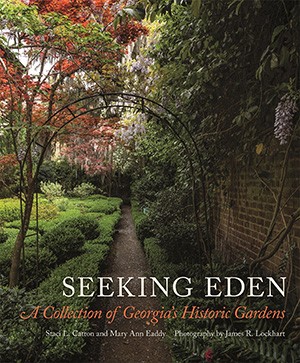

Seeking Eden: A Collection of Georgia’s Historic Gardens

Newly released from the University of Georgia Press, Seeking Eden: A Collection of Georgia’s Historic Gardens was authored by Staci L. Catron and Mary Ann Eaddy, with photographs by James R. Lockhart. In conjunction with the publication of the book, an exhibition (also titled Seeking Eden) is on view at the Atlanta History Center through December 31, 2018. The exhibition features photographs, postcards, landscape plans, and manuscripts, highlighting the importance of historic gardens in Georgia’s past, as well as their value and meaning within the state’s 21st-century communities.The following Q&A with the authors of the book explores several facets of Georgia’s rich garden heritage and their approach to writing about it.

What, in particular, differentiates Georgia’s garden heritage from that of other states and regions of the country?

Staci: Georgia’s garden heritage is closely linked to the state’s early history. As the last of the original thirteen colonies to be settled, Georgia’s colonial period essentially began with James Oglethorpe’s town plan for Savannah, started in 1733 and completed in the mid-nineteenth century. This seminal colonial town plan contained 24 wards with an open square at the center of each, surrounded by four trust blocks for public and religious buildings and four tithing blocks, each subdivided into ten residential building lots. This remarkable plan, which included public landscapes from its inception, was unique to Georgia and still holds valuable lessons to urban planners in the 21st century.

Oglethorpe and the new colonists also quickly established the Trustees’ Garden, a ten-acre experimental garden, to determine what kinds of plants might be grown commercially in Georgia. Although the primary purpose of the garden was scientific, it was also designed to be beautiful, its walks lined with orange trees and organized beds filled with fruit trees, herbs, and vegetables.

Mary Ann: In addition to its unique history, the state is large and geographically diverse, featuring landscapes from the coast to the mountains, as well as the area in between. So while the state’s garden heritage reflects national trends, it also illustrates important regional differences. Nationally recognized garden designers and landscape architects have examples of their work in Georgia, and a number of the gardens are associated with prominent individuals in the state’s and nation’s history.

The book revisits many of the gardens and landscapes first recorded in Garden History of Georgia, 1733-1933. How did you choose which sites to treat from the original text?

Mary Ann: There were over 160 gardens identified in Garden History of Georgia. The results of a Historic Landscape Initiative showed that about one third of these have been destroyed while one third still exist with only remnants of their original form remaining. The good news is that the final third not only exists but retain much of their historic design, with may of the gardens thriving. When selecting the gardens for Seeking Eden, we wanted landscapes that had a high degree of historic integrity as well as a visual appeal that could be highlighted through Jim Lockhart’s wonderful photography. Geographic distribution was also a consideration because we wanted to feature gardens from across the state.

Staci: All the designed landscapes featured in Seeking Eden are from Garden History of Georgia, 1733-1933. We included both publicly accessible and private gardens, selecting landscapes that represent various garden types and time periods. We also selected gardens based, of course, on the willingness of the property owner to participate in the process. There are still many significant historic landscapes in Georgia worthy of inclusion in a book, but space constraints did not allow us to select them all for Seeking Eden.

Does the book aim to underscore the stewardship of the landscapes in addition to documenting them, and, if so, how was that balance achieved?

Staci: Each chapter discusses the importance of and challenges with the stewardship of a particular site. For example, with the Swan House gardens, we highlighted how the Atlanta History Center has worked diligently to preserve this significant Country Place-era site, a masterpiece of the famed Atlanta architect Philip Trammel Shutze. Attention was brought to the walled boxwood garden at Swan House in 1995 when the Atlanta landscape architect Spencer Tunnell began a faithful restoration, completed the following year. This and other success stories are part of what the book documents. I should also add that proceeds from this publication are directed to the Garden Club of Georgia’s Historic Landscape Preservation Grants Program, which supports the preservation and restoration of historic properties across the state.

Mary Ann: Overall, we sought to place these landscapes within the context of their times and explore what had happened to them over the years. So many gardens have disappeared; why did these survive? In some cases, good fortune intervened. In others, concerted efforts by their owners ensured their long-term preservation. We tried to explore this throughout the book. We also wanted to give readers an idea of how the gardens looked in 1933 (when Garden History of Georgia, 1733-1933 was published) versus 2017. We were fortunate that the earlier book contained photographs and various plans and drawings. In several of our chapters, we were able to place a 1933 image next to one of Jim’s current photographs of the same location to indicate how the garden had or had not changed.

Speaking of change, how did the Civil War transform Georgia’s garden culture?

Staci: During the Civil War, Georgia became a battleground that saw physical devastation of the landscape and the collapse of the structure of plantation society, which was based on cotton culture and slavery. From 1866 until the close of the century, many large plantations were divided into smaller farms, and agriculture shifted to tenant farming and the sharecropping system. Significant changes to the landscape followed, as exploitation of the state’s natural resources led to lumbering, mining, quarrying, and turpentine production. Many cities and towns in Georgia recovered economically in the decades after the Civil War, while the countryside continued to languish.

Mary Ann: It is also true that, in the aftermath of the Civil War, the focus, by necessity, was on surviving and rebuilding; therefore, the development and care of formal, ornamental gardens was not a priority. In addition, with the emancipation of a large population of formerly enslaved African Americans, a major shift occurred in the labor force. When people began to think of pleasure gardening again, intricate, labor-intensive landscapes proved too difficult to maintain except by the extremely wealthy.

Given, as you mention, the relationship between slavery and the landscapes themselves, how did you decide how and when to interweave that narrative into the text?

Mary Ann: The labor force used to maintain the antebellum gardens featured in the book primarily comprised enslaved African Americans, but little is written about their role in developing and maintaining these landscapes—something that became apparent as we conducted our research. We do know, or have reason to believe, that many of these landscapes were prepared and tended by African Americans, and this is another aspect of the gardens’ histories that deserves recognition.

Staci: We tried to interlace historical events and conditions as a part of the story of each designed garden. But I wholeheartedly agree that it is very clear that much more research and writing needs to be done on the roles of enslaved people in the story of antebellum gardens in Georgia, as well as the roles of African Americans in the design and care of gardens developed during the Jim Crow era.

The book documents the contributions and leadership of a number of women who created and maintained many of the gardens. Was that a specific goal from the outset?

Mary Ann: Before beginning the book, I had a general sense of the importance that women played in the development and care of many of these gardens, and I definitely wanted to acknowledge this. I did not, however, go into the project with the idea of specifically emphasizing that role. I wanted each garden’s story to unfold naturally and the research to lead me to the most significant aspects of their histories.

Staci: Having already researched the topic, it was my specific goal from the outset to document the contributions and leadership of some women who created and maintained many of the designed gardens in Georgia.

Do you think that women’s roles in these areas reflected the lack of other avenues for their professional development in the past?

Staci: Victorian norms continued to relegate many women to the domestic sphere, whether in their own homes or working for other women in theirs in the late nineteenth century. Nationally, the 1890s saw the dawn of the Progressive Era, with women from all classes, races, and backgrounds entering into public life, expanding their roles in society, and becoming increasingly politicized. Options for Georgia women—both black and white—grew, particularly in education, reform, and employment. While it is true that working in garden design and/or gardening as a profession was viewed as a “suitable” field for women during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, women featured in Seeking Eden certainly had a passion for gardening and horticulture.

Mary Ann: I would agree. For many of these women, ornamental gardening appeared to be a genuine passion, a tangible expression of their love of beauty. Although a certain social status often necessitated having a formal garden, the attention and care given to many of these spaces seemed to reflect a genuine love for the landscape. Take, for example, Martha Berry, whose life work was the creation of Berry College on the outskirts of Rome, Georgia. She was intensely involved with decisions related to the campus landscapes, including such details as selecting plants and moving trees. Yet she managed to establish and direct a series of private schools founded on the tenets of academic achievement, hard work, and religious faith. Although she had a professional career, she found time to ensure that beauty, in the form of gardens, was a part of her life and work.

What was the biggest challenge in completing this project?

Staci: For me, the main challenge was balancing the site visits, research, and writing with other work and personal obligations. Fortunately, my co-author, Mary Ann, the book’s photographer, Jim Lockhart, and I made a great team.

Mary Ann: My biggest challenge was intensely personal and totally unanticipated. In October 2016, before our manuscript was due to the University of Georgia Press in January, I became ill. While I was able to continue writing, progress was incredibly slow. Thanks to Staci’s extraordinary efforts, we were able to meet our deadline. Both Staci and Jim were extremely supportive during my recovery, which occurred during the editing phase of the process.

What is your favorite landscape treated in the book, and why?

Mary Ann: I find the story of Dunaway Gardens especially compelling. This rock and floral garden was the dream of the actress Hetty Jane Dunaway Sewell, who developed this landscape in the 1920s and early years of the Depression as the backdrop for a theatrical center. Dunaway was a popular tourist destination until the mid-twentieth century, but after years of neglect it nearly disappeared. The perseverance and vision of another woman, Jennifer Rae Bigham, brought this remarkable landscape back to life.

Staci: I continue to be intrigued with Millpond Plantation in Thomasville, Georgia. A winter retreat and hunting plantation with a lavish home and elaborate ornamental gardens, Millpond was created between 1903 and 1910 by the Cleveland businessman Jeptha Homer Wade II. It is an extraordinary example of a Country Place-era estate developed in the Red Hills region of Georgia by the renowned landscape architect Warren H. Manning. It is also significant for its vital role in the conservation of old-growth longleaf pine forests. During my research for this chapter, I became enthralled by Manning’s work, particularly as he evaluated his design and planning projects from an environmental viewpoint, conceptualizing projects as parts of larger regional systems. Moreover, Jim Lockhart’s photographs throughout the book are vital to telling the story of each garden, and some of my favorite images that he captured are of Millpond.

Staci L. Catron (pictured, far right) serves as the Director of the Cherokee Garden Library, a Library of the Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. She curates numerous exhibitions at the Atlanta History Center, lectures regularly regarding rare garden books and historic landscapes, and is published in many newsletters, journals, and books.

Mary Ann Eaddy has worked in the fields of historic preservation and history throughout her professional career. A former manager in the Historic Preservation Division of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, she has experience both in Georgia and South Carolina’s State Historic Preservation Offices, as well as in the National Park Service.

James R. Lockhart has been photographing architectural history for 40 years. As a photographer for the State of Georgia, Historic Preservation Division, he documented over 1,600 nominations to the National Register of Historic Places. He is the recipient of an Honor Award from AIA Georgia for contributions to the architectural profession and to historic preservation, and an Award for Preservation Excellence from the Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation.