Phebe Westcott Humphreys Biography

Phebe Westcott Humphreys (1864-1939) was an author, horticulturist, photographer, garden tastemaker, and early proponent of botanical expeditions by car—she called herself “the chauffeur naturalist.”

She was born in southwest New Jersey near Greenwich, the third of three children of Enos Westcott (c. 1835-1865), a farmer, metalsmith and shopkeeper, and Lydia Martha Mason (1837-1931). Lydia remarried in 1869 to Ephraim Bacon, a farmer who owned about 120 acres. Humphreys credited her fascination with landscapes partly to “an early developed love for outdoor life.” By age 12, she had won awards for artisanship; local fairs gave prizes for her quilt assembled from 17,352 pieces of fabric. She studied at the South Jersey Institute (a private high school) and the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College of Art & Design).

In the late 1880s, she married S. Walter Humphreys (1864-1932), a manufacturer specializing in jams, jellies and condiments. They raised their son Westcott at a mid-nineteenth-century home in Philadelphia’s Germantown section. In 1891, she began writing prolifically about garden and landscape design for periodicals such as House Beautiful, House and Garden, and Harper’s Bazar as well as newspapers and floriculture and farming magazines. About 400 features and monthly columns bear her byline, and many also feature her photos.

Some early writings focus on her experiments at home, trellising vines on umbrella frames, grafting cacti, and making pesticides out of tobacco stems. She published step-by-step advice on building greenhouses, propagating seeds and cuttings, and forcing winter blooms. Humphreys stocked the Germantown grounds and the house’s second-floor conservatory with tulips and other bulbs by the hundreds, plus lilies, roses, geraniums, alyssum, vines such as honeysuckles, and hardy flowering shrubs. Her property in bloom was “the envy of her neighbors,” one newspaper reported.

For her growing readership, she evaluated which “novelties” hyped by florists were “creating a sensation” or revealing themselves as a “flat failure.” After viewing the “magnificent profusion” of blossoms at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, she described how the displays were inspiring homeowners’ cravings for rhododendrons and chrysanthemums. No chore seems to have daunted her; her articles recommend sawing barrels in half to create outdoor waterlily ponds that could be hauled indoors during cold snaps. Her regular columns included “Flora Culture” for Arthur’s Home Magazine and “Suggestions from Last Year’s Diary” and “The Very Latest Floral News Notes” for Success with Flowers. She used charmingly accessible language to encourage readers to take chances with planting concepts. Wisteria was prone to “over-affectionate hugging” of trees and building parts, she warned, and she described long-tongued Arethusa orchids as “mocking disdainfully” any nearby common flowers.

By the late 1890s, Humphreys’ scope had broadened. She reported discoveries from overseas: how Japanese chefs were making use of burdock (which Americans considered a “pesky weed”), and how African insects drilled piercings in trees that whistled in the wind. She described new horticultural inventions, such as riding lawnmowers with combustion engines and flowerpots with wired-together separable halves (for easy transplanting). She cautioned that plants harvested for commercial purposes, such as rubber trees and Spanish moss (useful as packing material and upholstery stuffing), were being “exhausted by gross carelessness” while invasive European hawkweed was gaining footholds. She praised women pursuing careers in horticulture and landscape design, including a “wide-awake” recent grad named Beatrix Jones (later Farrand). Another recurring theme in Humphreys’ writings is plants’ potential to transform lives. She reported on charities giving away cut flowers and houseplants and offering horticulture classes, so that children living in tenements could benefit from nature’s “silent, sweet, persuasive influences.” (Humphreys, while contributing dozens of articles to magazines annually, also found time to write four children’s books, two of them about animal habitats.)

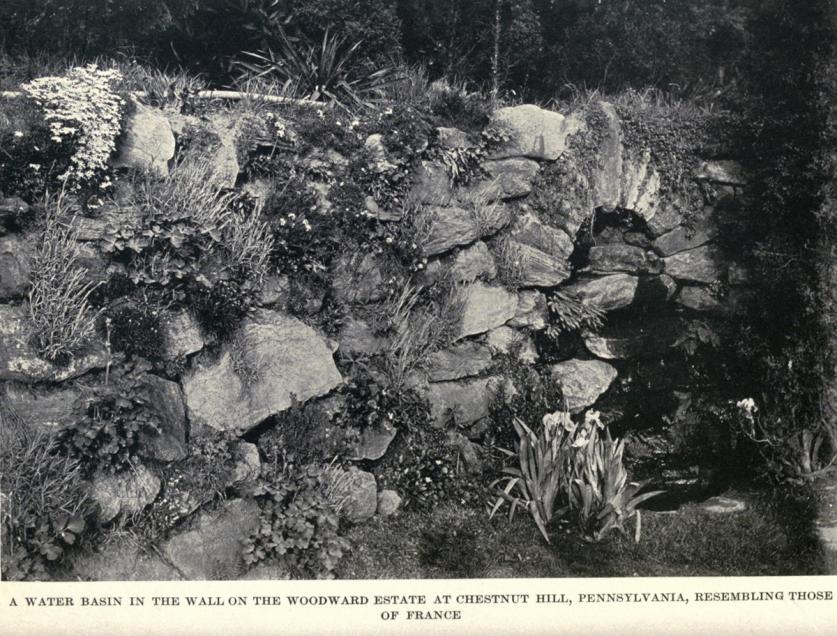

In the early 1900s, Humphreys further expanded her repertoire with site visits, traveling with her husband and son in a Rambler roofless car. Her pioneering guidebook for car travelers, The Automobile Tourist (Philadelphia: Ferris & Leach, 1905), suggests daytrips to scenic spots around Philadelphia including southern New Jersey’s “berry patches and vineyards” tended by Russian Jewish immigrants. On the road, she collected ferns and wildflowers to transplant to Germantown and gathered flowering branches, “standing erect from the machine.” She photographed and wrote about bark-walled mountainside hermitages as the family headed into the Poconos. She took notes and snapshots from a houseboat’s decks, while exploring Pennsylvania’s canal system. (At each lock, the passengers braced themselves for the river’s “surge and tumble and swell” under the supervision of “the lonely lock-keeper and his wife.”) Humphreys interviewed Florida grapefruit growers and Philadelphia Main Line millionaires installing Italian balustraded terraces and Japanese footbridges. On trips overseas, she analyzed Bermudan streets lined in cedars and wildflowers sprouting from crevices in fortresses at Cherbourg, France. She grew increasingly opinionated about ways to create harmonious landscape designs, free of “inappropriate and inexcusable” stylistic mixtures, even on “the smallest nook of ground.”

Greenery and fishponds can be perched on rooftops “even in the most unexpected places in the poorer districts,” she wrote in a 1903 report on “roof-garden mania” for The Designer and the Woman’s Magazine. That year she critiqued tastes in gateways for The Cosmopolitan: comically aspirational patrons were asking architects for snobbish heraldic symbols on their crenellated entryways, in emulation of “the turrets and donjon-keeps of popular actresses.” She meanwhile grew concerned for landmark estates around Philadelphia, as subdivisions threatened trees that had survived Revolutionary War battles. She profiled about 50 properties built as early as the seventeenth century in a five-year, monthly series for Table Talk magazine, titled “Famous Banqueting Houses.” (A number of the sites, including Grumblethorpe in Germantown and Mill Grove in Audubon, have survived as museums.)

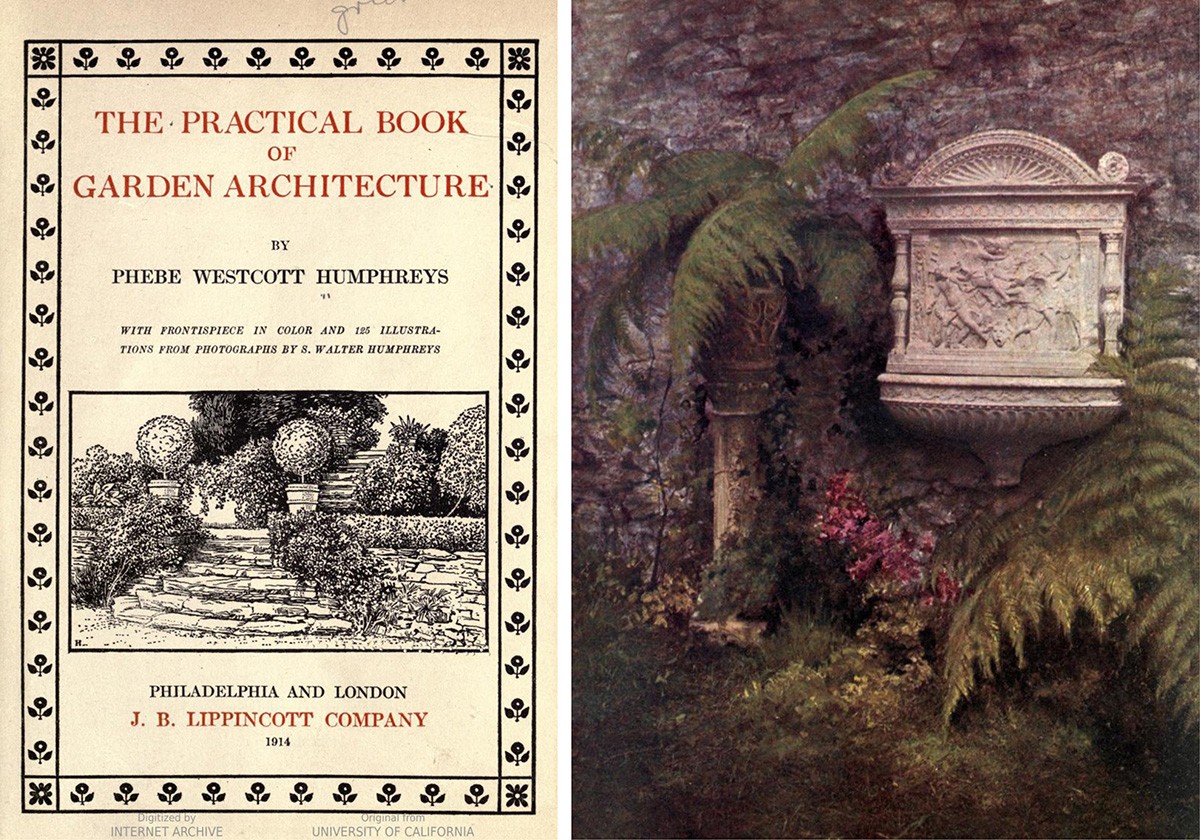

For her crowning achievement, The Practical Book of Garden Architecture (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1914), she summarized her decades of landscape observations in the U.S. and overseas. She interviewed authorities including the sculptor Waldo Story, and she quoted her own past articles about covering bridge railings with flowering vines, keeping predators away from birdhouses, and converting springhouses into artists’ studios. She laid out technical details of choosing power sources for water pumps and exterior lanterns, killing lake algae with copper sulphate, and insuring good drainage for swimming pools and tennis courts. Every chapter—their wonderful headings include “the use and abuse of adapting the Italian pergola” and “revival of the wall fountain”—offers suggestions for maximizing “restfulness and repose” and avoiding “overdoing and incongruity.”

The volume received rave reviews. The botanist Charles Howard Shinn praised its “stately air” and a wealth of suggestions that “sometimes even betters nature herself.” Publishers’ Weekly mused that realizing her ideas would lead to “a garden so full of surprises that you half expect to find in some big tree a door leading into fairyland.” In 1915, as war engulfed Europe, The Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society lamented that England’s “educated, artistic women gardeners” would have little chance to experiment with Humphreys’ proposals for glass espalier walls and railway-tie retaining walls, until “peace returns with prosperous, restful days.” And the book has remained on the desks of influencers. Linda Joan Smith, in Smith & Hawken Garden Structures (New York: Workman Publishing, 2000), quotes Humphreys at length about the art of “giving thoughtful consideration to our gateways.”

The Practical Book was Humphreys’ last substantial published work. A handful of brief how-to articles later bore her byline, in periodicals including Country Gentleman and Farm and Fireside. At the time of her death (due to injuries suffered when she was struck by a trolley), she was still living at the Germantown house where the bouquets indoors and out had been “the envy of her neighbors.”

Bibliography

Hundreds of Humphreys’ photographs of buildings and landscapes survive at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. The Germantown Historical Society owns a handful of her photos, many depicting eighteenth-century churches and homes.

Most of her books and magazine articles have been digitized and made publicly available through Google Books, archive.org, and hathitrust.org. Her Wikipedia article, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phebe_Westcott_Humphreys, contains links to many of those works.