Located on the nationally landmarked campus of Bronx Community College (BCC), City University of New York (CUNY), the Hall of Fame for Great Americans is at once the birthplace of fame as an American democratic ideal and the backdrop for mid-century activism by persons of color. Containing busts of great Americans, nationally nominated and then elected for inclusion, the Hall was once a much-visited landmark that garnered national media attention. As current debate intensifies regarding who and what should be the subject of public commemoration, the Hall of Fame stands as a monument to another ideal: that there is one common, American concept of greatness. But the Hall is in dire need of repairs if it is to survive to inspire a more inclusive image of that ideal.

History

The Bronx's University Heights neighborghood grew up around the campus, built by New York University (NYU) as its uptown location at the dawn of the twentieth century. In designing this Beaux-Arts campus, architect Stanford White of the renowned firm of McKim, Mead & White masterfully took full advantage of the 45-acre site on a bluff overlooking the Harlem River. A preliminary landscape plan by Calvert Vaux in 1894 was likely unimplemented; a series of plans and correspondences from 1912 to 1923 indicates the possible involvement of Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and the Olmsted Brothers firm. Although White’s master plan was never fully realized, the core of his design still reads clearly in the Gould Memorial Library, which serves as the centerpiece rotunda, and in the buildings that flank it, the Hall of Language and the Hall of Philosophy.

Also designed by White in 1900, the Hall of Fame encircles the rear façade of Gould Memorial Library, covering its exposed concrete retaining walls while linking to the flanking buildings on either side. With its eclectic Roman style, monumental scale, and commanding position on the Bronx’s highest natural point, the 630-foot-long, ten-foot-wide, open-air colonnade is visible on both sides of the Harlem River and offers sweeping, panoramic views that extend across upper Manhattan to the steep cliffs of New Jersey’s Palisades.

Gould Memorial Library, 1904, photo courtesy Detroit Publishing Company.

Gould Memorial Library, 1904, photo courtesy Detroit Publishing Company.

The Hall of Fame was envisioned as “America’s Pantheon,” a permanent exhibition of busts of great Americans whose achievements spanned many fields of endeavor: authors, educators, architects, inventors, military leaders, judges, theologians, philanthropists, humanitarians, scientists, statesmen, artists, musicians, actors, and explorers. This variety was unprecedented at a time when only political or military leaders were afforded public commemoration. Below each bust is a bronze tablet designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany, containing the name, birth date, and death date of the commemorated individual, along with a memorable quote from them. Among the master sculptors whose work is represented are Daniel Chester French, sculptor of the Lincoln Memorial; James Earl Fraser, whose work includes the figures of “Justice” and “Law” for the U.S. Supreme Court; and Frederick MacMonnies, whose reliefs grace Fifth Avenue’s Washington Arch. The President of the National Sculpture Society once declared this to be “the largest and finest collection of bronze busts anywhere in our country.”

The Hall now contains 96 busts of various individuals, dead for at least 25 years, who were nominated over seven decades via a grassroots, democratic process. The elections and installations were closely followed by the media and broadcast live on major networks. Private citizens from across the nation rallied support and raised money through letter-writing, fundraising events, and bake sales to secure their nominees’ election. Nominees were selected according to a system modeled on the Electoral College, including a Board of Electors comprising men and women who had in their own right achieved a degree of renown. Six Electors were later inducted into the Hall of Fame themselves, including Alexander Graham Bell, Woodrow Wilson, and Grover Cleveland.

Among those persons elected to the Hall are several of America’s Founding Fathers, as well as social activists such as Jane Addams, the founder of Hull House who became the first American woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize; Susan B. Anthony, an abolitionist and activist whose work ultimately gave women the right to vote; and Justice Louis Dembitz Brandeis, the first Jew to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Sudents visit the Hall of Fame in 1958, photo courtesy Bronx Community College.

Sudents visit the Hall of Fame in 1958, photo courtesy Bronx Community College.

Shifting Demographics, and Who Gets to Choose Great Americans?

Facing severe financial difficulties, NYU sold the campus in 1973, enabling BCC to inherit this architectural masterpiece. BCC and NYU split the cost of running the Hall from 1973 to 1976, when the last election was held. Thereafter, BCC became solely responsible for the Hall of Fame, which was listed in the National Register of Historic places in 1979.

As historian and BCC faculty member Prithi Kanakamedala, Ph.D. notes, at the time of its move to NYU’s former campus, BCC boasted the highest number of African American and Hispanic students in the CUNY system—about 40 percent. In Nursing, one of BCC’s most successful academic programs, 50 percent were students of color. This demographic shift alarmed many, including legendary urban planner Robert Moses, who warned the Hall’s Electors that the transition from NYU’s ownership to BCC’s meant that “factors other than the merit of individuals as judged by the electors” would determine who was named to the Hall. Moses’ fears were echoed by alarmed Electors, who proposed moving the busts to the Smithsonian Institution or the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the end, CUNY prevailed and the busts remained, but BCC never selected its own Great American.

NYU’s disinvestment was part of a broader movement of resources away from the Bronx in the 1970s that resulted in a period of arson, white flight, abandoned buildings, and urban blight. And yet this era also heralded a new chapter of achievement, activism, art, poetry, and protest from the low-income people and people of color who settled and stayed. Their accomplishments, while not commemorated in the Hall of Fame, intersect and enhance the American story at several significant points and contribute to the rich and nearly forgotten history of the University Heights campus.

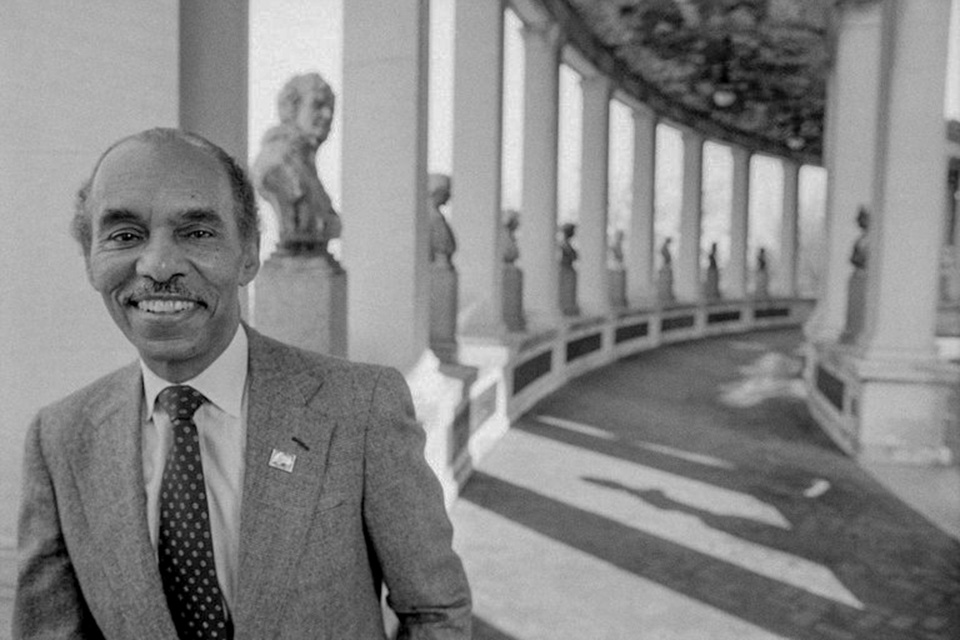

Roscoe Brown in the Hall of Fame in 1958, photo courtesy Bronx Community College.

Roscoe Brown in the Hall of Fame in 1958, photo courtesy Bronx Community College.

More Great Americans

When BCC selected Dr. James A. Colston as its second president in 1966, both made history: He was the first African American to be named a college president in New York State. Dr. Colston oversaw BCC’s move onto the University Heights campus and an explosion of enrollment, which doubled to nearly 14,000 students. Students were engaged and politically active, once shutting down the school to demand greater diversity in hiring. Those efforts led to the first courses on African American and Latino history at BCC.

The twenty-year-old Joan Bird, a former BCC nursing student, was among the infamous Panther 21, arrested in 1969 and charged with participating in a Black Panther conspiracy to bomb commercial and municipal sites. In 1971, after the longest political trial in New York City history, all 21 defendants were fully acquitted. The jury found that the police used excessive means to disrupt Panther community programs and unethical interrogation tactics to get members to “confess” to crimes. Among Ms. Bird’s co-defendants was Afeni Shakur, who was pregnant with son Tupac Shakur at the time of the trial.

Although democratic, the Hall of Fame has long been criticized for not being representative. Only eleven women have been elected to the Hall (just ten were installed), and only two African Americans were elected, both of whom had ties to the Tuskegee Institute: founder and educator Booker T. Washington and inventor George Washington Carver.

BCC’s third (and second African American) president, Dr. Roscoe C. Brown, Jr., thought the Hall of Fame did not reflect the campus and created his own way of honoring Great Americans by inaugurating the BCC Humanitarian Award. During his tenure, BCC hosted author James Baldwin, artist Romare Bearden, dancer Pearl Primus, musician and “King of Latin Music” Tito Puente, playwright Douglas Turner Ward, and activists including Angela Davis, Ossie Davis, Paul Robeson Jr., Andrew Young, and Harry Belafonte, among others.

Threat

In the decades after it opened, the Hall of Fame drew as many as 50,000 visitors annually. As Michael T. Kaufman wrote in The New York Times, “For 60 years it was taken seriously, drawing tourists like an urban Mount Rushmore and generating national news coverage and debate for its elections.” But along with other landmarked buildings on the University Heights Campus, it is now in dire need of repairs to counter decades of physical deterioration. Water damage, pollutants, and the effects of weathering have opened joints, cracked both ceiling tiles and brick pavers, and deteriorated limestone cornices. Many statues have deep stains from biological contaminants, and run-off from copper elements in the roof has discolored the Tiffany tablets, making many unreadable. The historic steps and gate to the Hall of Fame from Sedgwick Avenue and Hall of Fame Terrace are inoperable, as is a fountain at the base of the Hall of Fame. The stepped retaining wall, with stone finials that uphold of the historic walk and steps, is a character-defining feature of the historic designed landscape and is also in poor condition.

The cost to repair the Hall—an estimated $12 million—is more than BCC can afford. The most urgent of these repairs will require $1.2 million. A recent evaluation of the campus also indicated a significant need for landscape preservation to recapture the historic setting and landscape character of the complex of buildings designed by Stanford White.

Although an Advisory Board of architects, preservationists, and others has been formed to save the Hall of Fame, their efforts have been hindered by a second major threat: obscurity. Ironically, for a site that was virtually the birthplace of fame in America, the facility has been largely forgotten. As James Panero, editor of The New Criterion, wrote of the Hall of Fame in 2017: “A relic of urban history, it is rather one of the city’s most remarkable memorials to Beaux-Arts design and turn-of-the-century aspiration, the shadow of one university and the responsibility of another, now nearly unknown beyond the students and faculty who keep it alive.”

What You Can Do to Help

Donate to the BCC Foundation to restore the Hall of Fame. Established in 1985 as a 501(c)(3), the BCC Foundation raises funds to support BCC in several endeavors, including maintaining the Hall of Fame.

Visit the Hall of Fame. The College gives regular tours and encourages group visits such as the recent on-campus gathering of the American Institute of Architects. Follow these and other events on Twitter.

Share your stories, documents, and artifacts relating to the Hall of Fame or any of its elected Great Americans. BCC Archives is seeking to expand its collection of photos, letters, documents, artifacts, and audio-visual materials that detail the process of nomination and selection to the Hall of Fame. Across the country, clubs, affinity groups, scholars and others lobbied for the election of persons of achievement, and BCC Archives is eager to preserve these materials for scholarly and historical uses.