Preserving the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Asbury Park

Traditional approaches to the stewardship of cultural resources in America are used to dealing with things that are tangible, such as landscapes, buildings, artworks, and the like. But not everything worth keeping is something that can be touched—including the cultural heritage of sound. The Asbury Park African-American Music Project (AP-AMP) is determined to ensure that the music and performances that put their community on the map will not be lost forever.

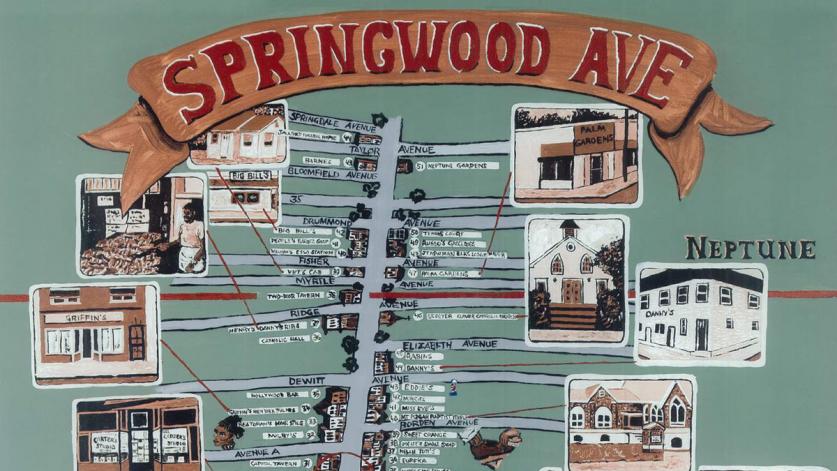

Early in 2017 in part through two days of workshops at Creative Asbury Park, a few Asbury Park community members realized that the standard methods of historic preservation were poorly adapted to telling the story of the music, culture, and history of the city’s Springwood Avenue, the well-known street that has long been the heart of the city’s African American community despite the loss of its buildings over time. Through the library, the community submitted a proposal to the New Jersey Historical Commission, seeking support for the Asbury Park African American Music Heritage Project. In the summer of 2017, the library received a grant from the commission to gather information, conduct oral history interviews, and create awareness of the initiative. Although this heritage has been celebrated through various exhibits, programs and publications over the years, it is not history that has been readily accessible or shared as central to the history of Asbury Park.

Founded in 1871 as a seaside resort community by New York broom manufacturer James A. Bradley, Asbury Park is located along the coast some 50 miles south of New York City. Bradley envisioned the town as a place of progress and innovation and a haven for forward-thinking residents, even as his own thinking about the town included segregationist policies meant to keep African Americans and other minorities behind the scenes as subservient fixtures in a leisure economy. With its wide, tree-lined streets, parks, a central business district, and scenic oceanfront complete with a boardwalk, the town nonetheless became a vacationer’s paradise from the 1880s to the 1960s, drawing crowds of more than 600,000 visitors annually. The local African American community west of the boardwalk saw the surge of tourism and money as an opportunity, and opened live-music clubs along Springwood Avenue, which attracted such artists as Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, and Billie Holiday, as well as local music legends such as Dee Holland, Cliff Johnson, and Al Griffin. The establishments were part of the famous “Chitlin’ Circuit,” a string of entertainment venues located in the American South, East, and Midwest, which gave African American entertainers an opportunity to perform during a period of racial segregation. Asbury Park became known as a destination for both music and leisure and the music and stories of Springwood Avenue provided the foundation.

That reputation and the story of Asbury Park’s west side changed, dramatically in July 1970. During a time of civil unrest and racial tension across the country, Asbury Park also experienced several days of violence and destruction beginning on the 4th of July and Springwood Avenue was largely devastated, including businesses, homes and music venues. Although some seventeen clubs once stood along Springwood Avenue, only one remains, what was once Leo Karp’s Turf Club. In its heyday, the one-story square building, which stands at the corner of Springwood and Atkins Avenue, sat among a lively streetscape of residences and businesses and was a hotspot for music and culture, but in recent years it has become an isolated building, stripped of all signage, boarded up, and flanked only by a community garden to the south and a vacant lot to the west. Due to the precarious state of the building, AP-AMP launched a campaign to save it by transforming the former night club into a musical center for the community—a process that is still in the early stages. Cliff Johnson, a 93-year-old saxophone player who played at the club during his youth, recalled:

I was playing at the Elks...on my intermission, I would walk around the block...to the Capitol, listen to what the musicians were playing there...walk just a few steps down from the Capitol, walk into the Turf Club, check those guys out. It was like a round robin...All this was within four minutes, three venues within four minutes, and music going all the time. It was fantastic.

In addition to the Turf Club, there is another variety of cultural patrimony that is at risk of being lost along Springwood Avenue: the soundscapes and history of the local African American community. As TCLF highlighted in its Landslide 2018: Grounds for Democracy, many significant African American sites are unrecognized because they do not meet the conditions that have long defined the conventional approach to historic preservation, such as the integrity of historic structures or the stylistic elements of the built environment. Princeville, North Carolina, the first town incorporated by African Americans in the United States, is a prime example of how significant cultural landscapes can fail to gain recognition via mainstream historic preservation efforts. These and other relevant issues were the subject of a recent Q&A with Kofi Boone, an associate professor of landscape architecture at North Carolina State University’s College of Design. Like Princeville, the Springwood Avenue cultural landscape has little remaining historic fabric, but it is full of intangible cultural heritage.

Although music continued all along and helped contribute to the City’s revitalization, there has been minimal focus on the African American musical heritage that informed the music scene and played a critical role in the development of the City as a culture and arts center on the Jersey Shore. The stories and music of Springwood Avenue live in the collective memory of those who experienced it. As those who lived this history are lost to old age, the lack of documentation and celebration of Asbury Park African American’s culture can lead to a perceived and actual erasure of history and culture. Although efforts are underway, it is difficult for a visitor to Springwood Avenue today or a community member who grew up near Springwood Avenue, to get a sense of the culture and history of the community that helped shaped the City.

The AP-AMP team believes that sharing the stories through those that experienced the history is the most successful and valuable way to celebrate Asbury Park’s comprehensive history. They have prioritized outreach methods that showcase the voices, words and sounds of Springwood Avenue’s history and allow people to continue to contribute their story.

Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) is a relatively new concept among those that deal with managing change in the built environment, including the American historic preservation and design communities. ICH encompasses the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, and skills that communities, groups, and even individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage. Historic preservation has largely been the province of the built environment for as long as it has existed, so there are relatively few specific policies or procedures designed to support ICH. The UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (2003) and the Australian Burra Charter (2013) are still in their infancies and, as such, are not widely understood or utilized in America. This is particularly problematic in the digital age, when much of what constitutes contemporary life is intangible: music, television, movies, games, and the internet, for example, all shape and influence the way we live. In many ways, society has made a profound leap from the physical to the digital, but American attitudes and policies concerning ICH have yet to change.

So, while most of the buildings along Springwood Avenue are gone, there is still an opportunity to apply what we are learning from the international community about intangible forms of our culture. In 2003, 178 nations ratified UNESCO’s Convention for the Safeguarding of ICH, but the United States, along with Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, chose to abstain. The 2011 UNESCO vote that admitted Palestine as a state complicated the matter even further. Due to laws passed decades ago in America, the government was forbidden from paying its dues. The 2003 UNESCO Convention includes songs and stories under the definition of ICH, which other nations of the world have actively moved to protect via inventory systems, databases, and policies.

Currently, there are several different technologies that provide for the protection and dissemination of ICH, including open and extendable platforms that offer resources for research and education. One system, called i-Treasures, grants access to several forms of content, including images, video, audio, and text, to educational and heritage institutions. The Asbury Park African-American Music Project is partnering with Pass it Down, a digital museum platform, designed to help collect, preserve, and share stories. Another platform, called Traditional Music of the World, is a collection of in situ recordings on vinyl and CD made by ethnomusicologists of music from around the world. Unfortunately, this system doesn’t allow for online access and primarily serves as an archive. Indeed, none of these available platforms are perfect, but they do demonstrate the growing interest in ICH and the recognition in places like Asbury Park and elsewhere that ICH is a vital and irreplaceable part of our shared cultural legacy worthy of preservation.