Located north of San Francisco near Muir Woods National Monument, this wooded hillside tract was the longtime home of poet and groundbreaking lesbian feminist Elsa Gidlow. The site was named Druid Heights by Gidlow and would be a haven of tolerance, social reform, and creative expression throughout her 30-year tenure there. Now managed by the National Park Service, the once-vibrant community is largely vacant, the empty structures suffering from years of neglect. Without attention and maintenance, this LGBTQ landmark and incubator of important cultural and social movements will be lost to the forces of nature, and its place in American history risks being erased.

History

Born in Hull, Yorkshire, England in 1898, Elsa Gidlow spent most of her childhood in Quebec, Canada, after immigrating there with her family. In 1920 she moved to New York City and began supporting herself by writing for the progressive magazine Pearson’s. Gidlow’s time in New York was highlighted by the publishing of her first poetry book On a Grey Thread, considered the first American volume of openly lesbian love poetry. She continued writing throughout the rest of her life, supporting herself as a freelance journalist and publishing several more books, including her autobiography Elsa, I Come with my Songs, released only weeks before her death in 1986. She was an active participant in many progressive causes and is recognized as a foremother of the lesbian feminist movement.

Druid Heights, CA, photo by Tom Fox, 2018.

Druid Heights, CA, photo by Tom Fox, 2018.

Gidlow moved to San Francisco in 1926 and eventually purchased a cottage in the vacation suburb of Fairfax. A confident and courageous forerunner of LGBTQ expression, she once stated "I was, and am, first a human person, then a woman, then a woman whose primary identification and loyalty is with women as lovers and friends.” Despite her assurance, the poet became a target for discrimination based on her seemingly radical views, independence, and sexual orientation. After becoming a member of her neighborhood’s planning commission, she was accused by her political opponents of being a Communist sympathizer in 1947, stripped of her position, and brought before the California State Senate’s Committee on Un-American Activities. The persecution she faced, along with the rapid postwar changes to her neighborhood, motivated her to find a quieter community of open-minded people with compatible interests.

In 1954 Gidlow was introduced to a five-acre property north of San Francisco in the hills of Marin County by an acquaintance, builder and musicianRoger Somers. The site, a former ranch homestead with several vernacular structures, was situated at the edge of the primeval forests of Muir Woods National Monument (the first such monument to be created from land donated by an individual) below Mount Tamalpais. The property is accessed by a one-lane, unpaved road that winds through the hills for more than a mile. Grassland and groves of coast live oak and bay laurel cover ground that slopes down to the Redwood Creek to the south and west. Swaths of eucalyptus and Monterey cypress, planted as a windbreak, ring the site. Seeing the opportunity to create the community she dreamed of finding, Gidlow purchased the land and named it Druid Heights.

Together Gidlow and Somers fashioned the property into a bohemian creative retreat. An imaginative and exuberant craftsman, Somers built one-of-a-kind, improvised structures that intermingled with the landscape and the existing vernacular buildings of the former ranch. Notable projects include the transformation of a 1920s farmhouse into the “Twin Peaks” house, which still stands today and features a Polynesian-inspired saddle-backed roof, patterned roof shingles, custom furnishings and cabinetry, and Japanese-style rooms. Several other structures remain on the property, including a circular study and library fashioned from redwood timbers, the “Mandala House,” influenced by the late works of Frank Lloyd Wright, and the “Moon Temple,” a small meditation hut near Gidlow’s home, with stained-glass windows and organically edged shingles. In addition to her writing, Gidlow worked to improve the landscape by clearing underbrush, planting ornamentals, building terraced garden beds, and cultivating organic flower and vegetable gardens. She would live there for the rest of her life.

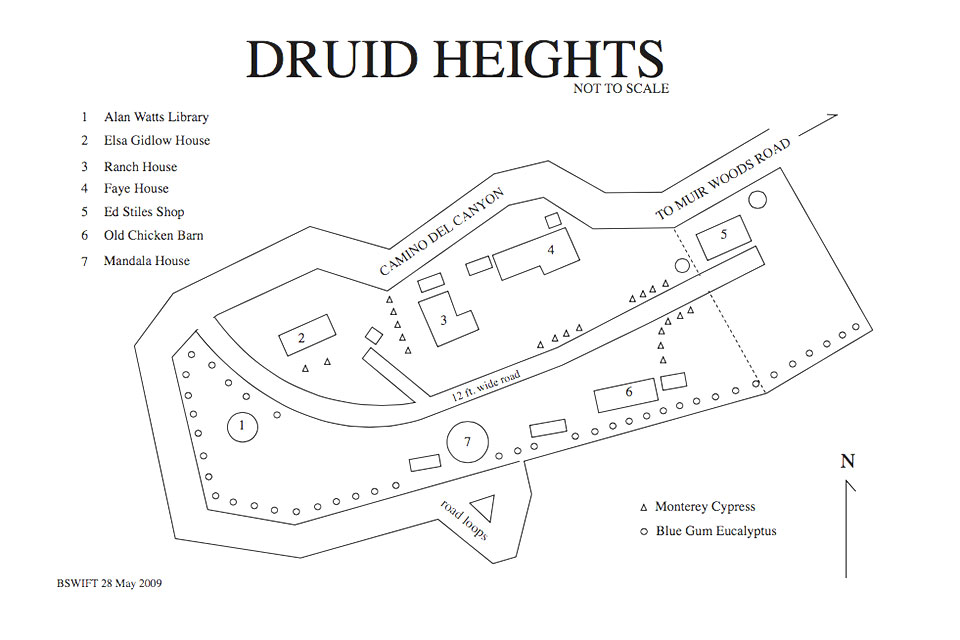

Map of Druid Heights, courtesy Michael Toivonen.

Map of Druid Heights, courtesy Michael Toivonen.

Writing about Druid Heights in her autobiography, Gidlow expressed her desire “to give courage to others with urges to free themselves for deeper fulfillment than the ossified patterns of establishment culture permits.” Gidlow and Somers attracted many writers, artists, musicians, and friends to their bohemian enclave, where they felt free to be themselves. Notable residents were poet Gary Snyder, philosopher Alan Watts, sex-positive activist Margo St. James, and feminist law professor Catharine A. McKinnon. The long list of well-known visitors included jazz musician Dizzy Gillespie, actress and comedian Lily Tomlin, poet Allen Ginsberg, and choreographer Anna Halprin, all drawn to the vibrant retreat by its residents’ alternative and tolerant lifestyle, beautiful scenery, and charismatic architecture. The landscape and built environment of Druid Heights affords a unique look into the social and aesthetic values of social movements spanning more than three decades, including the Beat Generation immediately following World War II, the hippie subculture of the 1960s, and the feminist movement of the 1970s.

Threat

In 1972 the National Park Service added approximately 50 acres to the Muir Woods National Monument via legislative action and began purchasing tracts to be used for maintenance and resource protection of the greater Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Despite initial resistance from Gidlow, who hoped that the property would remain a retreat for female writers and artists, the NPS purchased the three parcels comprising the Druid Heights property in 1977. At the time of the sale, the land owners were allowed to purchase lifetime leases. The community lost its foundational member and primary advocate in Gidlow, who died after suffering multiple strokes in 1986; its other forefather, Somers, passed away in 2001.

The once-thriving enclave relied on its residents to collectively undertake maintenance and repairs. Now, with many of the buildings uninhabited, threats to their continued existence are imminent. In the future, the NPS will be the sole caretakers of the property, but there is every indication that the deterioration of Druid Heights from falling trees, trespassers, overgrowth, water, pests, and insect damage will likely continue unchecked. A study and determination of Druid Heights’ eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) were nearly completed in 2011, but the 146-page draft document was subsequently set aside. The site was featured in an article in the New York Times in 2012; yet plans to include Druid Heights in the NRHP did not move forward.

Presently, the National Park Service’s General Management Plan for the Muir Woods National Monument states that the access road to Druid Heights is to be “converted into a trail accessible by foot or light service vehicle. Some historic structures associated with the bohemian community at Druid Heights would be preserved to the extent practicable and consistent with limited access.” Questions about this plan remain, particularly how the buildings might be maintained without an access road for regular service vehicles or emergency vehicles in the case of a fire.

The remoteness and privacy of Druid Heights was cherished by its residents and enabled them to express themselves freely without fear of prejudice. Author Erik Davis describes the enclave as “one of those rare places that is known but not known.” Now, the site’s anonymity is one of the chief factors working against its survival. As Davis told the New York Times in 2012, “there aren’t a lot of places where you can memorialize this countercultural moment.” Druid Heights is a rare exception, a place that documents and memorializes the ideas of an important cultural awakening and celebrates the life of Elsa Gidlow. And despite the dilapidated state of many of its structures, the site retains its integrity as a cultural landscape, with the layout and setting of the community still very much intact.

What You Can Do to Help

It is important to stress that, because of the fragility of the structures, and out of respect for the privacy of the handful of residents who remain there, now is not the time to visit Druid Heights—the site is, in fact, closed to the public until further notice from the National Park Service. But those interested in the history and stewardship of the site should follow and support the work of Save Druid Heights, a recently formed group that is dedicated to preserving the cultural legacy and cultural landscape that Gidlow and others left for future generations. Through its outreach, social media, and networking, the group is working with TCLF and other stakeholders to raise awareness about this unique cultural asset.