Professor Emeritus of Architecture Marc Treib Weighs In on Potential Destruction of MARABAR (2020)

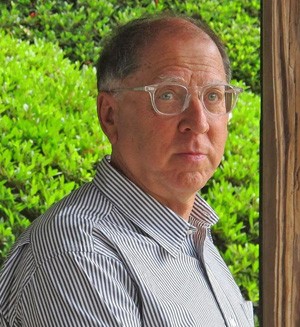

Editor’s Note: On April 3, 2020, Professor Emeritus of Architecture at the University of California Berkeley College of Environmental Design Marc Treib wrote the following letter to the District of Columbia’s Historic Preservation Review Board (HPRB), asking that body to reconsider its approval of plans that would demolish the sculpture MARABAR at the National Geographic headquarters. Completed in 1984, MARABAR is the work of celebrated artist Elyn Zimmerman, who recently spoke with TCLF about her career and the National Geographic commission in particular. After officially listing the National Geographic headquarters in its Landslide program for threatened cultural landscapes and landscape features, TCLF also requested that the HPBR revisit the case in light of information that the review board lacked when it rendered its initial decision.

Dear Sir or Madam,

I recently learned that Elyn Zimmerman’s classic work “Marabar” that defines the plaza of the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C., has been threatened with removal or demolition. I am writing in hopes that this can be prevented, that is to say, permission will not be granted for its alteration in any way. “Marabar" is a key representative of American site-specific art, elegant in its form, impressive in its use of stone, and engaging in its effects. The relation of the stones to the water trough is masterful. The play of reflective polished surfaces against the rough surfaces of the stones is engaging and mystifying, and I have personally seen many visitors spend inordinate amounts of time walking around and through the stones while tracing their movements upon the polished surfaces. It is remarkable in terms of what it is, and fascinating in terms of what it does. It is a work of particular delight to children, as they see themselves in these mirrors and smile and laugh in response.

Unlike “Marabar,” the majority of representative works of land art and site-specific art are inaccessible without considerable effort. To experience works such as Michael Heizer’s "Double Negative" in Nevada, and "Spiral Jetty" in Utah, requires both time and money, which limits their audiences. Many major site-specific art installations are located on private or corporate land, with only limited access granted the public. Happily, and in contrast, “Marabar” has been broadly available to the public. It is certainly one of the great works of the later twentieth century, and one of the few located in a city. It is a work appreciated as both art and as landscape architecture. When I first visited the site decades ago, I was so taken with the piece that I wrote about it almost immediately, and I have continued to refer to it in many subsequent publications and lectures.

I would request that before granting any permit for “Marabar’s” removal, the committee seriously consider what would be lost—an important piece of America’s art heritage—and require architectural studies to determine alternate solutions that could meet the National Geographic Society’s space needs.

Sincerely,