We Need a Broader Vision for Visionary Postwar Developments

New York’s Battery Park City and Washington, D.C.’s Pennsylvania Avenue between the U.S. Capitol and the White House, America’s Main Street, are two examples of ambitious, civic-minded urban planning that employed landscape architects, architects and allied professionals in the creation of contiguous projects. Moreover, they are significant works of modern and postmodern landscape design. Another characteristic the two share is that they are collections of individual projects that have separate identities, but are also part of larger, symphonic narratives. Lastly, they both have sites that are under threat.

Landscape architecture at this scale does not happen in a vacuum; it requires the leadership of strong patrons – in these instances, Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation (PADC) and the Battery Park City Authority (BPCA).

The genesis of efforts in Washington, D.C. began in 1961 when President John F. Kennedy created the President’s Commission on Pennsylvania Avenue, which was ultimately followed by the creation of the PADC a decade later. The PADC commissioned major practitioners including Dan Kiley, Hideo Sasaki, M. Paul Friedberg, Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, George Patton, Carol Johnson, Wolfgang Oehme and James van Sweden to create a contiguous collection of parks and open spaces that stretched 1.2-miles in length. It was a unique and pioneering effort for all of these practitioners, particularly the landscape architects, to work alongside each other.

Today, these parks and open spaces fall within the Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Site and are maintained by the National Park Service (NPS). Over time, in-depth site documentation and scholarly analysis has been undertaken to assess the historic significance of this ensemble of cultural landscapes. In 1965, the Avenue was listed in the National Register of Historic Places, with what’s called a “period of significance” starting in 1791. Subsequent NPS-commissioned Cultural Landscape Inventories, the most recent issued May 10, 2016, and covering the period 1976-1990, have certified the importance of the Avenue. Moreover, the Friedberg-designed Pershing Park, arguably the jewel in the crown of this collection, has been determined eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, a designation usually applied to sites that are at least 50 years old – Pershing opened in 1981.

Pershing, as I’ve written before, has been selected as the site of a national World War I Memorial. The initial proposed design essentially called for the eradication of Friedberg’s creation, a park-plaza with a waterfall and pool as its focal point and a planting plan by Oehme van Sweden. New construction in the so-called Monumental Core of the nation’s capital requires approvals from numerous agencies, most notably the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA). The significance of Pershing being determined National Register eligible is that efforts are required to mitigate adverse effects to the park. The CFA recently approved a design concept for the new WWI Memorial, but threats to its central pool and plaza remain – its basin would be reduced in scale and disconnected from its cascading water source, and a 65-foot-long bas-relief bronze sculptural wall that is still too long for the space would be inserted, fundamentally altering the visual and spatial qualities of the park.

Battery Park City, by contrast, is a very different animal; it was created on landfill built off of the lower west side of Manhattan. The Battery Park City Authority (BPCA), established in 1968, “is a New York State public benefit corporation whose mission is to plan, create, coordinate and maintain a balanced community of commercial, residential, retail, and park space within its designated 92-acre site,” according to its website.

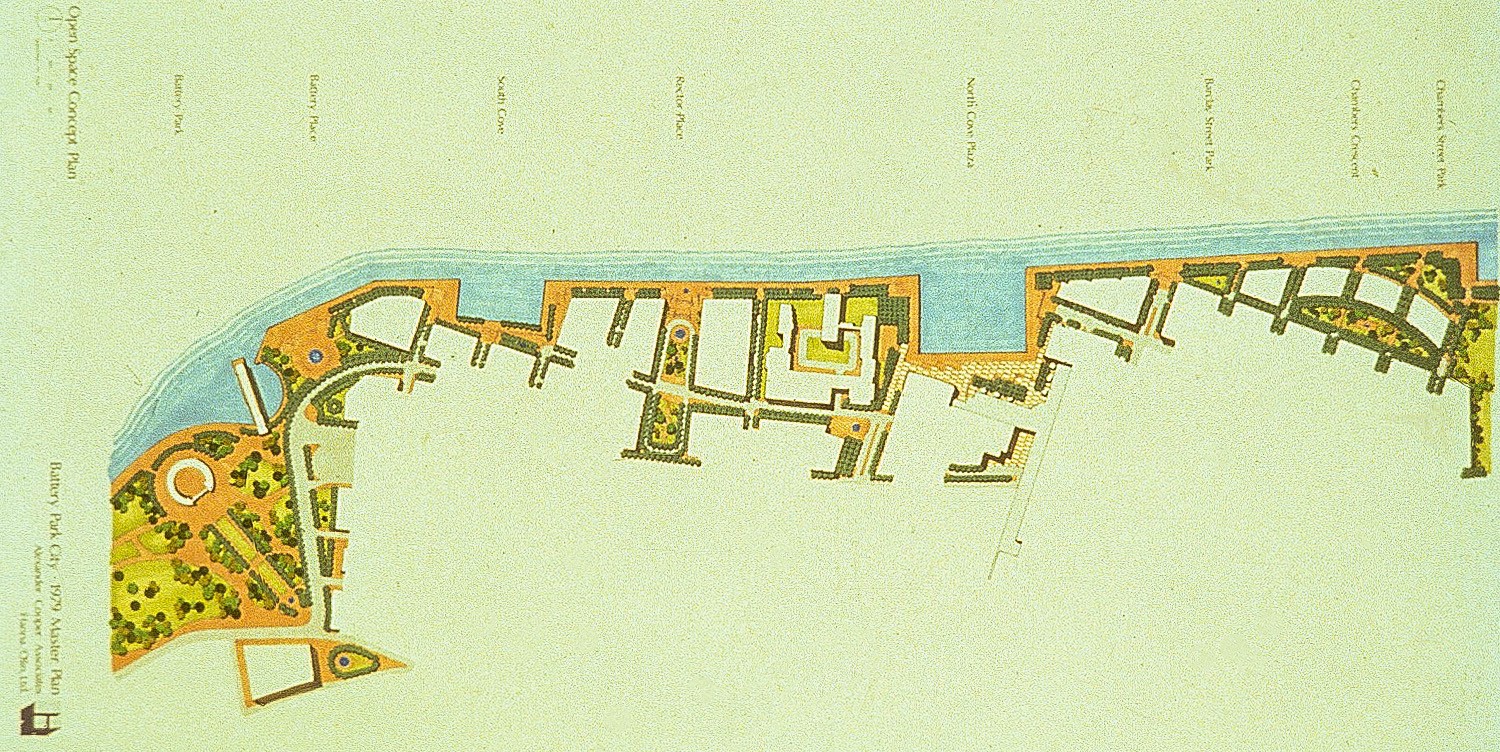

In 1979, Cooper Eckstut (as lead planners) with Hanna/Olin as landscape architects (Laurie Olin lead) prepared a masterplan. It was revolutionary and influential for its time, and resulted in 26 parcels each designed independently by different developers. This continuous and contiguous neighborhood fabric emulated the city’s mixed character and design leadership. This unrivaled collection includes Rector Park, designed by Innocenti and Webel in 1985; South Cove, a collaboration with artist Mary Miss, Child Associates (with Susan Child and Doug Reed) and Stan Eckstut, opened in 1988; Nelson Rockefeller Park, by Carr, Lynch, Hack and Sandell with Oehme van Sweden as landscape architects; and the Esplanade, opened in stages by Hanna/Olin in the 1980s and 1990s. Olin’s Robert F. Wagner Park, Jr. opened in 1996, and Teardrop Park, designed by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, debuted in 2004. In 1998 architect Cesar Pelli’s World Financial Center was completed, with a Winter Garden and waterfront plaza by M. Paul Friedberg + Partners (it was restored in 2002 by Balmori Associates).

Unlike the high level of scholarship around Pennsylvania Avenue, which is essential in informing stewardship decisions, there is not a similarly comprehensive research foundation underpinning decision making at Battery Park City, as evidenced by current proposals that put the 3.5-acre Robert F. Wagner, Jr. Park at risk. The collaboration of Laurie Olin (with Hanna/Olin), horticulturist Lynden Miller, and architects Machado and Silvetti Associates resulted in a significant work of postmodern design. This park is simultaneously a gateway to Battery Park City and an exclamation point at its end.

[In the video below, a portion of a video oral history with landscape architect Laurie Olin, Olin discusses the creation of Robert F. Wagner, Jr. Park]