Stewart E. King Biography

A mentor and role model to other professionals, King worked tirelessly to secure the landscape architectural registration law in Texas.

Stewart Edmund King was born in Boerne, Texas, on August 7, 1907. He received a Bachelor of Science degree in Landscape Architecture from Texas A & M University in 1931. King began his career as a landscape architect in 1931 with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, working on a planting project at Randolph Field in San Antonio. He then worked as a landscape architect for Baker-Potts Nursery in Harlingen, Texas, after which he filled a similar position with the Civil Works Administration. King was employed by the National Park Service from 1934 to 1939. During his employment with the Civil Works Administration and the National Park Service, he spent considerable time working on historic sites.

King was director of the San Antonio Parks and Recreation Department from 1939 to 1951, where he devoted his enthusiasm and abilities to developing many of the facilities enjoyed today by both residents and visitors. He assisted in restoring the historic “La Villita” area in downtown San Antonio, and was active in the preservation of the urban San Antonio River. King often used indigenous plants in his palette. Along with Charles Whall, he conducted pioneering work in large tree-moving, initially at La Villita and the River Walk, working with native oaks and cedar elms.

King was ahead of his time in environmental consciousness, including the preservation of urban open spaces and park lands. In his article “The Vanishing Green,” drafted circa 1961,he calls professionals and enthusiasts to action against “the vanishing green of trees, lawns and wooded areas in parks and open spaces being brought about by the hurly-burly growth of our metropolitan cities.” He goes on to point out that “park commissions and administrators of cities are frequently faced with the potential loss of park and recreation land for camouflaged commercial gain or projects proposed in the ‘interest of public welfare’.”

As exemplified in this article, King’s passionate stewardship and leadership helped garner considerable attention from the Texas Department of Transportation and the state legislature regarding the potential impact of the routing of highways through park lands and urban open spaces.

From 1951 until his death, King enjoyed a varied private practice with offices in the historic King William area of San Antonio. He shared office space with architect O’Neil Ford and city planner Sam Zisman. While maintaining autonomous practices, they collaborated on larger projects such as Trinity University and Texas Instruments Headquarters, where they integrated architecture, landscape architecture, and planning.

King won recognition and awards on many of his projects including Kleberg Park, developments on the King Ranch (no relation), Intercontinental Motors, Victoria Plaza, and early U.S. Army Corps of Engineers recreation facilities at Canyon Lake. His design work, including the Harry Evons and Marshall Steves residences, La Villita Assembly Hall and the Austin Town Lake development, was featured in national publications. Stewart served as landscape/site planning consultant to San Antonio’s Southwest Research Institute, Housing Authority, Botanical Center, and to S. B. Zisman, Planning Consultant of San Antonio.

King joint-ventured with his protégé, James E. Keeter, as the landscape architects for all public spaces and several private exhibitions for Hemisfair ‘68, as they occasionally did later on other large-scale projects. One King & Keeler project that today we would term “sustainability based” was a master plan for the White Sands Missile Range cantonment area, with the primary objective of water conservation. They produced a permitted index of water-conserving indigenous plants and proposed capturing sewage effluent, cleansing it through filtration ponds, and using it for irrigation of an existing golf course. The entire project plan received accolades by the Corps of Engineers, but the plan was not completed as originally designed.

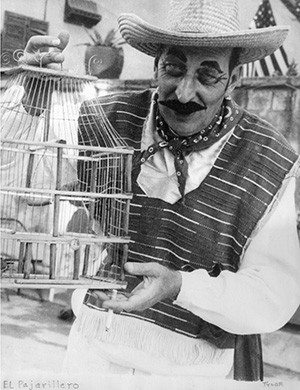

Stewart as 'Pedro the Bird Man", El Pajarillero, at celebrations in San Antonio.Stewart’s deep interest and concern for historic preservation led to his involvement with the San Antonio Conservation Society and, as advisor and consultant, the Archdiocese of San Antonio’s committee for preservation and restoration of the Old Spanish Missions. He was well-known for his role as “Pedro the Bird Man,” which he assumed for the annual festive Night in Old San Antonio. For this event Stewart drove to Mexico, bought wooden bird cages and parakeets, and, in disguise, sold them during the festival, giving the proceeds to the Conservation Society.

King contributed considerable effort toward securing the landscape architectural registration law in Texas, while encouraging younger people in his profession. He was a Fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects, serving on many of the organization’s committees from chapter to national level. In addition, he was a trustee for the Southwest Chapter. Other professional affiliations included membership in the American Park and Recreation Society, of which he was also a Fellow, and the National Association of Housing and Development Officials.

Throughout his career, King was a mentor and role model to other professionals. Peer landscape architects fortunate to have been associates sequentially included William C. Belcher, James E. Keeter, Charles W. Greiner, W. Eugene Griffin, and the author. On August 7, 1970, Stewart E. King succumbed to cancer at the age of 63.

Bibliography

A Resolution of the Texas State Legislature honoring Stewart E. King, sponsored by The Honorable Jake Johnson, Representative of Bexar County, 1970.

George, Carolyn. “O’Neil Ford, architect,” Texas A & M University Press, 1992.

Dillon, David. “The Architecture of O’Neil Ford, Celebrating Place,” University of Texas Press, 1999.

Images courtesy the author.

About the Author

Glenn Cook, FASLA, is an associate professor of landscape architecture at Mississippi State University. At King’s invitation, Cook continued the practice left by Stewart in 1970 until joining the landscape architecture faculty at Mississippi State University in 1978.