The Quarry Gardens at Schuyler

Located just 25 miles south of Charlottesville, Virginia, is a cultural landscape that proudly displays the hardness of its industrial past alongside the natural beauty of its native flora. The Quarry Gardens at Schuyler is the brainchild of Armand and Bernice Thieblot, who came to the area nearly three decades ago seeking respite from the fast-paced lives and careers they had built in Baltimore, Maryland. What the Thieblots found—and eventually purchased—in the sleepy hamlet of Schuyler was a large tract of land containing the remnants of soapstone quarries. After permanently relocating to the property, they transformed the abandoned site into something special—something not just for their own enjoyment but for others, too. After years of planning and work on what can be aptly descried as a labor of love, the Quarry Gardens at Schuyler is both a remarkable showcase of native plants and a repository for the history of the soapstone industry.

A Mineralogical Mecca

The quarries at the heart of gardens are the visible remnants of the so-called ‘Albemarle-Nelson Belt,’ a massive soapstone deposit that lies between the Virginia cities of Charlottesville and Lynchburg. Coursing along a southwesterly path that runs through parts of Albemarle, Nelson, Amherst, and Campbell Counties, the belt is particularly wide at Schuyler, in Nelson County, where an exposed section of the vein lays bare what is said to be a greater percentage of workable soapstone than in any other known deposit in the world.

Varying in color from bluish gray to greenish gray and brown, soapstone is a non-porous, non-absorbent, metamorphic rock with remarkable properties. Relatively soft and easily workable with even the most rudimentary tools, this stone with the soapy feel has been used from time immemorial as a medium for carving statuary, cylinder seals, and even Scarabs. Native Americans, including the Monacan and Siouan tribes in the Schuyler area, shaped it into bowls and pipes, and used it as a cooking surface. Made primarily of talc, the incredibly dense stone is acid-, alkali-, and bacteria-resistant, guaranteeing its value in the modern era, too. Its capacity to absorb and then slowly radiate large quantities of heat made it a choice material for masonry heaters, and its low conductivity meant that it could safely house high-voltage electrical equipment.

This versatile gift of nature near the banks of the Rockfish River would be Schuyler’s claim to fame. But the story began in nearby Albemarle County, where the Albemarle Soapstone Company was established in 1883 and soon began producing its “Alberene” stone, a moniker combining the name of partner James Serene and the company’s local. So great was its initial success that the small village of Johnson's Mill Gap was renamed Alberene, essentially serving as a company town that by 1900 had become home to some 250 of the company’s employees.

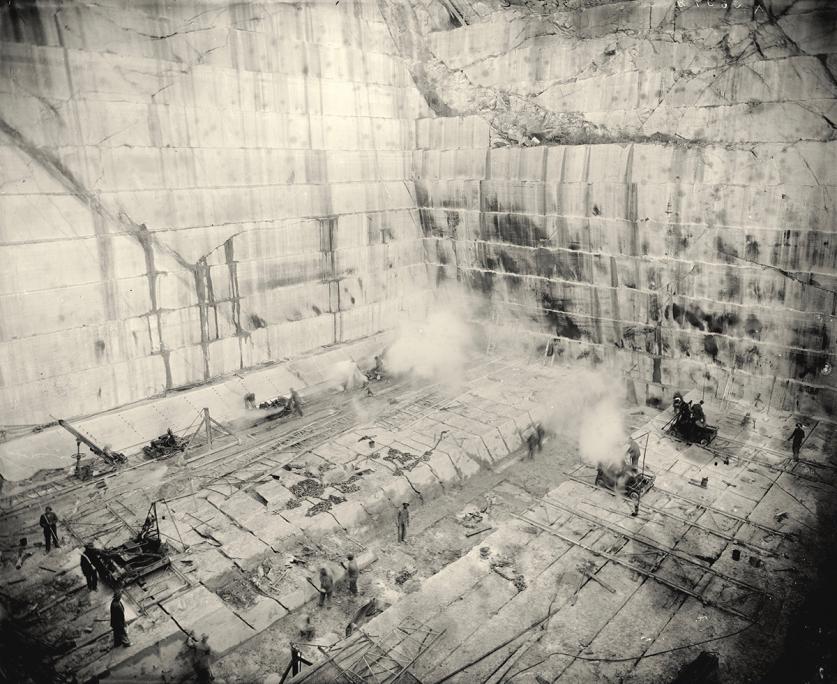

By that time, the Virginia Soapstone Company, a rival enterprise established in 1893, was operating a quarry and mill in Schuyler, which had also developed into a thriving company town. With their headquarters located just seven miles apart, the two companies merged in 1904. Four years later, when the Alberene quarries had been largely exhausted, the company’s operations moved to Schuyler, where the soapstone vein was of unprecedented dimensions—more than 2,000 feet in length and 300 feet wide.

Throughout the 1920s, the Schuyler-based Alberene Soapstone Company managed America’s largest soapstone processing plants and was one of the three largest soapstone operations in the world, taking its place alongside others in Finland and Brazil. In its heyday, the small village of Schuyler boasted more than 50 active quarries, with double that number in Nelson and Albemarle counties combined. Although the general economic malaise of the Great Depression brought a change in ownership, the company experienced a significant recovery during World War II, as it supplied products to the booming defense industry. And although a record flood devastated the Schuyler plant and ancillary facilities in September 1944, the quarries were re-opened and prospered during the 1950s.

That’s when the quarry sites on what would become the Thieblots’ property began to be mined, and quarrying activity there would continue through the 1970s. The property and its mineral rights passed into private ownership in the 1980s, although other quarry sites in Schuyler continued to be active. In 2014 Polycor purchased the Alberene Soapstone Company, and Schuyler remains the only active soapstone-quarrying area in the United States, producing a product that is now a choice material for kitchen countertops and floor tiles. But other abandoned quarry sites in Schuyler were destined to serve another purpose.

An Escape Plan with a Twist

While most of the soapstone quarries of Schuyler were winding down their production, some 200 miles to the northeast in Baltimore, Maryland, Bernice and Armand Thieblot were busy shaping an industry of their own. The couple ran the North Charles Street Design Organization, a marketing and communications firm that specializes in public relations in the burgeoning higher education sector. But having spent years building a thriving business, they began to entertain thoughts of retirement. After initially scoping possible destinations around Baltimore, the Thieblots eventually widened their search. “We found the Schuyler property in 1990 through one of those tiny ads in the back of the Wall Street Journal, under the headline ‘Paradise Found’, ” Bernice recalls.

Although set against the picturesque peaks of the Blue Ridge Mountains, the site could hardly have been described as pristine when the Thieblots discovered it. The former owners had installed a pool and a cabana, but more troublingly, the land had been used as a de facto community dumpsite where all manner of detritus, from sinks and stoves to couches and cupboards, had been discarded, as Bernice well remembers: “Much of the land had been clear-cut and abused, and parts of it were essentially a dump, but there were also two large ponds, streams, most of one side of a mountain—and many possibilities.”

The Thieblots purchased the 440-acre abandoned quarry site in 1991 and for the next two decades spent their weekends slowly cleaning and clearing the property, hauling away tons of debris by the truckload. “Incrementally, we made roads and trails, corrected drainage problems, and cleaned up choked woodlands and trash. After a while we would take houseguests to see what could be seen of the quarries. Even in their overgrown, neglected, trash-strewn state, they had a kind of majesty.”

In 2013 the couple began to reside at the Schuyler property permanently. Later that year, they visited the Butchart Gardens on Vancouver Island, in British Columbia, where former limestone quarries had been transformed into a verdant landscape. The trip proved to be inspirational: “The light went on when we visited Butchart Gardens. Those very ornamental gardens were designed to heal the land and obscure its quarrying history. We decided—for practical and environmental reasons—that we would use the “good bones” of our quarries to frame a showcase of locally native plants.”

Upon their return to Schuyler, the couple embarked on a three-year endeavor to create new public gardens set amid the unique quarried landscape. To produce the master plan for the site, they hired the Charlottesville-based Land Planning and Design Associates. In 2015 the Thieblots separated 40 acres of land for the Quarry Gardens per se, simultaneously placing some 400 acres into a Virginia Outdoors Conservation Easement in order to buffer their new Eden. The Center for Urban Habitats (CUH) was commissioned to survey the animal and plant species on site and to design and install the gardens. As work progressed, the Thieblots eventually added a 150-acre parcel adjacent to the south side of the Quarry Gardens to protect the viewshed. In 2016 the property was designated a Virginia Treasure by Governor Terry McAuliffe.

A Showcase of Native Flora Blooms

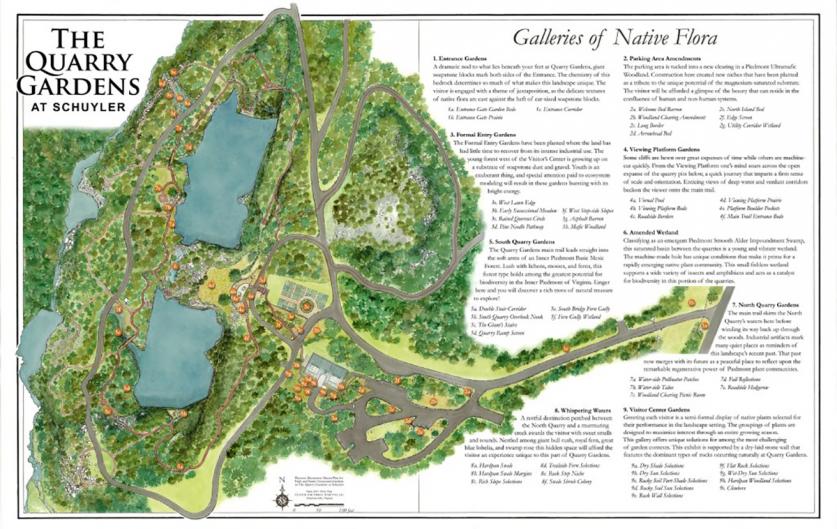

The first of several extensive surveys of the plant and animal life at the site was completed in May 2015, and others have since been made. With the results of these surveys in hand, the 40-acre parcel was divided into fourteen ecozones and seven conservation zones immediately surrounding the two pools formed by the quarry pits. The ecozones use “indicator” plants, as well as natural features in the landscape, to determine what can best grow in each zone. New plants were propagated, and the stock of indigenous flora was also increased, ensuring a mix of species that would thrive in the particular soil and microclimate of each discrete area.

The Quarry Gardens at Schuyler opened to the public in the spring of 2017 and have received a warm reception. More than 100 separate tours were conducted for 1,400 visitors in 2019 alone. The site now features some 35 galleries of native plant communities, all meticulously documented, with the information organized in databases and made available to the public online. Thanks to the rigorous surveys—the latest was made this past summer—and a considerable amount of hard work, the site now boasts the largest documented number of Virginia native plants of any botanical garden in the Commonwealth. The complete list names some 650 species of flora, 503 of which are native.

Two miles of trails have been established, allowing visitors to explore the natural beauty of the gardens and the quarries, while 163 rock stairs help them navigate the more than 60-foot-change in elevation. The property contains six different quarry sites that together form two large, rock-sided pools of water, each approximately an acre in area and 30 to 45 feet in depth. It is estimated that some 800,000 tons of soapstone were extracted from the site, with 600,000 tons of quarried stone discarded in the process. Reached via the meandering trails, the designed plant galleries include prairies, butterfly and pollinator gardens, wetlands, vernal pools, a fern gully, and a waterside talus, integrating nearly 50,000 added plants in all.

The Thieblots also established a visitor center at the site that presents exhibits on native plants, local ecosystems, and the history of the soapstone industry in Schuyler, complete with a classroom that seats up to 40 and a working model of the Nelson and Albemarle Railroad—once a key component in transporting the heavy stone to market.

The Next Transition: The Future of the Quarry Gardens

The Quarry Gardens are operated by the Quarry Gardens Foundation, a non-profit 501(c)(3) with a manifold mission that includes preserving and exhibiting relics of the soapstone quarrying industry, showcasing the native plant communities for public education and enjoyment, maintaining records of plants and animals as a resource for study, and making local plant genotypes available to others through propagation.

That ambitious agenda is coupled with a maintenance program that is in no small part aided by nature, as the plants are allowed to go to seed annually. Most of the late-season garden cleanup is delayed until spring, helping to provide food and habitat for animals during the winter months. The CUH continues to be involved in the gardens, giving advice and direction about maintenance and planting. CUH staff members also work in the garden galleries alongside volunteers who are typically either Master Gardeners or Master Naturalists. In addition to the Thieblots, who still give most of the garden tours and furnish the day-to-day care of the property, one full-time staff member maintains the forested area and the roads.

The gardens were never conceived as a money-making venture, and, according to Bernice, memberships and donations (a donation of $10 per person is suggested, but not required, upon entry) currently cover only about ten percent of the costs to maintain the site. “The area around us is not wealthy, so it’s important to us that visits to the gardens not be limited to those who can pay.”

Still in good health but now in their late 70s, the Thieblots have come to terms with the fact that the next phase of their gardens will depend on others. Although several local groups and organizations routinely spend time and energy helping out, none have the capacity to administer the site full-time. Concerns about ecosystems and plant succession have thus begun to turn to who will succeed the caretakers themselves. For now, that is a question without a clear answer.

“We’re grateful that The Quarry Gardens have given us an active retirement with much to do, much to learn, and many inspiring friends, but I don’t think we’ll get to decide their future. We know our mission and we’ve invested love and money in realizing it, but it will be up to others to determine the importance and ultimate uses of the site.”