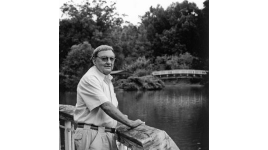

Remembering Esteemed Landscape Architect Richard Bell

EDITOR’S NOTE: TCLF marks the passing of landscape architect Richard Bell, who died peacefully at home in the hours just before noon on Monday, March 16, 2020, at the age of 91. A version of the following biographical essay, authored by Rodney L. Swink, appeared in TCLF’s Shaping the Postwar Landscape, published in 2018.

Richard Chevalier “Dick” Bell was born on April 10, 1928, in Manteo, North Carolina. His father, Englishman Albert Quentin “Bert” Bell, immigrated to Canada in 1911 and then, in 1919, to Elizabeth City, North Carolina, where he met and eventually married Maud Price. Sharing a love of plants, the couple opened and ran a nursery in addition to their regular jobs. In 1933 the Bells moved to Roanoke Island, where Bert worked for the Works Progress Administration. He took on occasional projects as a designer and builder, including a camp for the Civilian Conservation Corps, and he took correspondence courses in surveying and landscape design.

Dick Bell enrolled at North Carolina State College (now University) in 1945, originally studying chemical engineering despite his family’s background in plants, design, and construction. On his father’s advice, Bell switched to landscape architecture in his sophomore year, studying under Edwin Gil Thurlow and Lawrence Enersen before graduating in 1950. Thurlow triggered Bell’s passion for landscape architecture, and Enersen, who was trained in both landscape architecture and architecture, taught Bell to understand a project from an architect’s perspective. Bell got his first real job in the field from Professor Morley Jeffers Williams, who was working on a master plan for the college’s campus and hired Bell to make color renderings. The work helped pay Bell’s tuition and sparked his interest in campus planning.

It was also Professor Williams who alerted Bell to the Rome Prize, which North Carolina State graduate George Patton had won in 1948. When Bell applied in 1950, the jury, comprising Michael Rapuano, Ralph Griswold, Alfred Geiffert, Jr., Richard K. Webel, and Gilmore David Clarke, made clear to him their interest in choosing someone who would establish landscape architecture in the American South. Bell assured them he would be that person, but he did not win the Rome Prize until one year later, in 1951. In the meantime, he accepted an apprenticeship with the office of Simonds and Simonds in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. There he absorbed the design philosophy of John Simonds and Philip Simonds’s methods for making working drawings and construction details. Bell then spent two years traveling throughout Europe, Central Asia, and Africa, exploring the arts and studying the planning and design of cities and civilizations.

Upon returning from his fellowship in 1953, he apprenticed in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with Frederic Stresau, a landscape architect noted for his refined aesthetics and extensive plant knowledge. Bell was hired to complement Stresau’s more naturalistic creations with a modernist approach to design. While there, Bell worked on a design for the parterre gardens for the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach, designed by architect Morris Lapidus. Stresau also placed great emphasis on the value of professional registration for landscape architects, something Bell took to heart and drew upon years later in North Carolina.

In 1955 Bell founded Godwin and Bell Landscape Architects with James A. Godwin in Raleigh, North Carolina. Much of their work focused on urban renewal and public housing, but Bell became increasingly disturbed by the outcomes of many urban-renewal projects and left the firm in 1961 to pursue contemporary design and to work with members of allied professions to advance the greater landscape industry. Bell’s new firm was anchored at Water Garden, the home and office complex that he and his wife, Mary Jo Harris Bell, developed over fourteen years, beginning in 1956. Covering eleven acres, the modernist Water Garden was their residence and studio, but it also became an office park and cultural arts center. Its mix of pines, hardwoods, and wetlands served as a laboratory for Bell to test plants and planting methods; he was among the first in North Carolina to use native plants in residential landscapes. Water Garden also served as the testing grounds for the North Carolina Sedimentation and Erosion Control Law, established in 1973.

In a career that spanned more than 50 years, Bell completed more than 2,000 projects, from residences to public parks, university master plans, and island resorts. He worked on campus master plans for North Carolina State University, Meredith College, Peace College, Appalachian State University, Western Carolina University, Fayetteville State University, and St. Mary’s School in Raleigh. Among his most notable campus designs were the central plaza known as The Brickyard on the North Carolina State University campus and the McIver Amphitheater and Meredith Lake at Meredith College. He also designed the grounds and interior gardens of the North Carolina Legislative Building with architects Edward Durell Stone, Sr., and Holloway-Reeves; developed master plans for Pilot Mountain and Stone Mountain State Parks for the North Carolina State Parks Department; designed a master plan and site improvements for Raleigh’s historic Pullen Park; and developed master plans for Figure Eight Island and Hammocks Beach Island (now Hammock’s Beach State Park) on the North Carolina coast.

Bell led the creation of the North Carolina chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA), and in 1969, recalling Stresau’s philosophy, he was instrumental in establishing the landscape- architecture registration law in that state, becoming the first appointee to the North Carolina Board of Landscape Architects. In 1990 Bell became a Fellow of the ASLA, and in that same year he was joined by his daughter Sharon and her husband, Dennis Glazener, to form Bell-Glazener Design Group. Among their important projects were the Raleigh Moore Square transit facility and parking deck and, what Bell considered to be one of his most notable achievements, work on Guilford College in Greensboro, North Carolina. To avert a plan to build a highway through the college’s campus, Bell designed an alternative 22-mile-long boulevard that is considered to be the only traffic corridor in North Carolina whose design, by a landscape architect, was primarily determined by environmental criteria. Bell’s passionate advocacy for environmentally sensitive site design and his collaboration with allied professionals have had a profound impact on the development of landscape architecture in North Carolina and the American South. In recognition of his exceptional career, he was awarded the ASLA Medal in 2014.