes its significance. The firm was involved in planning for at least fifteen major subdivisions or resort communities throughout Long Island, beginning in 1898. Amid the windswept wildness of Montauk’s eastern tip, John Charles Olmsted laid out roads and lots for residential groupings in Wompenanit and Hither Hills, some of which later became state parkland. Sadly, following subsequent development, little of his planning is still extant. Further west on the scenic Shinnecock Hills, he also planned a similar development, stretching from Peconic Bay to the Atlantic, with easy access from a new railroad station. The roads and lot arrangements here still reflect this early work. Whether on acreage of a former estate (the Cravaths in Locust Valley, the Pratts in Glen Cove, the Whitneys in Westbury, or the Munsey property in Manhasset), or carved from agricultural land (Old Field in Stony Brook or the former Hicks Nursery in Westbury) or from a gravel pit in Northport, Olmsted Brothers shaped graceful residential plots along curving tree-lined streets in communities that today have little recognition that their neighborhood was the result of considered design by the Olmsted firm.

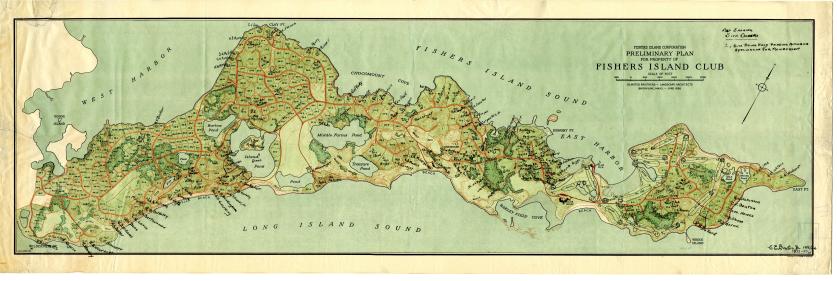

The largest such development undertaken by the firm was for the 2,600 acres of the Fishers Island Club. Beginning in the 1920s, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., working again with developer Frederick Ruth (they had previously designed the Mountain Lake community in Lake Wales, Florida) and colleague Henry Hubbard, transformed this picturesque island in Long Island Sound into an exclusive resort, a project that generated over 1,100 plans and design recommendations for more than 40 private properties. While protecting this unique landscape of rugged grasslands, wooded hollows, and jagged rock-strewn shorelands, they inserted necessary infrastructure to support homes, a clubhouse, a Seth Raynor golf course, and other amenities.

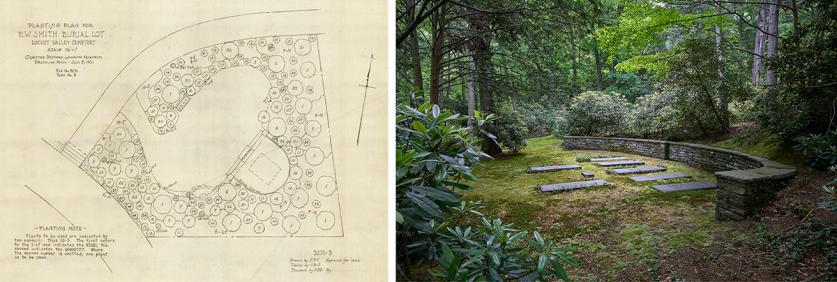

The final concentrated area for Olmsted Brothers’ endeavors on Long Island was not one of their usual emphases—that of cemetery and private plot design. They advised on or planned over 40 such projects. If Long Island’s scenic attractions represented leisure retreats from business life and a more domestic pace, they also promised ‘pockets’ of serenity amid tree-shaded lawns encircled by lush plantings. At the request of their estate clients, the Olmsted firm applied their design and horticultural skills to shaping their clients’ final resting places amid the hills and vales in Cold Spring Harbor and Locust Valley. Initiated by a 1912 request from the De Forest family to expand the Memorial Cemetery of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Laurel Hollow, followed by a 1917 request by a consortium, many with Olmsted landscapes, to develop a new cemetery in Locust Valley, and finally for the Pratt family in mid 1930s to augment their private burial grounds in Lattingtown, the Olmsted partners laid out shrub-enclosed ‘rooms’ and crafted discreet markers for family burials. They additionally shaped graceful roads and paths to connect and meld these unique spaces with more conventional lotting.

Looking forward, there is one area of Olmsted involvement on Long Island still to be explored by scholars – to better understand the role played by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., in the general planning for the Island’s overall development. As a major advisor for the 1929 New York Regional Plan, a pioneering effort coalescing the major innovator thinkers of its day to chart a strategic growth pattern for this expanding metropolitan corridor, Olmsted, Jr., was assigned Nassau and Suffolk Counties. This overall effort evolved into the still-influential non-profit Regional Plan Association to accommodate growth while protecting natural resources in the Tri-State Region. Olmsted, Jr.’s, concerns were several: transportation corridors to connect the urban core with expanding suburban enclaves and with regional recreational assets; laying out potential residential areas balanced with commercial needs; and developing the administrative and legal mechanisms to support long-range planning and to protect resources.

Today, less than one-third of the more than 1,200 Gold Coast mansions built on Long Island’s North Shore between the late 1880s and the 1930s survive. Fortunately, the work of all three Olmsteds, as well as many other Olmsted firm partners and collaborators, can be experienced today. Thanks in large measure to acts of visionary testamentary planning by their original owners, as well as by local and state agencies who received these properties, and even one passionate developer, the public can still experience what it might have been like on Long Island’s North Shore during the Gilded Age.

Examples of the Olmsted firm’s work on Long Island, along with biographies for more than a dozen firm employees who worked in that region, can be explored in What’s Out There Olmsted, a comprehensive digital guide to more than 300 North American landscapes designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., and his successor firms.

Related Content

- Image