Ralph Dalton Cornell Biography

Ralph Dalton Cornell was born in Holdrege, Nebraska, on January 11, 1890. When Cornell was 18 his family relocated to California to take advantage of the anticipated eucalyptus boom on the Western frontier. His father’s business venture collapsed in the failed eucalyptus market, but Cornell already felt drawn to study and practice in California, which he would do throughout most of his life.

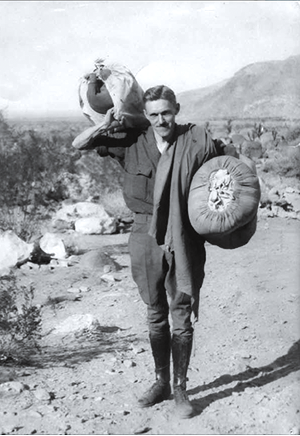

In 1909, Cornell began working his way through Pomona College, where he enrolled in a botany class led by Professor Charles Fuller Baker. Cornell attributed Baker with being a “man-maker,” having directed Cornell’s interests in gathering plants to develop his own herbarium and in documenting design suggestions for residential “plot plans.” Cornell experimented with photography and published articles with leading biologists in the Pomona College Journal of Economic Botany as Applied to Subtropical Horticulture, which attested to the value of agricultural plants, street trees, and urban park space in Southern California. He spent summers on “agricultural safari” in the desert, reporting on development and planting date offshoots. Cornell left school from 1911 to 1912 and worked on a local subdivision, but returned to complete his B.A., Phi Beta Kappa and summa cum laude, in 1914.

With recommendation from Baker and $1100 from his own lucrative endeavors in avocado propagation, Cornell began graduate studies in landscape architecture at Harvard University in 1914. After earning his M.L.A. in 1917, Cornell declined an offer from the Olmsted Brothers firm in favor of a $10 wage difference per month with Harries & Hall Architects in Toronto. Soon thereafter, Cornell served in Army combat with the 91st Division in Belgium and France but remained committed to his professional calling, collecting seeds and writing home to describe the wildflowers in the foreign countryside.

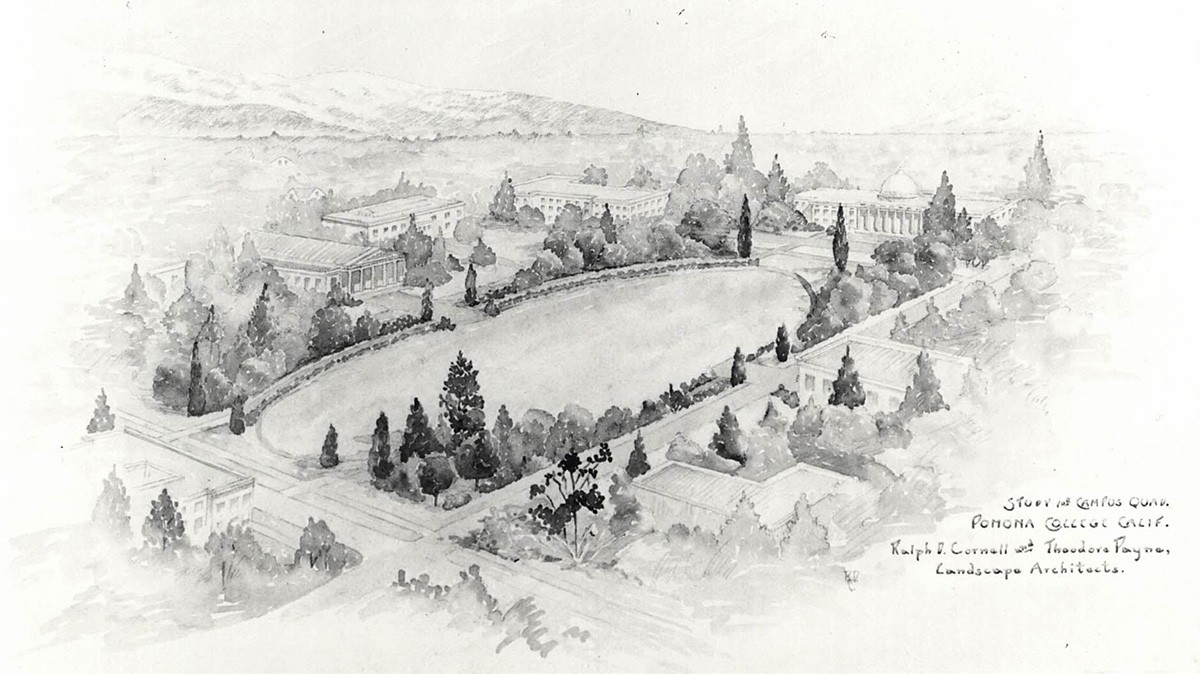

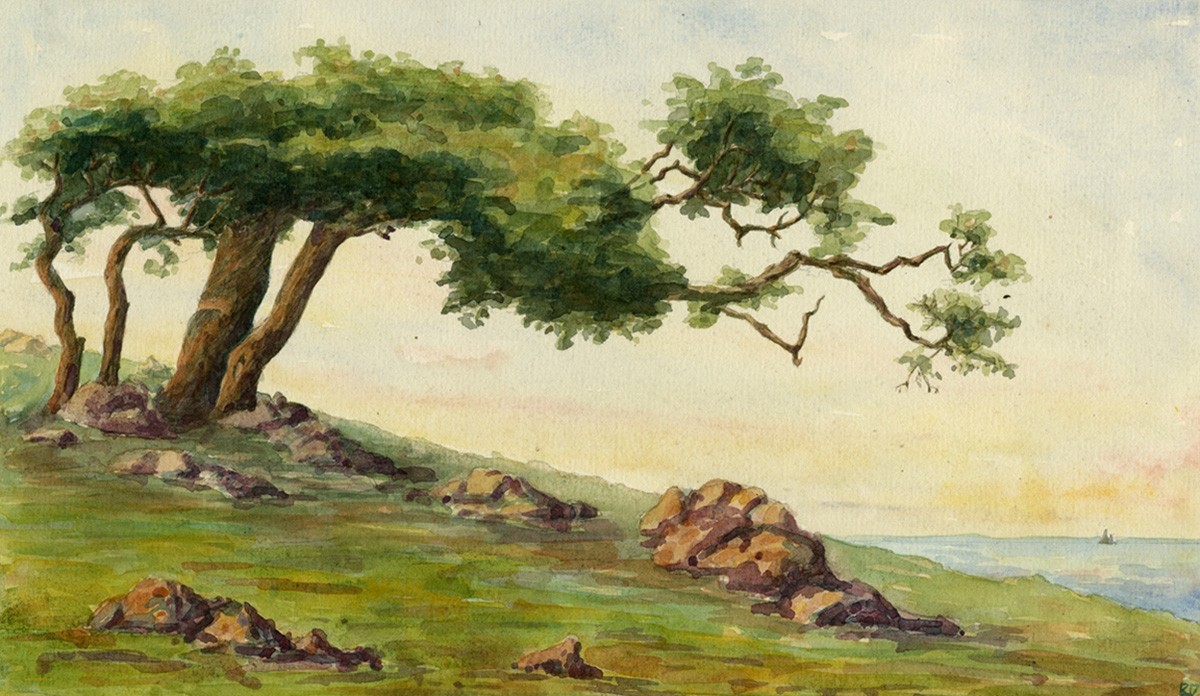

In 1919, Cornell returned to open one of the first professional landscape architecture firms in Los Angeles. His first commission was with Pomona College, where he worked on retainer for more than 23 years and ultimately completed the vision of a “campus in a garden.” At Pomona he made recommendations for unprecedented funding to employ a large quadrangle, a series of walkways, and extended vistas with carefully articulated moments of terminus. Upon partnering with native plant pioneer Theodore Payne, he designed a few small regional parks and created several master plans for Torrey Pines State Preserve that championed design restraint, thoughtful indigenous plantings, and preservation of the native landscape as a public park and a cultural necessity for posterity.

From 1924 to 1933, Cornell was a junior partner with Wilbur Cook and George Hall, local experts in city and master planning whose work echoed the City Beautiful Movement. Among his most distinguished work, Cornell secured another long-term campus planning commission in 1928 with the University of Hawaii; completed a redesign of Beverly Gardens, the nationally-acclaimed 23-block strip park in Beverly Hills; and successfully integrated existing historic trees into the 1931 restoration of the historic grounds at the Rancho Los Cerritos adobe, which later became a National Historic Landmark.

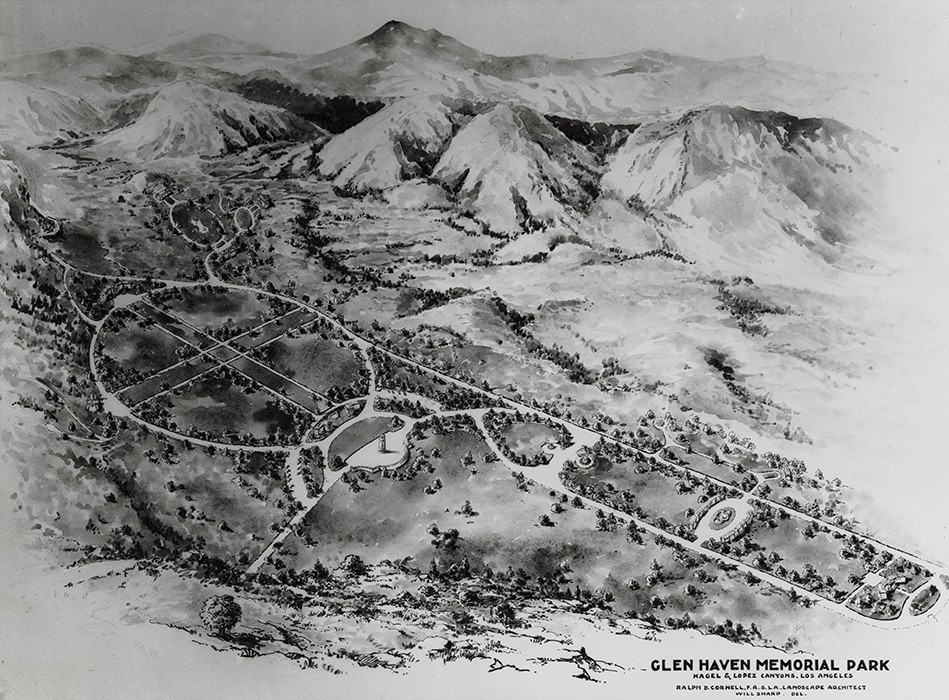

As the stock market crashed and another partnership dissolved, Cornell again went into practice for himself, establishing one of the only firms to continuously practice throughout the Great Depression. From 1933 to 1955, he demonstrated wide-ranging capacities in designing military encampments and over 50 federal wartime housing projects. Cornell was prolific: he developed subdivisions; designed cemeteries and large-scale city parks; planned two decades of national garden shows; created intimate gardens in the desert, on movie sets, and for the blind; hosted radio broadcasts; lectured; wrote countless articles; and published his 1938 book, Conspicuous California Plants. In 1937, Cornell began his third lifelong college campus commission with UCLA. He created a cohesive master plan that unified spatially and architecturally disparate academic buildings, developed a central axis for the campus, designed a series of distinct park spaces, and created the illusion of endless vistas in an otherwise congested urban setting.

In 1955, Cornell became senior partner in collaboration with Samuel Bridgers and Howard Troller, and later JereHazlett. The firm had a strong civic presence in Los Angeles, most notably designing the Civic Center Mall and the Music Center, as well as several City and County buildings. Cornell, Bridgers, and Troller additionally worked on city and college layouts, cemeteries, luxury hotels, industrial complexes, and recreational facilities. As Cornell’s role shifted to project supervision, he delved further into his passion for photography and the collection of color plant photos, which were ultimately published as a comprehensive guidebook entitled Flowering Plants in the Landscape. He never officially retired from practice.

Cornell pioneered ideas about preserving native plants and original landscapes, and championed the necessity of green space for truth, enlightenment, and refreshment of the soul. He was a scholar of Thoreau and Emerson, exhibited many values shared withpredecessors William Robinson and Jens Jensen, and challenged the next generation of landscape architects,as noted by Ruth Shellhorn and Thomas Church. He began to rebel against Beaux-Arts formalism before Modernism was truly present at the design academies. In Southern California, Cornell was at the center of a small group of landscape architects, along with Edward Huntsman-Trout, who anticipated rapid urbanization and influenced a regional style that embraced the genuine nature of the area. These designers were able to borrow Old World tradition and introduce Modernist elements together in California, employing principles of symmetry and refinement against a dramatic natural backdrop with thoughtful consideration of space rather than ornament. They encouraged a better understanding of native ecology and landscape as a system and designed for both function and efficiency. As an individual, Cornell promoted conservation of both typical and remarkable landscapes of Southern California, quietly ensuring the longevity of his vision of civic beautification with solid botanical knowledge, intense curiosity, and intentional reserve. Cornell’s work endures as a testament to why his colleagues referred to him as the “dean of landscape architects.” A Fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects, Cornell was granted an honorary doctorate by UCLA; he passed away in April 1972, two months before he could receive it.