A Red-Letter Year for Women, but Not for Their Art

There will always be threats to significant designed landscapes and landscape features (the latter include monuments, memorials, and site-specific installations), but in 2020, which marks the centennial of women achieving the right to vote in the United States, the threats to works by women are particularly notable. In Milton, Massachusetts, a 1920s-era landscape by the renowned practitioner Ellen Shipman is slated for demolition to make way for housing units and 180 parking spaces. In Savannah, Georgia, a landscape designed by Clermont Lee, one of the first women licensed to practice landscape architecture in the State of Georgia, and the first licensed landscape architect, male or female, to practice in the City of Savannah, was recently demolished. Lee worked on the project off and on for some 50 years, beginning in the mid-1950s. Unfortunately, her work was not subject to any meaningful oversight or review, despite being located within one of the most rigorously protected historic districts in the nation. Yet another irony is that the landscape in question was the garden Lee designed and refined over five decades for the Juliette Gordon Low Birthplace, the home of the founder of the Girl Scouts of America. Why did the Girl Scouts sacrifice the work of such a pioneering woman? They wanted more event space.

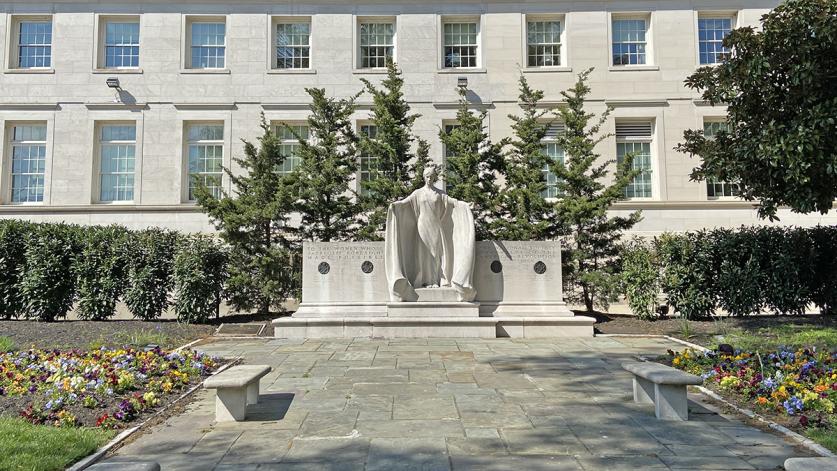

A similar situation is playing out in Washington, D.C., where a site-specific installation on the campus of the revered National Geographic is now facing erasure. To provide some context, according to Wikipedia, there are roughly 290 publicly accessible monuments, memorials, sculptural installations, and works of sculpture in Washington, D.C.’s, Ward 2 (which includes much of the city’s downtown, the National Mall, and Georgetown). Women artists designed fewer than ten percent of those works. These include the Vietnam Memorial by Maya Lin, the Vietnam Women’s Memorial by Glenna Goodacre, who recently passed away, and the Founders Monument at the Daughters of the American Revolution headquarters by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney.

Add to that short list the sculptural installation called MARABAR, by the eminent artist Elyn Zimmerman, conceived specifically for the central plaza of the National Geographic headquarters. Although the work is widely acclaimed, it may be sacrificed for the sake of a renovated entryway and new pavilion. The focal point of the installation is a rectangular reflecting pool (6 x 60 ft.) set amid five mahogany-colored granite boulders, three of which have highly polished and reflective surfaces, mirroring one another across the pool. The work was commissioned in conjunction with a replacement wing designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). The building was built in 1981, and MARABAR was completed three years later. National Geographic first contacted famed artist Isamu Noguchi about creating the plaza installation. When plans to engage Noguchi didn’t work out, SOM principal David Childs suggested Michael Heizer and Elyn Zimmerman, with the commission ultimately going to the latter.

Scholars and critics alike have written about the importance of MARABAR. Adam Weinberg, director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, calls it a “masterpiece” and describes Zimmerman as “one of the great public artists of her generation.” According to Marc Treib, professor of architecture emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley, “‘Marabar’ is a key representative of American site-specific art, elegant in its form, impressive in its use of stone, and engaging in its effects.” Treib has also praised MARABAR as “certainly one of the great works of the later twentieth century.” Penny Balkin Bach, executive director and chief curator of the Association for Public Art, has written that the artist’s “large-scale artworks have contributed to and defined the use of natural elements in the field of outdoor sculpture and public art.” David Childs, now chairman emeritus of SOM, recently wrote: “Washington is noted for its public art, and Marabar is one of its finest examples.”

Where does National Geographic stand on the prospect of erasing what so many clearly see as a significant work of art? So far, the vaunted scientific and educational organization seems to be in denial about its own proposal. Angelo Grima, National Geographic’s executive vice president and general counsel, has taken issue with the claim that the plaza renovation would actually lead to the “destruction” of the work, writing in an April 8, 2020, letter to The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) that National Geographic had contacted Zimmerman in 2017 and “offered to facilitate relocation of the sculpture’s granite stones, some of which are quite massive.” This, of course, ignores the fact that MARABAR is a site-specific work and that dismembering it and relocating the large boulders would constitute its destruction. What’s especially disconcerting is that a revered institution that educates us about what is culturally significant has determined that this work is culturally unimportant, irrelevant, and incompatible with its plans.

One can’t help but wonder whether National Geographic would proceed with its demolition plans if MARABAR were designed by a famous male artist like Isamu Noguchi.