Sprout of Gotham

Authored by: Thomas J. Campanella

Egos cast long shadows, especially those of powerful men. The skilled professionals who worked alongside Robert Moses knew this all too well, which is why the names Gilmore D. Clarke and Michael Rapuano—among the most influential landscape architects of the twentieth century—ring few bells these days. Their many public landscapes in New York City—the Henry Hudson Parkway, Riverside Park; Bryant, Jacob Riis and Orchard Beach parks; site plans for two worlds fairs, the U.N. Headquarters, Idlewild Airport and 60 public housing projects—are almost always credited to Moses alone.

Lost in umbra of these men was a woman who helped forge many of these places, whose quiet mastery of flora brought beauty and verdure to the city. Her name foretold her calling. Mary Elizabeth Sprout was born in 1907 to a middle-class family in Montrose, Pennsylvania. She spent most of her youth in nearby Binghamton, developing a keen interest in horticulture. Named "Class Prophetess" in high school, Sprout studied at the Cambridge School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture and earned a B.A. from Smith College in 1928.

She moved to New York that fall for a job with Annette Hoyt Flanders, reporting in the Smith Alumnae Quarterly that her work was "very interesting, consisting mostly of going out to large estates and directing the planting of gardens."1 Initially a "draftsman," Sprout was soon managing the office, tagging plant material and supervising site construction. She prepared plans for the Charles E. Van Vleck, Jr.'s "Ballyshear" estate in Southampton, New York; "Morven," the Charles A. Stone estate in Charlottesville, Virginia; and the French gardens at Sunken Orchard, on the Charles McCann estate in Oyster Bay—a project that won Flanders the 1932 Medal of Honor from the Architectural League of New York.

Flanders' practice was wholly devoted to designing gardens for the Social Register set, work that vaporized overnight with the Great Depression. Facing unemployment, Sprout pivoted to the public sector. She secured a job with the Division of Design of the New York City Parks Department, becoming one of scores of young men and women hired via the Architects Emergency Committee to staff a wholesale upgrade of New York's immense park system. They drafted plans on makeshift tables in the Arsenal garage, often working well into the night. Supervising were two men handpicked by Moses to streamline park design in the city: Gilmore Clarke and architect Aymar Embury II.

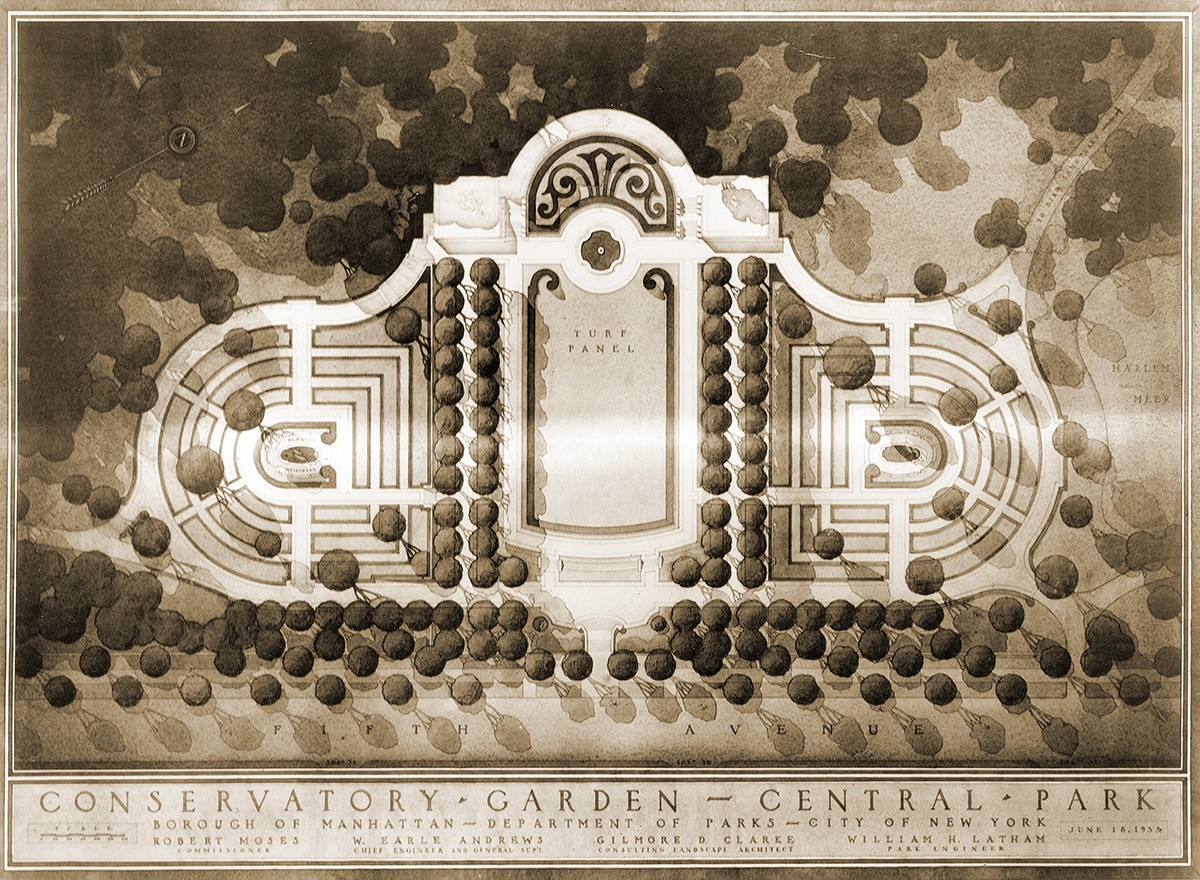

Clarke was quick to recognize Sprout's mastery of plant material and garden design and tapped her to work on two flagship projects—the Central Park Zoo and the Conservatory Garden. On the latter she teamed with Brazil-born Thomas Drees Price, who had excavated Horace's villa while a fellow at the American Academy in Rome. Sprout's facility with French garden design and Price's knowledge of Renaissance villas fused to produce a Franco-Italianate masterpiece—formal garden for the people. Over the next five years Sprout planted some of the highest profile parks in the city: City Hall Park; Bryant Park, Battery Park, Tompkins Square Park in the East Village; Borough Hall Park in Brooklyn; Joyce Kilmer and Henry Hudson parks in the Bronx. Her signature was a pair of hedges framing a central lawn panel, terminated in a circular or squared spiral.

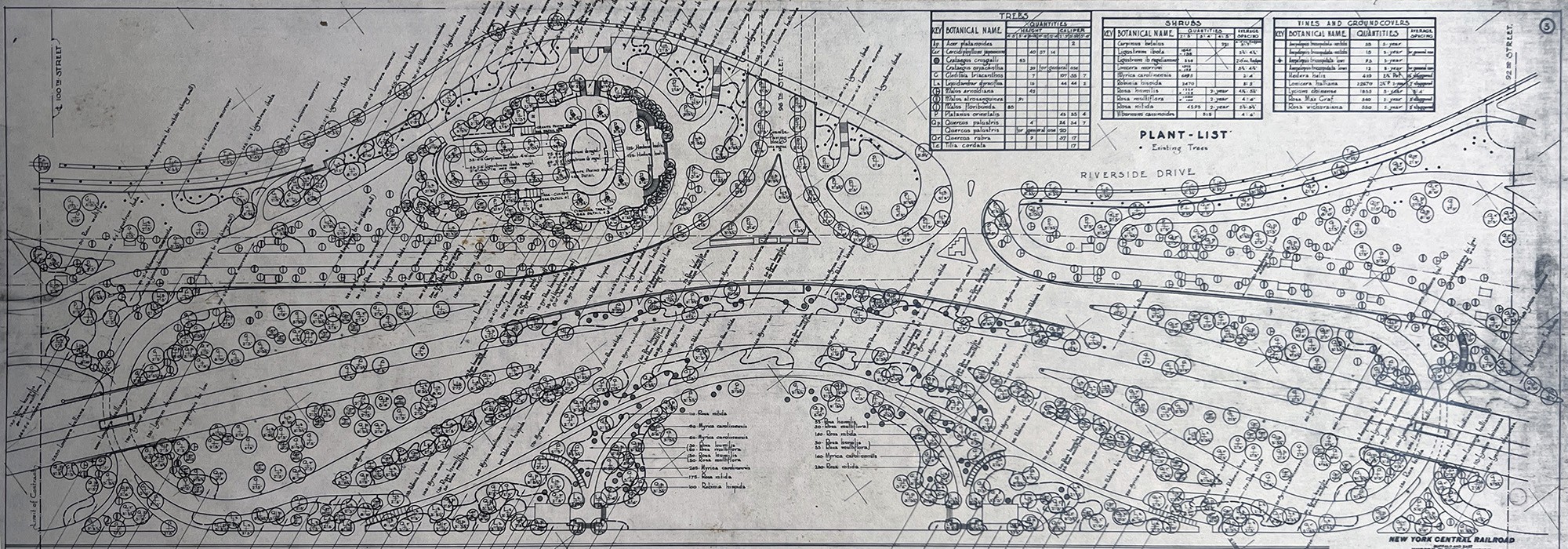

In 1935 Clarke and Rapuano began working on the West Side Improvement—a Moses super project that ran the Henry Hudson Parkway along the river, hid the New York Central tracks in an enormous vault, and expanded Olmsted's old Riverside Park into a New Deal playscape of promenades, pools and ballcourts. Sprout was charged with planting the entire thing. She set out floral beds and borders and thousands of flowering trees and shrubs, turning the massive infrastructure play into an urban oasis. Even crabby Lewis Mumford was impressed; he called Riverside Park "the finest single piece of large-scale planning the city can point to since the original development of Central Park."2 Clarke and Rapuano opened an office of their own in 1939—a "professional practice in all phases of the broad field of land planning."3 Sprout was their first hire and effective third partner. Her association with Clarke became personal too; having courted for several years, the two married in 1941. It was a progressive office in many ways, but not in terms of gender. In 1949, only eight out of 50 staff were female—all but Sprout secretaries or stenographers. But she was entrusted with enormous responsibility—directing planting design on every major project in the office—works that changed the face of New York City. Sprout would plant all four Metropolitan Life Insurance Company housing complexes that Clarke and Rapuano master planned—Parkchester, Stuyvesant Town, Peter Cooper Village, Riverton in Harlem, Parkfairfax in Virginia. She prepared planting plans for the Brooklyn Heights Promenade and Cadman Plaza Park, laid out gardens at the United Nations headquarters, and humanized—as best she could—the Van Wyck and Major Deegan expressways.

Sprout fully came into her own with the 1939 New York World's Fair, a marvel of the future built over a hellscape of cinders and trash in Flushing—the "biggest, costliest, most ambitious undertaking," gushed the Times, "ever attempted in the history of international expositions."4 Clarke and Rapuano prepared the site plan and ordered a planting program that would transform the reclaimed dump—"a barren waste assaulted by terrific dust storms"—into an oasis.5 More than 10,000 mature trees—some 12 inches in diameter and 80 feet tall—were sourced from farms and fields across the Northeast.

But the real showstoppers were closer to the ground. In a brilliant marketing ploy, the Holland Tulip Growers Association gifted the city 1.25 million tulip bulbs for the fair. To fair planners these were so many hot potatoes; what could possibly be done with them all? Sprout saved the day. Dusting off her French curves, she sketched out a dizzying array of planting beds, arranging the bulbs by height and color. She set thousands in scalloped beds along Constitution Mall—white tulips at the Trylon and Perisphere and increasing in hue and intensity to deep red at Rainbow Avenue. Scores of varieties were used—Zev, St. James, Clara Butt, Whistler, Grenadier, Arethusa, Zwanenburg, Rising Sun, Seafoam, Telescopium. Sprout configured other beds in the shape of waves, Aztec serpents, Greek keys and Vitruvian scrolls, a stylized Lady Liberty, an airplane propeller.

All these beds had to be excavated to a depth of seven inches, the bulbs spaced apart on a layer of sand then backfilled and underplanted with pansies. It was hazardous work. "Every tulip bulb had to be dipped in red lead and very carefully handled," Clarke noted, "because if one's fingers touched the bulb and took any of the red lead off, field mice would get in and destroy the plantings." Red lead, or lead oxide, is a toxic compound used for pigments and pyrotechnics. Bulbs were dampened with kerosene before being dusted with the powder, which dissuaded rodents but also poisoned the gardener. But the tulips were a showstopper, a highlight of the largest, most well-attended World's Fair in U.S. history (45 million people visited, equal to one out of three Americans at the time). The Herald Tribune called Sprout's work "the greatest sensation in the history of American horticulture."

Hers was a bright, brief career. A heavy smoker all her adult life, Mary Elizabeth Sprout was only 55 when she was felled by lung cancer. Would she be better known today had she survived? Possibly. But though Clarke and Rapuano were benefactors who helped make Sprout's career, her association with the powerhouse firm was a mixed blessing. It enabled her to shape some of the most famous spaces in America yet assured that her work would always be subsumed by the powerful men in whose orbit she labored.

Thomas J. Campanella is a professor of urban studies and city planning at Cornell University and Historian-in-Residence of the New York City Parks Department. His latest book, Designing the American Century: The Public Works Legacy of Clarke and Rapuano, will be published next year by Princeton University Press.

Bibliography

[1] Smith Alumnae Quarterly (February 1929), 258.

[2] Mumford, "Westward Ho!", The New Yorker (25 February, 1939).

[3] Letter from Gilmore D. Clarke to Michal Rapuano (n/d). Collection of Marga Rogers.

[4] Quoted in David Gelernter, 1939: The Lost World of the Fair (New York: The Free Press, 1995), 14.

[5] Richard Churchill, typewritten news release on fair planting program (n/d). New York World's Fair records, New York Public Library Archives and Manuscripts.