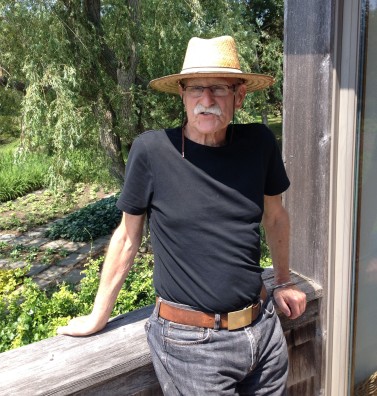

Remembering M. Paul Friedberg

By Charles A. Birnbaum

Maverick, innovator, fearless ... those just a few of the words that begin to characterize M. Paul Friedberg, the pioneering landscape architect who passed away on February 15, 2025, at age 93.

He was serious about the idea of child’s play and an unrepentant believer in the virtue of cities when U.S. cities were at their nadir. He worked mostly in the public realm, which meant that everyone was his client; he knew he was responsible both to them and for them. That challenge and joy of creating places for people, and the energy that people brought to public places, continually motivated Friedberg over a career that lasted more than six decades.

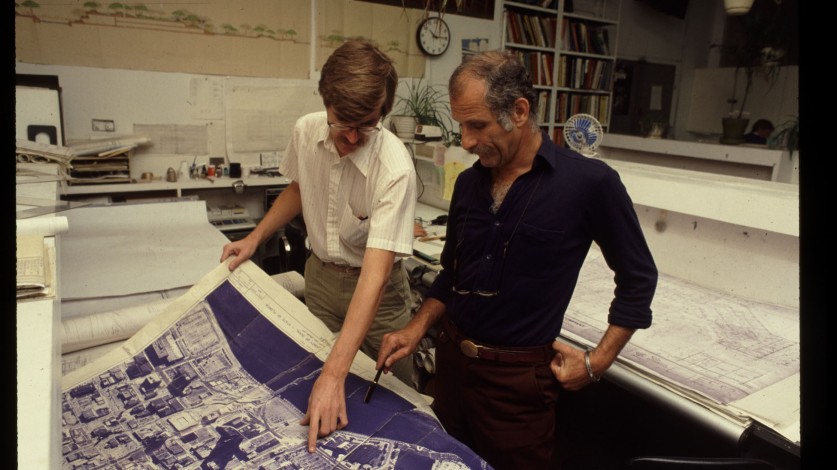

I first met Paul Friedberg in 1982 when I served as an intern in his New York City office. At that time Friedberg listed himself in the Manhattan Yellow Pages under “architects,” begrudgingly in acceptance of the fact that the public did not understand what “landscape architects” did or were.

Friedberg however would be an active and at times confrontational maverick on a quest to change that – as a landscape architect, architect, planner, artist, educator, author, urbanist, outdoor furniture-designer, and all around provocateur, Friedberg would push the envelope on what a landscape architect was (e.g. the lead planner – think big), what they did (e.g. reclaim the city), and what they looked like (e.g. actively courting and employing women and minorities in his practice and at the City College program).

In the footsteps of great landscape architects, including the Olmsteds (all three), and Gilmore Clarke and Michael Rapuano (enabled by Robert Moses), Friedberg came along when New York City and many others were in decline and many landscape architects had turned to the suburbs. Complaining that there was more than “drawing tennis courts and parking lots for engineers,” Friedberg recounted in a 2006 interview with The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) for a Pioneers Oral History that “I'm one of the few who accepted the city as a viable place to work, and to enjoy the diversity and the places that are created for people to come together, understand each other, through the joy of sharing. If there's anything, it's that. It's enjoying the city, removing the landscape architecture bias of the past the preconceived notion that the city is a hostile place. And, to me the city is where we are, the salvation. If you're going to preserve the larger landscape, the city is the only way. Density is the only way. That's it.”

It has been 60 years since Friedberg unveiled his radical solution for the problem of public housing in New York City – Jacob Riis Plaza (1965). This revolutionary approach, enabled by the Astor Foundation, launched Friedberg’s unique approach to what he called – the "total play environment" – a carefully choreographed series of simple, sculptural landscape vignettes that included a tree house, mounds, and a tunnel – all allowing for, and encouraging physical, emotional and sensory exercise and participation. Peter Walker, recipient of the 2004 American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) Medal (the same year that Friedberg received the ASLA Design Medal), has stated that “modern urban landscape design" began with Friedberg’s Jacob Riis Plaza, and “like Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion it was unlike anything seen before in the modern city.”

National and international accolades followed its opening (including in the New York Times and Life magazine). For the 34-year-old Friedberg this was a watershed event. In the more than half century that followed, with his work in the U.S., Canada, India, Israel, and Japan, Friedberg not only redefined the role and scope of the landscape architect but the design vocabulary employed, stylistic approach (embracing both Modernism and Postmodernism), and landscape typologies (blurring the lines between the landscape architect and the artist). His seminal works include the first “park plaza” with Peavey Plaza (1975), and the innovative Loring Greenway (1974), both in Minneapolis, MN; mixed use waterfront revitalizations (e.g. Battery Park City, 1988; The Yards, Washington, D.C., 2011); multi-use plazas (Pershing Park, Washington, D.C., 1981); rooftop plazas (Fordham University, N.Y.C., 1999), regional parks (Holon Park, Israel, 2000) and myriad civic spaces (Olympic Plaza, Calgary, Canada, 1987, Aroma Square, Tokyo, Japan, 2000).

In addition to those landscape architecture commissions where he challenged acceptable conventions, Friedberg’s constant pursuit of innovation and creativity in the making and crafting of children’s play spaces has been a constant in his career (e.g. Carver Houses in N.Y.C., 1963, East 67th Street Playground in Central Park, N.Y.C, 1985, and, Yerba Buena Gardens in San Francisco, 1998), as has been his quest to expand the profession as an educator.

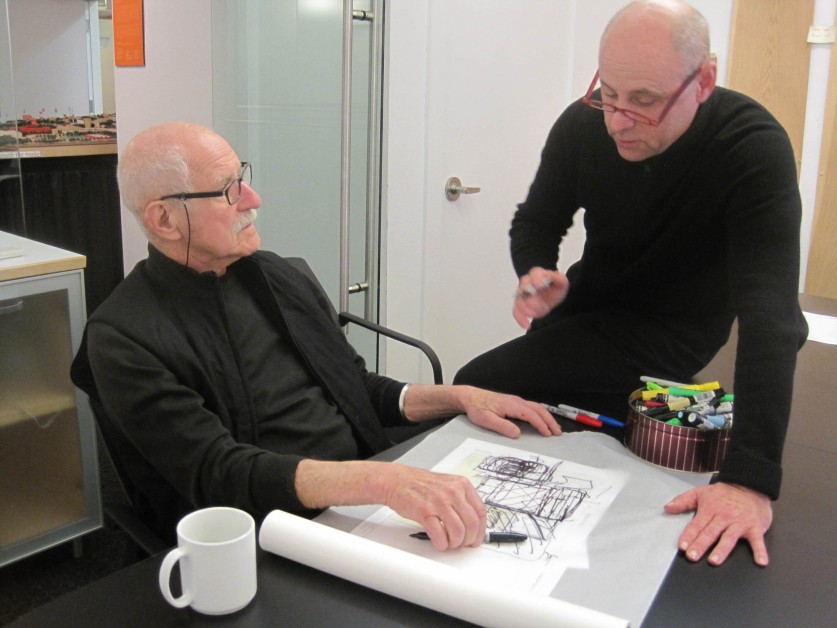

For the past few years Friedberg had been working on a book manuscript, which he asked me to review. In it he wrote: “Play is a state of mind and not only an act of physical activity. The scientist informs us that early childhood is a formative period in the child’s development. My view is that this behavior stays with us throughout our life and we should not treat it too flippantly. Play is something we never outgrow, nor should we.”

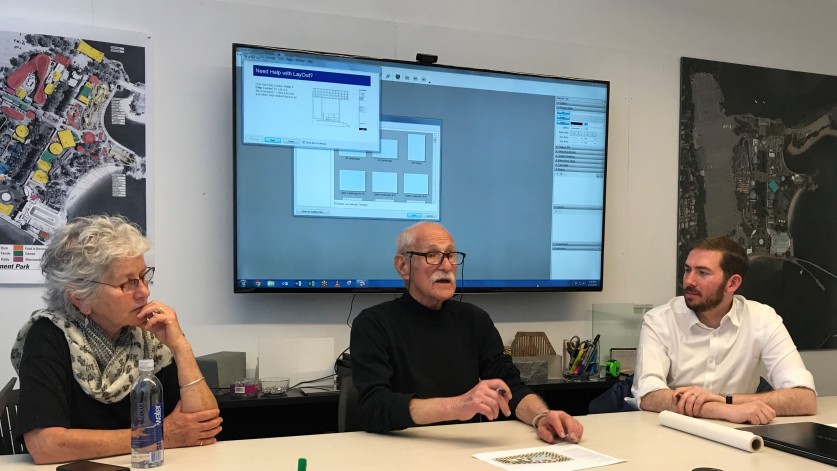

The fate of Friedberg’s three most significant works is mixed. His pioneering work, Jacob Riis Plaza, was destroyed in 2000 with no public discourse. Peavey Plaza was slated to be demolished and redesigned in 2011. Instead, it was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2013 and a lawsuit resulted in halting demolition; the work has more recently been successfully rehabilitated. Pershing Park was also on the chopping block, poised to be razed for a national World War One Memorial. That site was determined eligible for listing in the National Register in 2016, which helped to prevent its erasure. While the park’s central water feature was substantially altered and a 58-foot-long bronze frieze has replaced the original waterfall, the park’s organizational and visual structure has been protected as part of a larger rehabilitation campaign.

Friedberg discussed issues of change and continuity in landscape architecture in an insightful 2012 interview. Reflecting on the erasure of a number of his built works, in a 2014 essay for TCLF, Friedberg, who was not especially nostalgic about his built legacy, wrote: “In my own mind, I have tried to determine/justify reasons for preservation. After allowing for the obvious inherent educational value, and as a living museum reminding us of the past, the answer is simple: Is what replaces the existing work of landscape architecture of more value. Is the experience more elevating, does the design enhance the vision of oneself, community, and environment? Are we eradicating historic precedents?”

He added: “What I do desire is that when decisions to alter my work and the designs of others in the field be reviewed and sanctioned by knowledgeable people. That the decision to maintain, alter or demolish be supported by intelligent criteria and a jury of my peers—and at a minimum, for those landscapes that are significant that are razed, that they be documented.

“We, as professionals, contribute to the collective culture of the public realm. It is critical that what we do is valued, recognized and preserved until it is replaced by greater value. It is time to think ‘beyond Olmsted’ and properly value and protect contemporary works of landscape architecture.”

In addition to having served on the faculty at Harvard University, Columbia University, Pratt Institute, and other universities, Friedberg founded the Urban Landscape Architecture Program at the City College of New York in 1970 – the first such program in the country – and would serve as its departmental chair for the next 20 years. As Charlotte Frieze noted in a personal reflection that supplements the Pioneers Oral History that was produced and released by TCLF in 2009, “Paul created a program in which New York City was his classroom. He taught using real projects including the Brooklyn waterfront; Jamaica, Queens; and a 50-lot development in Bridgehampton. Our classroom extended to Central Park, The New York Botanical Garden and Woodlawn Cemetery.”

Friedberg’s unpublished book manuscript, which he continued to work on over the past year, opens with a parable of sorts:

“A man is on his hands and knees in a room. What is obvious is that the man is looking for something. When asked what he is doing, he replies that he is looking for a key that has been dropped. When asked where it was dropped, he replies, ‘over there’ and points to a dark part of the room -- not at all where he is looking. When asked why he is looking where he is and not where the key was dropped and most likely to be he replies, ‘but this is where the light is.’

“I see this as metaphor for the way we see our environment. We are satisfied to deal with where the light is. While the light and the key are not coincidental -- yet for some it is important to find out what the dark holds. The key or keys that are yet to be discovered. That is the signature of my work: the quest for what is lurking in the dark. This will prove more relevant.”

Friedberg discussed landscape architecture and the design of urban spaces in terms of theater, dance, and music:

“This is the age of the urban landscape -- one that the profession held out at arm’s length and resisted as long as possible.

“In my lifetime, distance has been re-calibrated, communication has shifted from the ear to the eye and is available to the illiterate. More people have been added to the decision process with less preparation. For instance, benches are not solely for convenience. Consider the bench as an orchestra seat in a play, a performance in which you have walk on parts. Except here, the players do not perceive themselves as a player. They’re animating the space for whatever their purpose is -- movement, strolling, hanging out. They are unscripted actors that are a critical component of the design.

“[T]he building is an object, and the landscape is space. The space serves dancers on a stage, employing the stage as a space for performance. Choreography is the creative way to interact with the space -- and each other in the space. The space is static until the dancer activates it.

“So, the urban landscape needs space to invite unscripted activities. Here, diversity is the essence of the interest. We become the dynamic that provides the constantly evolving interest. It’s here that minor dramas play out by those who are present -- waiting.

“In the play environment the distinction becomes clear. Kids will implore the viewers to ‘look at me’ and will become animated by how much interest they can garner. Our obligation is to set the stage.”

Let me conclude with another quote. In 2008, TCLF convened the conference, Second Wave of Modernism in Landscape Architecture at the Mies van der Rohe-designed Crown Hall on the IIT campus in Chicago. In the opening address Friedberg channeled his inner self-reflecting philosopher pragmatist: “Designing the landscape is an abstraction, as is the creation of music. Its function is a search for beauty. The musician achieves it by arranging sound. The landscape architect arranges space to be experienced by inhabiting it, not a bad way to start a day or spend a life.”

Paul Friedberg is survived by his wife, Dorit Shahar, and their daughter Maya, and by his sons Mark and Jeffrey from his marriage to his first wife, Esther, who passed away in 1982. He is also survived by an extraordinary body of work that continues to enliven cities, enrich those who interact with his landscapes, and to inspire landscape architects to create.