Takeo Uesugi Biography

Takeo Uesugi (1940-2016) was born in Osaka, Japan, on March 25, 1940, the son of Reverend Seichi and Kiku Uesugi and the youngest of their five children. His early years were filled with the hardships of post-War Japan, but his father’s spiritual devotion and his family’s support put him on a path to practicing landscape architecture and missionary work in the United States. In 1962, Uesugi earned a B.S. at the University of Osaka Prefecture under the guidance of Professor Tadashi Kubo. He then undertook graduate studies in landscape architecture in the Department of Forestry at Kyoto University, where his professors included both Akira Okazaki and Dr. Makoto Nakamura. He was thus the fourteenth generation of uekiya (Japanese garden craftsmen) in his family, and following his father, he also became a second-generation head minister of the Tenrikyo Church.

Uesugi arrived in the United States in 1965 and received an M.L.A. at UC Berkeley in 1967, where he studied closely with his mentor Garrett Eckbo. Uesugi thus became well versed both in the traditional garden design principles set forth in the Sakuteiki, an eleventh-century Japanese landscape design classic, and in the tenets of Western landscape architecture. He was intrigued by the Modernist design movement and was inspired by pioneers such as Isamu Noguchi, whose innovative and bold forms impacted all aspects of environmental design. Uesugi was also exposed to Modernist sensibilities by working with notable landscape architects such as Lawrence Halprin and the firm Royston, Hanamoto, Beck & Abbey, between 1966 and 1967; but it was his internship from August through December 1967 at the office of M. Paul Friedberg and Associates (now MPFP Landscape Architecture and Urban Design) in New York City that most shaped his design philosophy.

In December 1967, Uesugi returned to Japan to design the landscape of the Japan Pavilion for the Japan World Exposition of 1970, to take place in Osaka. The architectural firm Nikken Sekkei was contracted to build this signature piece for the exposition, and Uesugi was asked to serve as a key design consultant. He invited landscape architect Robert Murase, who was in Kyoto at the time, to join him on the design team. Both men were interested in contemporary Japanese landscapes and viewed the project as an opportunity to create a model for future design in Japan. It was during this time that Uesugi began to synthesize Modernist sensibilities with the aesthetics of Japanese gardens. The result was rustic and tranquil spaces marked by refined simplicity and asymmetric balance, and that responded to local topography and climatic conditions.

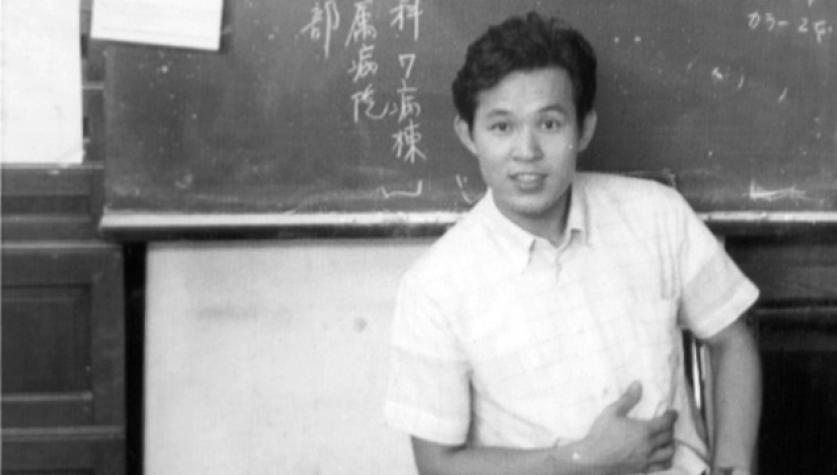

While in Japan, Uesugi was hired to teach landscape architecture at Kyoto University, where he met his future wife, Hiroko, whom he married in 1969. The Japan Pavilion was completed in 1970, and Uesugi returned to the United States later that year to become a full-time faculty member in landscape architecture at the California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, where he would teach for over thirty years.

In 1971, he established Takeo Uesugi & Associates (TUA), a private practice in California. This provided him with the opportunity to conceptualize and create landscapes that sensitively addressed environmental factors and that were visually striking and spatially balanced. At the core of his design philosophy was the idea that principles of Japanese garden design could promote sustainable practices and could be applied in any region around the world. Furthermore, he believed that the inspiration for a design should be drawn from the site itself, through the study of its natural and cultural history.

One of Uesugi’s first notable public projects came in 1980 with the James Irvine Garden at the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center (JACCC) in Los Angeles. The garden worked in harmony with the sloping topography of the site and drew much of its inspiration from the JACCC’s mission to promote Japanese and Japanese American arts and culture. The multigenerational experiences of Japanese Americans are symbolically represented by the use of water throughout the garden, from a dynamic waterfall reflecting the spirit of Japanese immigrants, to a stream that splits and finally converges, representing the plight of many second-generation Japanese Americans interned in camps during World War II. In 2007, TUA renovated the garden to support new programming, including an amphitheater and a transitional plaza.

Uesugi also developed ways to integrate Japanese aesthetic sensibilities with contemporary commercial spaces across the nation, such as the San Diego Tech Center in 1984; the Grand Hyatt Atlanta in 1990; and the Bannockburn Plaza Business Park in Chicago in 1990. These commercial projects used principles of Japanese garden design to enhance the aesthetics and the functionality of high-traffic areas. The San Diego Tech Center landscape, for example, comprises pleasant pathways that weave through a series of outdoor rooms, encouraging employees and guests to use the outdoor spaces during breaks and visits. Uesugi also completed the Philip Brett Memorial Peace Garden at UC Riverside in 2007; the Japanese Friendship Garden in San Diego’s Balboa Park in 2015; the Mobile (Alabama) Japanese Garden (an ongoing project); and the Huntington Library and Botanic Gardens in San Marino, California, in 2012, which included developing a master plan for the historic Japanese garden and its expansion.

In 1981, Uesugi received his Ph.D. in landscape architecture from Kyoto University, where he had completed coursework years earlier. That same year, the American Association of Nurserymen awarded the James Irvine Garden its National Landscape Award, which was bestowed by First Lady Nancy Reagan during a ceremony at the White House. Uesugi became a Fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects in 2001, and he received a lifetime achievement award at the International Conference on Japanese Gardens Outside of Japan in 2009. He was also awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure from the Japanese government in 2010.

After Uesugi’s retirement, his practice was maintained by his youngest son, Keiji, who is also a landscape architect. Uesugi lived with Hiroko, his wife of over forty-five years, in West Covina, California. He passed away on January 26, 2016, after a battle with cancer.