It Takes One: Mary Millman

Over the past several decades I've been a teacher, an author, a lawyer, a businessperson, and a civil and human rights activist. I have a couple of academic degrees from the University of California at Berkeley, and consider the best part of my law school experience an eye-opening internship with Equal Rights Advocates. These days I am working on a new venture—San Francisco 's Antique and Artisan Market at United Nations Plaza. I am trying to infuse this unique outdoor covered market with the new spirit of care and diversity now emerging in San Francisco.

In pursuit of my lifelong interest in California's art, culture, and history I've often settled on projects that address quality of life issues in various contexts. In furtherance of the struggle for civil rights in the American south in the 1960s I taught first at Miles College and next at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. As a children's advocate in the 1970s I co-founded and managed the first childcare information and referral service in the United States, a model for the future. Also in the 1970s while in law school, I served as contracts and copyright advisor to the California Arts Council, then newly reinstituted by Governor Jerry Brown. All through this period and later, with Western photographer and author, Dave Bohn, I edited or authored six volumes of Western history including a catalog raisonne and artistic biography of John William Winkler, San Francisco 's famous etcher. After more than a decade of private law practice in downtown San Francisco, I wanted to return to hands-on organizing and, bluntly, to the real world. That's roughly how I found myself involved with United Nations Plaza.

How would you define a cultural landscape?

A cultural landscape is a physical construct, produced by people, the design, materials, and function of which express or define the historic, social and political character of a geographic area in a certain period of time. This panorama captures the essence and textures that made the time and place unique.

Why did you get involved in the landscape that was threatened in your community?

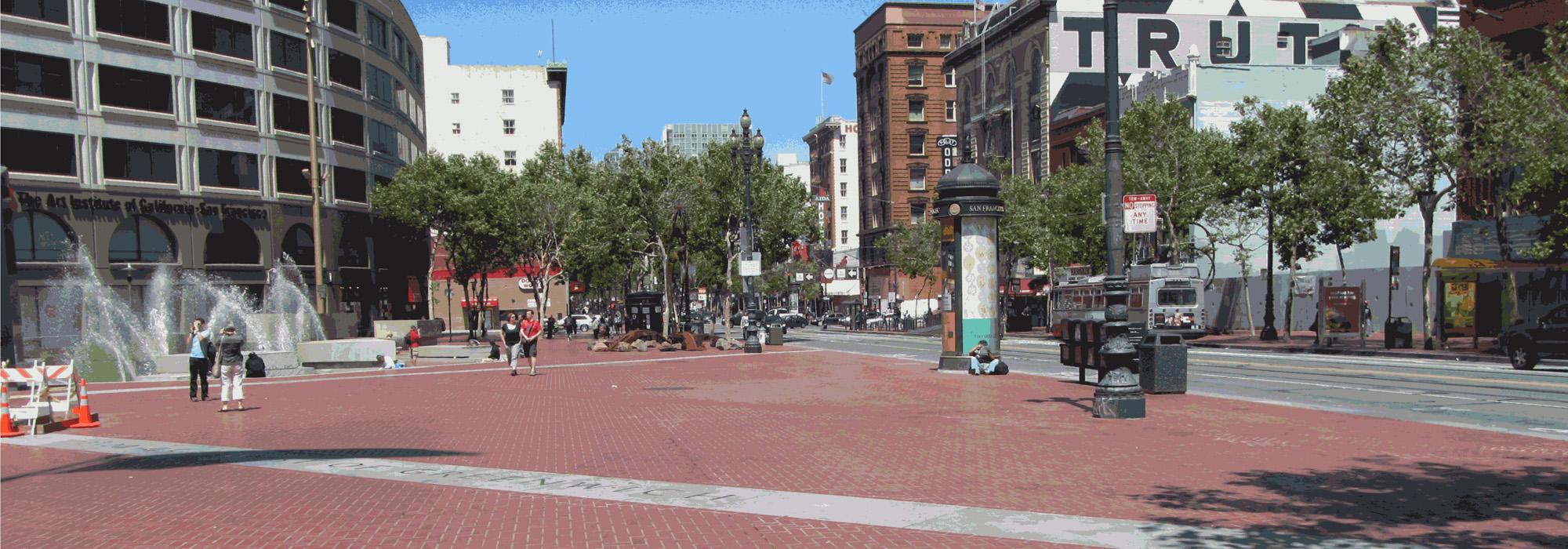

My involvement with United Nations Plaza began when a significant handful of San Francisco citizens inquired whether I would consider opening an outdoor market in the Plaza. Since I regarded the Plaza as an outstanding location for a market I jumped at the opportunity. However by 1999 when the precursor to San Francisco 's Antique and Artisan Market opened, UN Plaza at the eastern margin of San Francisco 's Beaux Arts Civic Center had become the very symbol of wholesale failure meaningfully to address the cognate problems of homelessness, narcotic addiction and substance abuse, and endemic, ever-increasing violent criminality. The Plaza itself had been created in the 1950s by bricking in two blocks of Fulton Street and installing at the west end a commemorative colonnade and at the east end, Lawrence Halprin's fountain. Much of UN Plaza's 2.3 acres were left bare in contemplation of heavy foot traffic to Civic Center and rapid transit stations. The location of the Plaza had always been considered the "front door" to San Francisco Civic Center. By the late 1990s though, conditions were so bad that no one would think of walking through it.

Civic desperation about the situation reached such a level that one city agency proposed spending a million dollar federal grant earmarked for "pedestrian improvements" to revive Fulton Street and thus obliterate the Plaza altogether. Besides removing the historic United Nations columns, this plan would have made it impossible to conduct the Antique and Artisan Market, and would also have displaced one of California's earliest and most valuable organic farmers' markets that has used the Plaza two days a week for more than 20 years. Thanks to the sponsorship of my district supervisor, I was placed on the committee to oversee the expenditure of the grant and report back to the Board of Supervisors.

Because of a general outcry at the proposal to dismantle an historic Plaza, a second—and eventually eight more—sets of plans were brought forth. In all of these the colonnade was restored, but the full brunt of the landscape architect's wrath descended on Lawrence Halprin's fountain which was to be replaced by a taxi stand at the edge of yet another road that would be paved with slabs cut from the fountain's magnificent Sierra granite blocks!

As the committee's work progressed, it became clear that the group would approve the removal of the fountain. It fell to the few dissenters to convince the Board of Supervisors that this drastic solution would not solve any social problems and would deprive Civic Center of an outstanding asset. We decided to advocate for the best outcome rather than just fighting plans that would result in the worst outcome. Our attitude of positive change brought victory at every governmental level we addressed. We blocked all attempts to destroy Mr. Halprin's fountain. In this activity, we discovered more friends of the preservationist point of view than we could ever have imagined.

How did your understanding of this landscape change as a result of your advocacy efforts?

My own understanding of the cultural landscape of United Nations Plaza has not changed very much, but saving the fountain was a pivotal factor in the reversal of the condition of the area. Although the continuous conduct of the markets has contributed greatly to the day to day work of social reclamation, Mr. Halprin's fountain has become a symbol of the future of the area.

Did the understanding of others change as well? If so, how?

For a time after destruction of the fountain was defeated, a city agency placed a chain link fence around the fountain, then cement-filled buckets with garish yellow plastic chains. These unsightly barriers were installed to keep people out of a fountain that was built specifically to invite people in!

This past June was the 60th anniversary of the signing of the UN Charter, and as part of the celebration, San Francisco was selected to present World Environment Day. Reflecting the new spirit in U N Plaza, Mayor Gavin Newsom directed all barriers around the fountain removed and to this date they have not returned. The fountain has been restored to its original state and many, many downtown citizens may be seen sitting at its edges or approaching the tides on its floor, including street people who now respect the fountain and use it as others do.

There is a kind of pleasant irony in this outcome. Although destruction of the fountain would have done nothing to improve or ameliorate the many problems of the Plaza, saving the fountain has added a new spirit and contributed quite a bit to the restoration of civility.

What is the message that you would like to give our readers that may inspire them to make a difference?

"It takes one" is the first of two linked messages.

One person can have a vision, take a stand, write an article, give a speech, and create a beginning.

Something important happens though when others join together and take up the challenge of change. Success is achieved by the transformative power of many people working in concert.

In San Francisco we celebrate each one and what each one has contributed to the success we experience today in United Nations Plaza.