Race & Space Convos III: Commemoration

Editor's note: This essay is derived from introductory remarks made by Charles A. Birnbaum, President and CEO of The Cultural Landscape Foundation, during Race and Space Conversations III.

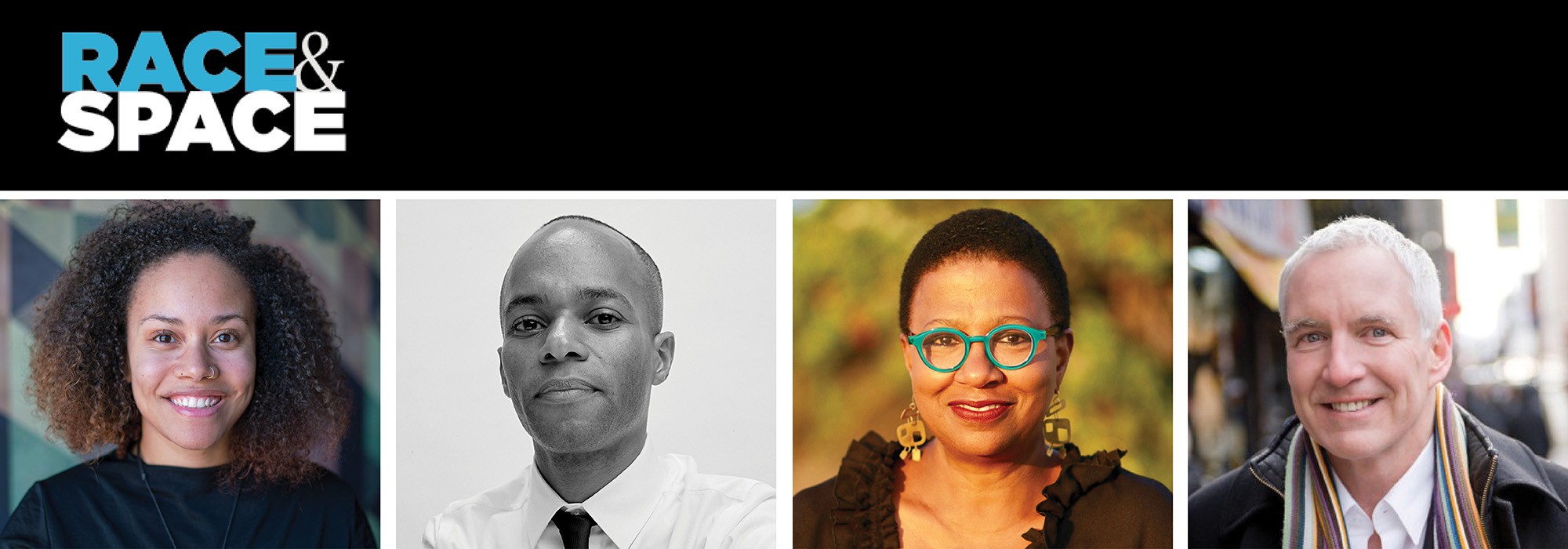

How do cultural landscapes shape our public memory, and how do design decisions affect that process of commemoration? This Race and Space Conversation, the third in The Cultural Landscape Foundation’s (TCLF) ongoing series, is happening as we are having a national reckoning about memorials to the Confederacy and slaveholders, which are being taken down in city parks, university campuses, and elsewhere. The program (video recording below), featured panelists Justin Garrett Moore, the inaugural program officer for the Humanities in Place program at the Mellon Foundation; cultural projects consultant Peggy King Jorde, the force behind the creation of the African Burial Ground National Memorial and Interpretive Center in New York City (click here for related content about King Jorde); and Jha D Amazi, Director of the Public Memory and Memorials Lab at MASS Design Group, were joined by moderator James Russell, a critic and journalist who has written extensively about memorials.

The artist Isamu Noguchi characterized memorials as “democratic acts of un-forgetting,” according to Spencer Bailey’s in-depth essay “Memorial Making.” “Un-forgetting” can be empowering, debilitating, cathartic, revelatory, reparative … there are so many implications of “un-forgetting.” When creating or conserving memorial landscapes, what aesthetic, historical, cultural, social, and political issues are artists, designers, activists, historians, witnesses, communities, and other stakeholders navigating?

In Richmond, Virginia, we’re seeing an “un-forgetting” of the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground; in the nineteenth century it was the nation’s largest burial site for freed and enslaved African Americans with more than 22,000 interments. It’s one of the sites featured in our thematic Landslide report and exhibition from 2021. Today it’s unrecognizable, a palimpsest of abuse; but one descendant, Lenora McQueen, is making it visible; and thanks to a broad coalition of advocates and stakeholders it was recently listed in the National Register of Historic Places. However, there remain plans to put high speed rail lines through remnants of the site.

This issue of commemoration in a site as rich, messy, complicated, abused, and memory laden as Shockoe raises a whole host of questions. Recently, panelist Justin Garrett Moore raised a foundational one: “What makes a history or a place significant or not”? He’s right. Who gets to decide?

What are the roles and functions of memorials? In an interview on PBS with Bill Moyers twenty years ago, architect and sculptor Maya Lin said their “function isn't like a physical function, like a house is to shelter you. It's a very conceptual, symbolic function.” Where should they go, and what is a site’s carrying capacity based on what happened there, those affected in the community, the location’s spatial and/or design integrity, the authenticity and condition of extant fabric (for example, has the site suffered purposeful erasure), and what about its setting? All these elements can elevate and frame our individual and collective engagements and experiences.

This “power of place,” to cite the title of Dolores Hayden’s groundbreaking book of 1997, is at the core of a cultural landscape. Hayden talks about “new models of collaborations between professionals and communities, as well as new alliances among practitioners concerned with urban landscape history.” She notes “Artists and designers are also active in the public work of connecting memory into the built fabric of the city. Their interventions in the urban landscape … can strengthen urban storytelling and enhance citizens’ interest in history.” Is this what anchors a pilgrimage site like the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama?

What makes for an apt memorial? The former Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne offered this cautionary lament: “These days we see the symbolic shorthand that art and architecture have always relied on to deal with violence and tragedy as wildly insufficient … Instead, we’ve embraced some crowd-pleasing mixture of authenticity, easily digested narrative and insta-history. We want to see and touch the Real Thing, and we want somebody to explain to us what the Real Thing means.”

Lastly, what about the role of technology? During an American Academy in Rome program on “Ethics in Public Art,” Justin Garrett Moore talked about Kinfolk, an intriguing project of an organization called Movers & Shakers that developed an augmented reality set of monuments. How do these innovations forge human connections to reveal a site’s “power of place”?

Panelist Peggy King Jorde’s website says, “it matters how we choose to remember.” When asked what that meant, she said: “As we live and breathe, so we remember. How we remember our forebears matters because their lives and legacy matter. We are their ‘unfinished business.’

In this Race and Space Conversation, our panelists discuss how stakeholders at all levels – from community members, activists, and artists to landscape architects, city planners, and funders – are reckoning with the “unfinished business” of commemoration in our cultural landscapes.