Remembering Grant Jones

Grant Jones, an influential, award-winning landscape architect and former Board Member of The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF), passed away on June 21, 2021, at the age of 82 in Oroville, Washington.

Jones was born August 29, 1938, near Seattle. According to the Seattle Times, he grew up “on a farm that his Grandad took care of. He was a tide-flat beach kid on the largest brackish estuary in North America. His mentors were Dungeness crabs, cockles, lingcod, and hug rays called skates. This early, intimate connection with his home landscape would shape his language and his love of nature.” His father, Victor, was an architect and his mother, Ione, encouraged his love of the natural world.

Jones received a bachelor’s degree in architecture from the University of Washington (UW) in 1961. He pursued graduate studies in poetry with Theodore Roethke before entering Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) where he received a master’s in landscape architecture. He was awarded Harvard's prestigious Frederick Sheldon Traveling Fellowship in 1966 that allowed Jones to spend two years traveling Europe and South America.

Additional details of Jones’ life and the firm he established in 1969 with his first wife, architect Ilze Jones, along with their numerous projects and awards, including the American Society of Landscape Architects first Firm of the Year Award (2003), are recounted elsewhere and well worth reading. Clair Enlow in Living Place: The Architecture and Landscape Architecture of Jones & Jones (Spacemaker Press, 2006) captured the essence of the firm he established with fellow principals Ilze and Johnpaul Jones:

Jones & Jones has helped to create a language of place, reaching beyond the traditional boundaries of the architecture and landscape architecture professions, and bringing other disciplines inside the circle … [they have] mixed science and art in a unique practice. So far, the process has taken place in zoos and botanical gardens, rivers, roads and urban places from Singapore to Seattle to Washington, D.C., to Jerusalem. In each of these areas of practice, the firm has changed the way a project type is addressed.

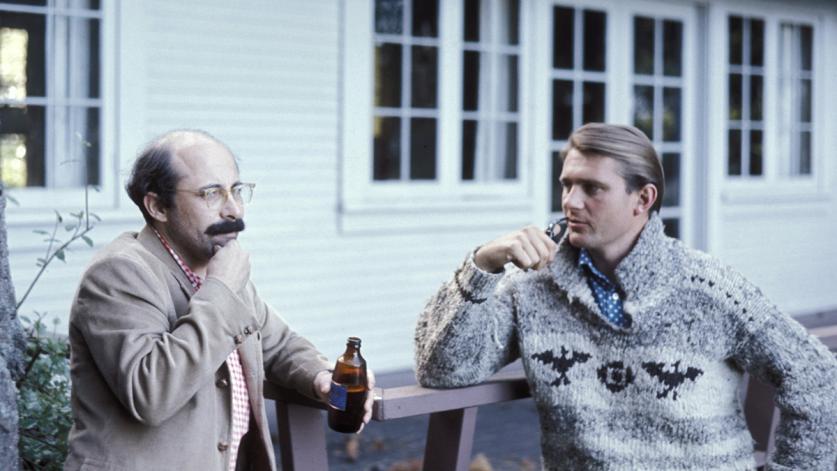

We wanted to present Grant in his own words, which are deft, clever, amusing and piquant, and reveal his distinct read on his surroundings and the people with whom he interacted. They are taken from his May 2014 recollections that accompany the Pioneers oral history with his teacher and mentor, landscape architect Richard Haag:

I discovered landscape architecture through the good fortune of meeting Richard Haag, a lecturer and visiting design critic in my architectural studio at the UW in 1959. His stagecraft captured our hearts during those last two years of architecture and after graduation. Growing up as a child and student of the tide flats, I brought my passion for nature to his office on Fuhrman Avenue, experiencing first hand Richard’s dedicated advocacy for the landscape as well as his guerilla tactics out in the community. Technically I was a rebel of the Beat Generation, but I had come through a liberal education at the Lakeside School one of the best prep schools in the country. I had learned to write and think as a natural act of free thought and to challenge what my generation referred as “The Establishment.”

But Haag’s blend of Kentucky farmer cunning and Japanese folkways-Zen lifted me to another level. He also opened the doors to Harvard where his close friend Hideo Sasaki was Chair. The GSD was an emporium of creative action where landscape architecture was the father of planning and was equal to architecture. No designer had won the Sheldon Fellowship since Thomas Church. Professor Hornbeck encouraged me to apply for the Sheldon and to our great surprise; I won it and began preparations for a year and a half of research in South America and Western Europe.

But before Haag, architects told us that the only thing landscape architects did was plant shrubs around buildings. Haag corrected that narrow outlook by showing us that landscape architects designed with all of nature in mind. The whole landscape was their medium because they had to lay out parks and to design the roads within them, lay out new communities and school campuses, botanical gardens, even zoos. Richard’s office library was brimming with interesting books. After hours I taught myself plants, memorizing thousands of Latin scientific names. I stayed late and read stories about the great plant hunters of the Nineteenth century like Wilson and I read Loren Eiseley’s magnificent essays on nature and evolution, as well as Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac. I designed a few residential gardens and small parks for the city. Eventually I helped manage a huge job that Richard brought into the office in 1962, to convert the Seattle World’s Fairgrounds into a downtown park and civic center.

By now my tide flats had become for me an even more powerful symbol, my own version of Northwest mysticism; a term used locally by regional artists such as Mark Tobey, Morris Graves and Richard Gilkey. My sources would include the whole landscape: clouds, misty river mouths, salt flats and driftwood marshes beneath glacial-till sea bluffs and swirling kelp beds ringing windswept rocky islands with stunted fir trees shaped like gusts of wind.

Ted Roethke was an equally powerful shaman. After graduating in Architecture, confidence to write and think led me to get into Ted Roethke’s exclusive Verse Writing class for two more years. Roethke had a passion for giving a voice to the landscape with craftsmanship and to be revelatory with physicality and excitement for life’s forces. Roethke also demanded our deep study of the Old Masters along with contemporary revolutionaries from Britain and the Americas, while at the same time requiring two poems a week written in our own voice, something that Ted hammered into each of us relentlessly, like a blacksmith shoeing wild horses with iron from their own wild hills.

From now on when I moved through an old or new landscape, I would become connected to it. I would approach its unfolding rooms like a polite visitor, eventually wooing it, engaged to it, learning to become a dutiful husband. My time writing with Ted Roethke also integrated me as an artist, because Ted’s support and his recognition of me as a poet caused another kind of adaptation inside me. It felt like I had entered or inherited a kind of wholeness of landscape consciousness that allowed me to experience every landscape as the structure of a poem in the making; and, of course, this changed my life forever.

it was Richard who shipped all of us young architects who worked for him back to Harvard to become landscape architects. We were the “northwest mystics” and a phenomenon around the GSD. Year after year, five years in a row Jerry Diethelm, Frank James, Grant Jones, Robert Hanna and Gary Okerlund were accepted. Jerry became the Landscape Architecture Chair at the University of Oregon; Frank became a famous and stalwart designer at Sasaki’s office; I, well you know what I did; Bob led urban design at the Boston Redevelopment Authority and then became professor of design for Ian McHarg at Penn and formed the office of Hanna Olin with Laurie; Gary became the most creative community planner in Charlottesville, Virginia. Before departing Richard Haag Associates, we had all come under the spell of Don Sakuma, one of Sasaki’s first designers in Watertown. He’d suggested that Don would be perfect to help Richard start the department of landscape architecture at the UW and he did.

Jones is survived by his wife, Chong-Hui, three children, Yon-Chong, Young-Kwon and Kaija, and four grandchildren, Hana, Yuna, Jason and Isabelle.