feature

An Aspirational and Inspirational Inaugural Race and Space Conversation

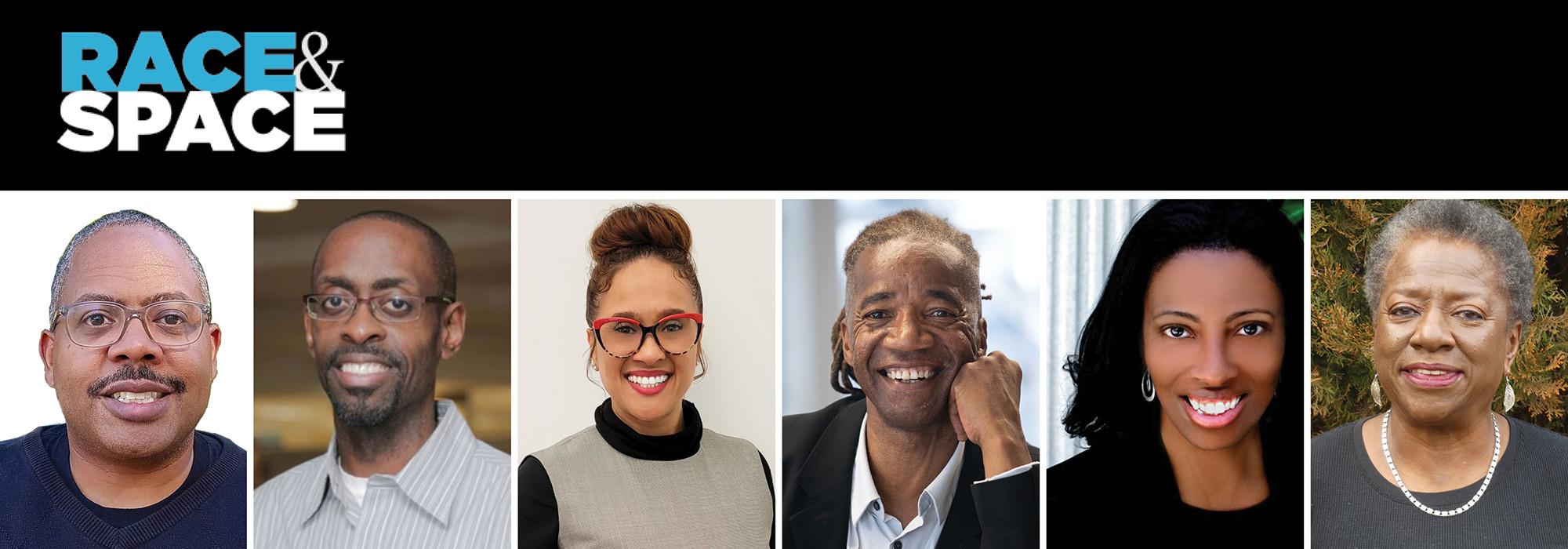

The Cultural Landscape Foundation’s (TCLF) inaugural Race and Space Conversation began with a bold declaration by event moderator April De Simone that was equally aspirational and inspirational; the conversation, she said, was about “more than race; it’s about the spatial practice of democracy.” As De Simone observed at the close, it has been “400 plus years in the making for conversations like this and it’s hard to cover in an hour and a half.”