Race and Cultural Landscapes: A Conversation With Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Editor’s note: ‘Race and Cultural Landscapes’ is a series of one-on-one conversations with thought-leaders around the nation about how issues of race and history are represented and evoked in cultural landscapes (see Part 2 and Part 3). The aim of the series is to shed light on these complex and often controversial issues via thoughtful questions and dialogue. In this first conversation in the series, Dr. Elizabeth Kryder-Reid talks with TCLF about the polarizing nature of the California mission landscapes. Her recent book, California Mission Landscapes: Race, Memory, and the Politics of Heritage (University of Minnesota Press, 2016), traces the history of the landscapes and investigates their role as deeply ideological spaces that have largely masked the consequences of colonialism.

Can you begin by giving us a thumbnail history of the California missions?

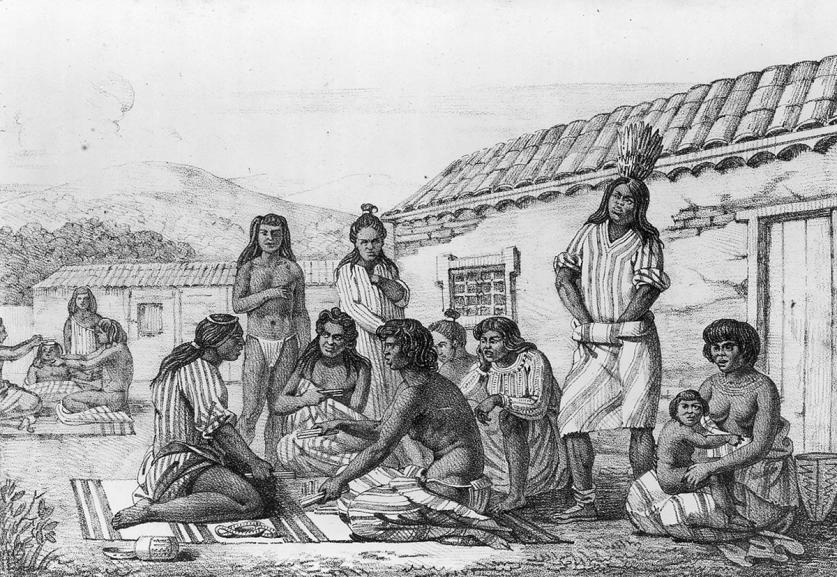

The mission story is often told as a classic rise, collapse, and rebirth narrative—the 21 Alta California missions founded by Franciscans in the name of the Spanish crown, beginning in 1769 with the first mission in San Diego and ending with the last one just north of San Francisco in 1823. The missions were intended both to “civilize” the Indigenous peoples and to claim the land for Spain. Following Mexican independence, and ultimately secularization in 1833, most missions began to decay physically in the face of earthquakes, erosion, and without the Native people’s labor to maintain them. After California became an American territory and then a state, the missions were returned to the Catholic Church in 1865 and began to be restored or reconstructed, often with quite romanticized visions of colonial times.

As you point out in your book, the mission gardens are anachronistic (the first one was constructed in 1872, long after the missions ceased to function as colonial outposts), so what was the initial impetus to create them?

As with many re-imaginings of the past, the motives were actually quite complex, although they all can be understood as part of the broader settler colonial narratives in which the loss of Native territories and the oppression of the Native people under Spanish colonialism and of American rule are downplayed, and, instead, we see the story as the beginnings of civilization in a preordained “New Eden.” Of course, those motivations were rarely explicit and may not even have been conscious for the people designing the mission gardens in the twentieth century. There is also a subtle but pervasive racial motivation in the mission landscape history. From Father Romo’s first garden at Santa Barbara through the CCC debates at La Purisima, there was an impulse to reference a distinctly European tradition, rather than locate the missions historically and culturally in Native American or Mexican practices. The modifications of the mission landscapes over time reveal different versions of that Mediterranean ideal, as parishioners, volunteers, donors, monks, curators, and parish administrators shaped the spaces to their own needs.

The missions have been restored according to various historical standards, including those of the Civilian Conservation Corps. Has this made a significant difference in the way history is presented at the various missions?

I think that while there have been standards applied to the mission architectural restorations, the development of the landscapes over time have been much more idiosyncratic. For me this makes them even more fascinating – there were no historic preservation guidelines or mandates, and yet there is a version of a mission garden at every mission, even those such as Mission Santa Cruz that has been reconstructed at a reduced scale. These mission gardens are cultural productions and they reveal the incredibly rich and varied meanings of the mission over time.

At Mission Santa Barbara, the central patio that contains the (invented) mission garden was, in fact, a work space when the mission was active as such. How should that space be represented to visitors today?

This is a tricky question, and it’s not unique to the California missions (Colonial Willimsburg, for example, wrestles with this question). One challenge is that an 1872 garden is one of the oldest extant gardens in the western United States, if not the oldest, and it therefore has historical significance in its own right, even if it is a Colonial Revival garden. At the same time, the missions are central to the painful and often contested history of colonization and the cultural and physical harm done to Native peoples there. Thousands of Native Californians were buried on these grounds, and many Native people see them as sites of genocide. In her critique, Deborah Miranda has pointed out the problematic study of the missions in fourth-grade curricula by imagining asking students to build popsicle-stick models of places with a similar history of violence and oppression, such as concentration camps and slave plantations. The mission gardens are subtler, but they essentially present the same aestheticized effacement of colonization and its enduring consequences for Native people. I think digital tools can be effective in peeling back layers over time and revealing what no longer exists. Models that use dialogue to help people come to understand divergent perspectives are also a good start.

This raises the question of how the Native peoples themselves are represented in the landscapes today—what is your view about that?

One of the first points to make is that California Native people are and have always been incredibly diverse, linguistically and culturally. Their lived experiences and their views of the missions are similarly wide ranging. Some feel a strong historical connection to the missions through faith traditions or personal and family history. For others the missions are profoundly painful places. So, the question of how Native peoples are represented must account for that range of experiences and be able to include the complexities and contradictions of the missions in acknowledging both the agency of Native Californians and the clearly oppressive power dynamics of Spanish colonization. Deana Dartt has shown how, in mission museums, Native peoples are represented in a pre-contact "frozen past," while the Franciscans are presented as the benevolent bringers of salvation and civilization. She also notes the failure of most exhibits to tell the stories of the violent persecution and racist practices of the 1850s and 1860s, during early California statehood, and the erasure of present-day Native people from the narratives. Some sites, such as La Purisima, which is run by the California State Parks system, have recently remodeled their visitor’s centers, and the new interpretations are more inclusive. But the majority of the missions are administered as active Catholic parishes, and their interpretation generally shies away from a critique of the Church's role in colonizing California.

In your book, you wrote that the mission landscapes, as heritage sites, could be used to address past injustices. Should that be the primary objective of any interpretive program at these sites?

The missions are so complicated and multivalent that they have a wide range of important stories to tell and conversations to host. But any program must, I believe, acknowledge that they are inherently Native landscapes and must acknowledge those ancestors and their descendants.

How, then, do you represent the presence of Native peoples in the landscape without objectifying them?

Great question, and a perennial challenge for museum professionals. I think a critical strategy is including Native voice, and this is another instance when digital media can be a powerful tool. Audio recordings, such as those available to visitors at Mission San Juan Capistrano, can both communicate Indigenous perspectives and humanize the mission history. Native artists such as L. Frank and James Luna have created work that challenges and provokes critical commentary on the mission past.

To play the devil’s advocate, if we expect the mission landscapes to (paraphrasing from your book) address racial injustice, transcend divisions, and include the viewpoints of multiple curatorial authorities, how do we avoid ending up with just a “panoply of stuff.”

I would argue that all landscapes are palimpsests—layers upon layers of physical changes and changing meanings over time. Cultural landscapes are ideally positioned to invite people to explore those changes, to think about what they mean, and to encourage them to make connections with current social issues. Colonial Williamsburg, Mount Vernon, Middleton Plantation—all of these are examples of richly layered sites that have grappled with their contested histories by engaging people in their complexities and contradictions. They have been catalysts for addressing injustice and still retain the integrity of their historic spaces.

Given that various institutions administer the missions, including, as you’ve noted, the Catholic Church, do you hold out hope that their interpretive programs will reflect that kind of complexity?

I actually do. Mission San Gabriel has a long tradition of working with the marginalized in their neighborhood, and they’ve worked with the Gabrielino-Tongva when they rededicated a memorial and built a reconstructed traditional dwelling. Archaeologists at Santa Clara are creating a rigorous and complex interpretation of mission life. Andrew Galvan, curator of Mission Dolores in San Francisco and descendant of an Alta California Mission Indian baptized at the mission, has worked to develop programs that account for the complexity and trauma of the mission past, as well as account for their role in California history. It’s hard work and there is a great deal of resistance. My guess is that artists will lead the way, as they have at places like Eastern State Penitentiary and with work such as Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in which the power of the visual work both acknowledges wounds and invites reflection.

So, there’s been progress with new programming, but what about elements already in the landscapes that perpetuate a false narrative of colonization—one thinks, for example, of the many sculptures of Father Serra and the Indian Boy. Should those be removed?

Another thought-provoking question. Despite the protests at Serra's canonization, including decapitating a statue in Monterey and vandalizing others, he continues to be revered and beloved by many. He is a polarizing figure, revered as both an historical figure in California history and as an exemplar of faith and sacrifice. The unfortunate reality of missionization is that both are true—people of sincere faith who made great sacrifices to do what they saw as God's work also wrought great harm. The memory practices of the missions have tended to emphasize the former over the latter, and often, as with these statues, premised on paternalistic, colonial ways of thinking and seeing. I would love to see the representations of Serra with an Indian boy used to invite viewers to question what is being represented and why. The San Fernando sculpture is in a city park and the one at Mission San Juan Capistrano is managed by a not-for-profit. Some simple questions asking people about what they are seeing and what they think it represents would be an interesting experiment in critical heritage interpretation.

We’re having this conversation against the backdrop of a national controversy about removing Confederate monuments from public spaces. Why is it, do you think, that there seems to be less controversy about public monuments commemorating those responsible for violence against Native Americans?

The conversation about the Confederate monuments is deeply connected with the enduring racial violence and injustice in our country rooted in our history of slavery. Although debates about Columbus Day are beginning to gain traction, Native American history is marginalized in ways that the history of slavery and Jim Crow don't have to contend with. Studies show that many people don't know Native Americans still exist and how their communities have changed and thrived. They think of them instead as a people "frozen in time," and exhibits often perpetuate these notions by presenting the "prehistory" of Native peoples, glossing over histories of colonization and Indian removal and ignoring contemporary cultures. It's not surprising that public monuments don't evoke the same reaction if people don't know the history or have empathy for Native communities.

Elizabeth Kryder-Reid is professor of anthropology and museum studies at the Indiana University School of Liberal Arts, IUPUI, where she also directs the Cultural Heritage Research Center.