The Battle of Blair Mountain Is Still Being Waged

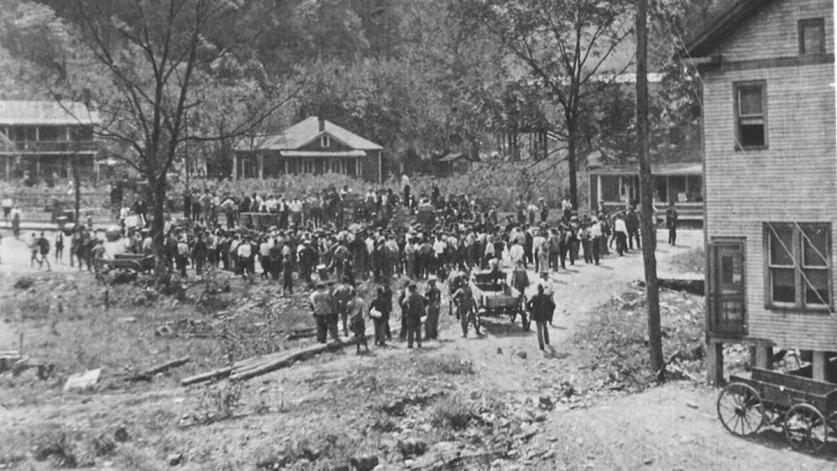

Carrying rifles and wearing red bandanas around their necks (further cementing the term “redneck” in the American vernacular), some 10,000 coal miners marched toward Mingo County, West Virginia, in August 1921, determined to put an end to the Mine Guard System and free their brethren who had been jailed under martial law. Blocking their path were the entrenched forces of local sheriff Don Chafin, dug-in with machine-gun turrets guarding key passes through the steep terrain. After days of fighting, which included bombs dropped from biplanes, the Battle of Blair Mountain ended when federal troops were dispatched. The Blair Mountain Battlefield, an important historical site that commemorates the fight for constitutional rights, and an archaeological trove of trenches, artifacts, and quite possibly human remains, could now be utterly destroyed by surface mining or timbering.

History

The largest armed uprising in American history since the Civil War, the Battle of Blair Mountain was the culminating event of the West Virginia Mine Wars, a series of conflicts between miners and coal operators spanning nearly a decade. In August 1921, an estimated 10,000 armed coal miners marched south from the state capitol at Charleston, West Virginia, towards the anti-union counties of Logan, Mingo, and McDowell. Their intent was to end the notorious Mine Guard System, which enabled the coal companies, backed by a private force of armed guards, to rule the coalfields as a police state in which the right to free speech, assembly, and other basic rights were forfeited as a condition of employment.

Eight in ten West Virginia miners then lived in unincorporated “company towns” without elected officials or independent police forces. Mine guards (nominally employed by the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency) maintained order, installing machine-gun turrets and searchlights to help quell any rebellion. The miners and their families rented company houses—one-room hovels, always within walking distance of the mine; were paid in company currency called “script”; and bought goods at company stores with set prices. Company representatives even controlled the mail, often removing what they considered to be “subversive” (pro-union) literature.

As the miners marched south in late August, company forces, deputized and led by Logan County Sheriff Don Chafin, set up ten miles of defensive positions north of the town of Logan along ridgelines stretching from Blair Mountain northwards to Mill Creek. The battle continued for four days before federal troops intervened and the miners, unwilling to fight U.S. soldiers, laid down their arms. In the aftermath, over 500 miners and their union leadership were arrested and charged with treason and murder. The battle has been called “Labor's Gettysburg” because of its significance to the history of unions and workers’ rights.

The battlefield covers nearly 1,700 acres and is heavily forested with steep slopes. Along ridgelines and at various strategic points, numerous defensive entrenchments, earthworks, and foxholes can be found. Bullet shell casings and buried guns are among the most common artifacts found on the battlefield, and some human remains may be buried there as well.

The Battle of Blair Mountain was perhaps the most forceful challenge to corporate power in American history, and the battle stands as a prime example of the sacrifices workers made and the struggles they faced in order to achieve union rights, benefits, living wages, safe working conditions, and pensions. It would take more than a decade after the battle for many of the miners’ objectives to be enshrined in law, but all workers in America now benefit from this early-twentieth-century struggle for workers' rights. Looking back today on the events of 1921, Cecil E. Roberts, the president of the United Mine Workers of America, sums up their significance this way:

Blair Mountain stands as a pivotal event in American history, where working men and women stood up to the lawless coal barons of the early twentieth century and their private armies and fought for their rights as Americans—and indeed, the rights of working families all over the world. It is a place where we can all be reminded that workers in this nation were literally forced to fight for their rights, and that those rights must constantly be defended or they will be lost. Blair Mountain is a beacon for all those who support American ideals of democracy, fairness, and freedom, which is what the miners were fighting for.

On a regional level, the conflict helped foster Appalachian stereotypes relating to "hillbillies" and "rednecks." The mainstream media of its day and the powerful corporate interests blamed the violence on the backward, mountain culture of the miners, promoting an historical narrative that has shaped the way Americans view Appalachians and how Appalachians view themselves.

Threat

The threat to the historical battlefield has long been recognized. In 2006, the National Trust for Historic Preservation included the site on its list of “America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places.” On March 30, 2009, the Blair Mountain Battlefield, covering 1,669 acres, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places for its importance to labor history, social history, and politics, with 1921 as the period of significance. Soon after the listing, coal companies that held permits to mine the area sued West Virginia state officials who had supported the nomination. The companies also formally appealed the decision to list the battlefield in the National Register, and within nine months of having been listed in the Register, the site was delisted.

In September 2010, several groups, including the Sierra Club and the newly formed Friends of Blair Mountain (FOBM), filed a lawsuit challenging the delisting. U.S. District Court Judge Reggie B. Walton vacated the delisting on April 11, 2016, declaring it to be in violation of federal law. He then referred the matter back to the Keeper of the National Register, who is now deciding whether to relist the site.

There are currently three surface-mining permits that overlap onto the battlefield. Two of the permits are through Arch Coal (Bumbo No. 2 and Adkins Fork) and one is through Alpha Natural Resources (Camp Branch). To date, preservation efforts have kept these mining projects at bay. Because the archaeological resources are less than a century old, most of the artifacts and earthworks associated with the battle are found on the surface or within inches of it. This means that timbering also has an adverse impact on the battlefield. Timbering disturbances have been documented on the Camp Branch Permit, destroying areas of historical significance in 2009 and 2011. Currently, there are no active timber operations on the battlefield, but there are no legal protections for the site concerning timbering.

Much depends upon the forthcoming decision of the Keeper of the National Register. If the decision is for the battlefield to remain delisted, then Arch Coal may proceed with attempting to surface mine the Adkins Fork Permit. If the Keeper rules to relist the battlefield, then the West Virginia Division of Environmental Protection will be further empowered to block certain mining permits, and there will be more time to work toward a permanent solution for the site.

How You Can Help

There has never been a complete archaeological survey of the battlefield. The West Virginia Mine Wars Museum is raising funds to sponsor a LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) scan of the Nomination Area in order to identify the major zones of historical significance and promote the site’s value as a potential historical park. Identifying specific areas of significance and promoting the interpretation of the site will put public pressure on landowners to refrain from mining or timbering the battlefield. The museum is also working to create an educational program for West Virginia public schools to help ensure future stewardship of the site, whose history is not currently included in the curriculum. Preparing a detailed report on the battlefield's economic potential as a heritage-tourism destination is also an objective, one in harmony with recent efforts of West Virginia Governor Jim Justice to promote tourism as a way to rejuvenate the state's economy.

Donate to the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum to help create educational programs and sponsor a LiDAR scan of the battlefield.

Contact the following officials and ask them to help protect the Blair Mountain Battlefield, a nationally significant landscape that should never be forgotten.

Governor Jim Justice (e-mail)

Office of the Governor

State Capitol, 1900 Kanawha Blvd. E

Charleston, WV 25305

Office Telephone: (304)-558-2000 or 1-888-438-2731

Governor's Mansion: (304)-558-3588

State Senator Richard Ojeda (representing Logan County, West Virginia; e-mail)

Room 213W, Building 1

State Capitol Complex

Charleston, WV 25305

Office Telephone: (304)-357-7857

U.S. Senator Joe Manchin (e-mail)

306 Hart Senate Office Building

Washington D.C. 20510

Office Telephone: (202)-224-3954

U.S. Senator Shelley Moore Capito (e-mail)

172 Russell Senate Office Building

Washington, DC 20510

Office Telephone: (202)-224-6472

Charles B. Keeney, Ph.D., is a history professor, author, and the vice president of Friends of Blair Mountain. A founding member of the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum, he is also the great-grandson of Frank Keeney, a central figure in the West Virginia Mine Wars who was charged with treason after the Battle of Blair Mountain.