Introduction

Introduction

Inspired by our nation’s motto, e pluribus unum, “out of many, one,” Landslide 2018: Grounds for Democracy highlights threatened cultural landscapes throughout the nation that are key to remembering, contextualizing, and interpreting the struggles for civil and human rights in the United States. In keeping with TCLF’s prior annual thematic reports about at-risk landscapes, the sites were nominated by individuals or groups advocating for their stewardship.

The choice of this year’s theme was perhaps prescient. A half century has now passed since 1968, when marches, riots, and even assassinations seemed to signal that the fabric of the American democracy was unraveling. That explosive year was in many ways the flashpoint of struggles by generations of Americans to secure the personal liberty and equality promised but not yet delivered by their citizenship. Although the ensuing decades have undeniably brought progress on many fronts, the present moment, too, is rife with upheaval and social division—a sign of how far we have yet to go on our journey toward “a more perfect union,” despite how far we have come.

As places that have been “affected, influenced, or shaped by human involvement,” cultural landscapes can anchor the collective memories of our national failures and triumphs, reminding us of the lessons from a past in which the basic rights we now take for granted were publicly tested and contested. Many of these landscapes and the stories they tell now face threats to their legibility or outright survival.

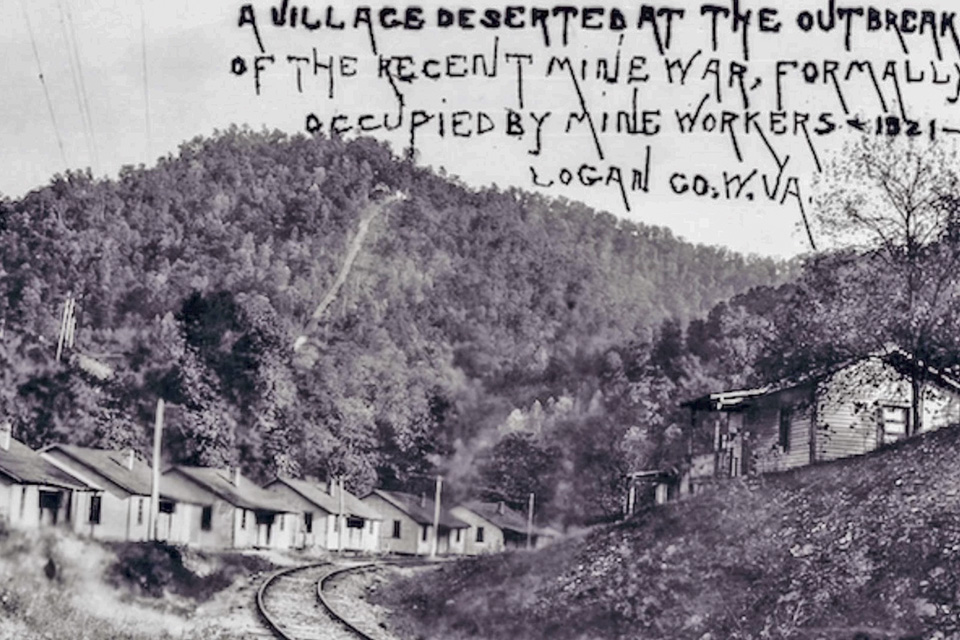

A village near Logan, WV, stands deserted at the outbreak of the Mine Wars, 1921, photo courtesy West Virginia Mine Wars Museum.

A village near Logan, WV, stands deserted at the outbreak of the Mine Wars, 1921, photo courtesy West Virginia Mine Wars Museum.

The Battle of Blair Mountain was the largest armed uprising in American history since the Civil War, pitting some 10,000 coal miners against a system in which privately paid guards maintained order in “company towns” without elected officials or independent law enforcement. The Blair Mountain Battlefield in Logan County, West Virginia, is where miners fought for basic workers’ rights in 1921, including safe working conditions, a living wage, and even the right to congregate freely. The site is an archaeological treasure trove that has never been fully explored, and the secrets it holds could be wiped away by timbering and drilling.

Located on Georgia’s Sapelo Island, the community of Hog Hammock is one of the last surviving remnants of Gullah-Geechee culture, tracing its roots to enslaved West Africans brought to the island’s plantations in the 1700s to labor in captivity. During the period of Reconstruction, the freed slaves took collective ownership of the land they had formerly worked in bondage, creating a thriving and enduring agrarian community that represented an alternative African American experience in the postwar South. But after decades of sharply increasing tax assessments in the wake of new development, the fewer than 30 remaining permanent residents of this small enclave are struggling to keep their culture and community intact, even as the vernacular landscapes that support their way of life are disappearing.

Princeville, North Carolina, was the first town in the United States incorporated by African Americans. Established by freed slaves on the spot where a Union soldier read aloud the Emancipation Proclamation, the town inhabits a low-lying, flood-prone plane beside the Tar River, the only land made available for sale to former slaves. After generations of building and rebuilding, a marked increase in flooding in recent decades may prove an insurmountable threat to the naturally susceptible landscape—and the rich history it embodies.

Flooding at Princeville after Hurricane Floyd in 1999, photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Flooding at Princeville after Hurricane Floyd in 1999, photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

On a small and unassuming plot of land in rural Battenville, New York, sits a house on the verge of collapse, a two-lane highway passing uncomfortably close to its front door. An easy-to-miss placard suspended from a post in the yard is the only indication that this derelict property is the Susan B. Anthony Childhood Home, where, between 1832 and 1839, the future champion of women’s rights would first form her rebellious ideas about gender and racial equality. This significant piece of our nation’s history is also the lynchpin of a potential historic district integral to Susan B. Anthony’s story. Sadly, this site may soon be erased by long-term and continuing neglect.

The open lynching of African Americans during the Jim Crow era is perhaps the most gruesome chapter in the nation’s history, when crowds gathered in public to witness the cruel spectacle of torture and death dispensed with impunity. Supported by new documentary efforts, work is now underway to commemorate several lynching sites in Shelby County, Tennessee. These landscapes of racial terror and control are most often “invisible,” unmarked, nondescript places whose obscurity is complicit in concealing the inhumanity they represent. Only when these sites are acknowledged and memorialized will the deep and festering wounds that they evoke begin to heal.

The lynching of Lige Daniels in Center, TX, August 3, 1920, photo courtesy Equal Justice Initiative.

The lynching of Lige Daniels in Center, TX, August 3, 1920, photo courtesy Equal Justice Initiative.

For African Americans, the effects of racial segregation were felt even in death. Established in the early 1920s in the Brownsville neighborhood of Miami, Florida, Lincoln Memorial Park is one of the oldest African American cemeteries in Dade County. It is the final resting place of many soldiers who served their country, from the Civil War to Vietnam, as well as local luminaries and pioneers who shaped the history and culture of the region. But like innumerable African American cemeteries across the nation, Lincoln Memorial Park became an overgrown ruin of litter and desecrated graves. Now the local community is rallying to restore this historic landscape to its former glory.

After President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order No. 9066 on February 19, 1942, the U.S. Army forcibly removed the entire population of people of Japanese descent from the West Coast, confining them in perpetually guarded camps established in remote areas of California, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, and Arkansas. It is estimated that more than 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, two-thirds of them U.S. citizens, were rounded up and confined in the camps, many for the duration of World War II. Although funds have been allocated by Congress to preserve and interpret the history of the Japanese American Confinement Sites, an annual challenge to secure the already appropriated funds has been an unfortunate pattern in recent years.

Detainees working in the surrounding filds, Tule Lake War Relocation Center, CA, 1942, photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Detainees working in the surrounding filds, Tule Lake War Relocation Center, CA, 1942, photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Known affectionately as “Muny,” Lions Municipal Golf Course was built just two miles west of the State Capitol in Austin, Texas. Aside from its historic design, Muny is best known as the first desegregated municipal golf course in the South, thanks to the rebellious act of a young African American caddie in 1950. The University of Texas, Austin, which owns the land that Muny occupies and leases it to the City of Austin, decided in 2011 that it will not renew the lease beyond 2019, opting instead to destroy Muny to make way for a mixed-use development.

North of San Francisco, near Muir Woods National Monument, is the wooded hillside tract that was the longtime home of poet and groundbreaking lesbian feminist Elsa Gidlow. Named Druid Heights by Gidlow, the site served as a haven of tolerance, social reform, and creative expression throughout her 30-year tenure, even as her loyalty to her country was publicly questioned. Now managed by the National Park Service, the once-vibrant bohemian enclave is largely vacant, its structures suffering from years of neglect. Without maintenance or, at least,e the comprehensive documentation of its historic landscape, this LGBTQ landmark and incubator of important cultural and social movements will soon disappear.

The Ranch house at Druid Heights, CA, photo by Tom Fox, 2018.

The Ranch house at Druid Heights, CA, photo by Tom Fox, 2018.

And finally, located on the nationally landmarked Bronx Community College campus in New York City, the Hall of Fame for Great Americans is at once the birthplace of fame as an American democratic ideal and the backdrop for mid-century activism by persons of color. Designed by Stanford White of the renowned firm McKim, Mead & White, the Hall contains busts of great Americans, nationally nominated and then elected for inclusion, and was once a much visited site that garnered national media attention. As current debates about who and what should be the subject of public commemoration intensify, the Hall stands as a monument to another ideal: that there is one common, American, concept of greatness. But it is in dire need of repairs if it is to survive to inspire a more inclusive image of that ideal.

These and many other threatened cultural landscapes not only bear physical witness to events and individuals of historical significance, they are an integral part of the cultural life of the nation, reminding us of who we are, how we became so, and the lessons we can’t afford to forget.