It Takes One: J. Patrick Manhart

In my early childhood, I lived in a variety of places from Nebraska and Louisiana to Kansas in the Dust Bowl era. At the time my visits to my grandfather’s farm in Iowa and another grandfather’s house located in the center of a small town in Colorado were the highlights of my life. The gardens at each made me yearn for a place where I could have my own garden. On my father’s return from contracts in the Middle East we settled down in a place that had a yard where I could garden.

I pursued a degree in botany in college, where my professor was an ecologist who was also a devoted painter. I assisted in helping her develop a landscape design course for the department. On graduating I was more interested in design than in botany. I pursued a master’s degree in landscape architecture, which included architecture and urban planning. After graduation I worked for a period as a city planner. This was followed by my own practice as a landscape architect where I worked for several decades on an Italian Renaissance garden. The garden had deteriorated since being given to the City as a museum. My work involved research into the original design intent and an assessment of its condition. Ultimately, my close association with work at museums later led me to exhibition design. As time passed, and I traveled, I developed a keen interest in the history of gardens and the factors that shaped them.

How would you define a cultural landscape?

The cultural landscape is the interaction between a unique environmental site and those that occupy it. Cultural differences and similarities are reflected in the way that each group adapts to their environment, both physically and spiritually. Likewise, the actions of each group impact the environment they are in. This is perhaps the most interesting aspect of studying cultural landscapes for me.

Why are you interested in/why did you get involved with the landscape at the Couse-Sharp Historic Site?

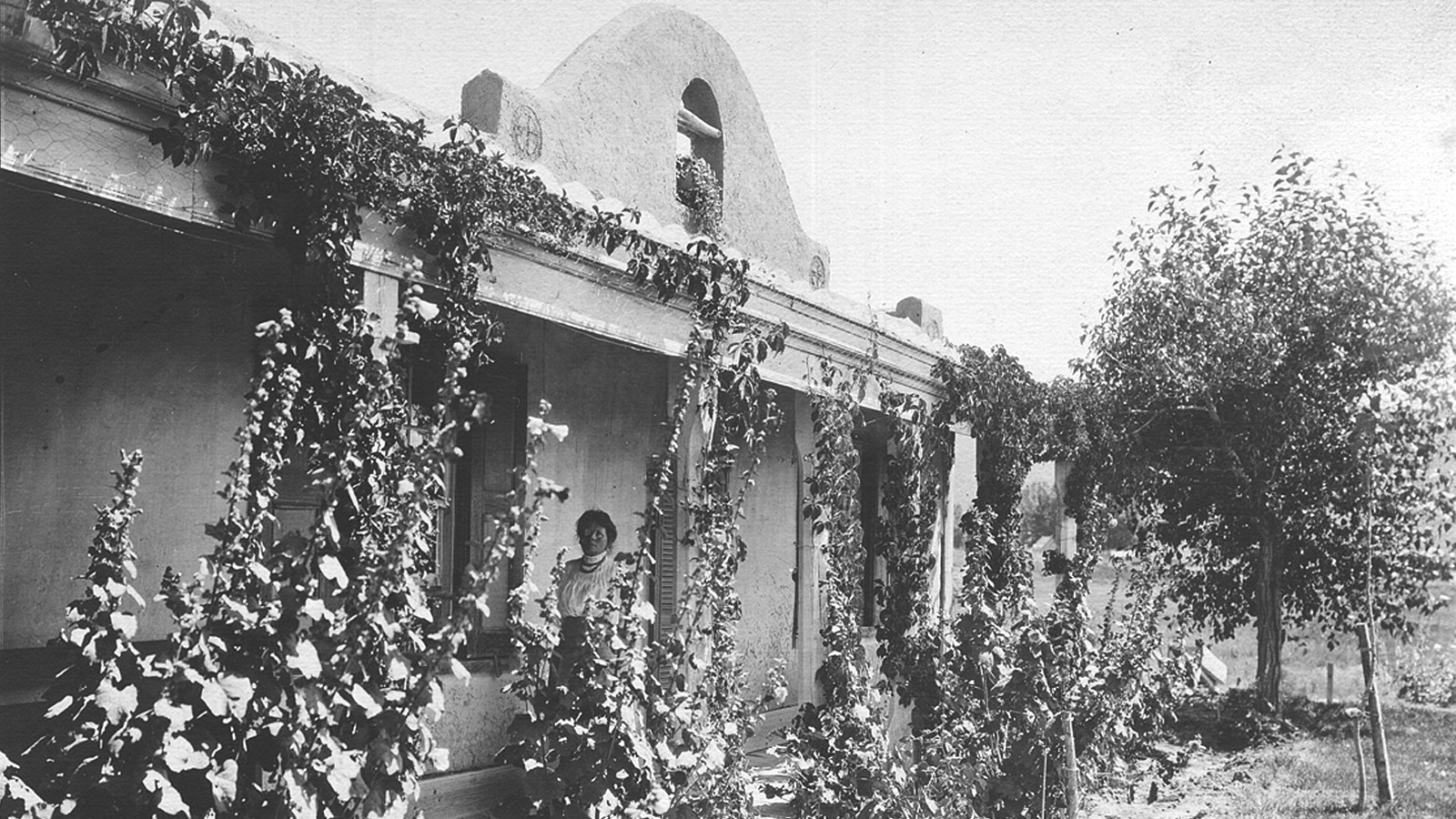

My interest in the garden stems from my first visit to Taos in 1950 to visit the painter Ila McAfee Turner. She lived at the outer edge of the two block urban development around Taos Plaza. Looking north from her picture window, the view was of fields and a few adobe houses. The Taos streets were largely unpaved and the town seemed little past the era of the Western Frontier. The architecture was largely Puebloan and Territorial style. It had the authentic feel of being a remnant of the culture from ages past, not as Disneyfied as Santa Fe was becoming. At the time, I was not aware of the garden at the rear of the Couse-Sharp Historic Site, the only landscaping I noticed were the hollyhocks around the edges of the building. After moving to Taos forty years later, I came to know the Couse property quite well and became friends with Eanger Irving Couse’s descendants. The Couse-Sharp Historic Site was astonishingly unchanged. As one of the few places in Taos that had not been materially altered in the ensuing forty years it seemed important to me that this example of Taos as it existed over a hundred years ago should be preserved and maintained for future generations. I felt that I would like to do anything I could to help protect this unique place.

How did your understanding of this landscape change as a result of your advocacy efforts/work?

Photographs of the area surrounding Taos just before or after the beginning of the Twentieth Century show a largely agrarian landscape centered on a small plaza with a small number of adobe structures extending outward for only a few blocks of development. Few, if any trees were present and the streets were unpaved. Water to sustain any plantings was provided by acequias (irrigation ditches). The surrounding grain fields and orchards were sustained in this way. There was little evidence of any gardening outside that cultivated for produce, although the acequia system had been long established by the preceding Native American and Hispanic settlements.

As more Picturesque gardens such as that at the Couse-Sharp Historic Site came to be developed, they were dependent on the help and knowledge of people familiar with the acequia system of irrigation. Virginia Walker Couse’s garden was seminal in instigating gardening in the Taos community, and members from the Taos Pueblo were instrumental in helping her create it. Plants and seeds from the garden were freely given throughout the community and the site later became known as the “Mother Garden of Taos.”

Did your understanding of other cultural landscapes change as well? If so how?

The development of the landscape in colonial New England had something in common with that in the Taos area. Anglo (European) emigrants who came to the New England shores encountered a long established Native American culture whose valuable knowledge enabled them to adapt to their environment. What was different was that in the Northeast the climate and environment were more similar to the one that the emigrants had left behind. In the Southwest, the necessity of relying largely on irrigation to maintain the landscape produced a distinctly different system of garden development. The abundance of water allowed for the early development of industry in the Northeast, significantly changing the landscape from that day forward. The advent of industry in the Southwest awaited the development of the railroads and the scarcity of water has had a limiting affect on development of industry. Ranching and farming still largely shape the landscape in the Taos Valley.

What is the message that you would like to give our readers that may inspire them to make a difference?

Every effort should be made to preserve and maintain the landscapes we inherit and the original systems of maintaining them. Once these are lost it is difficult or impossible to reinstate this cultural heritage. In Taos, the acequias which were constructed to provide water to the City’s landscape are no longer functioning. The failure to keep the system going forces residents to use expensive and limited municipal water from wells that deplete the aquifer. At the same time runoff from the mountains that feed the acequias isn’t being utilized as it might be. Water considerations are a key factor in maintaining our precious inherited landscape.